The city spent millions to grow one anti-violence nonprofit. Instead, it nearly imploded.

NOMO received more than $6 million in public funds in recent years, but faced an IRS lien and eviction lawsuits. It was forced to close its housing program less than three years after it launched.

Philadelphia and state officials awarded more than $6 million in taxpayer funds over the last five years to a politically connected but financially unstable anti-violence nonprofit, despite repeated warnings from city grant managers about improper spending and mismanagement, an Inquirer investigation has found.

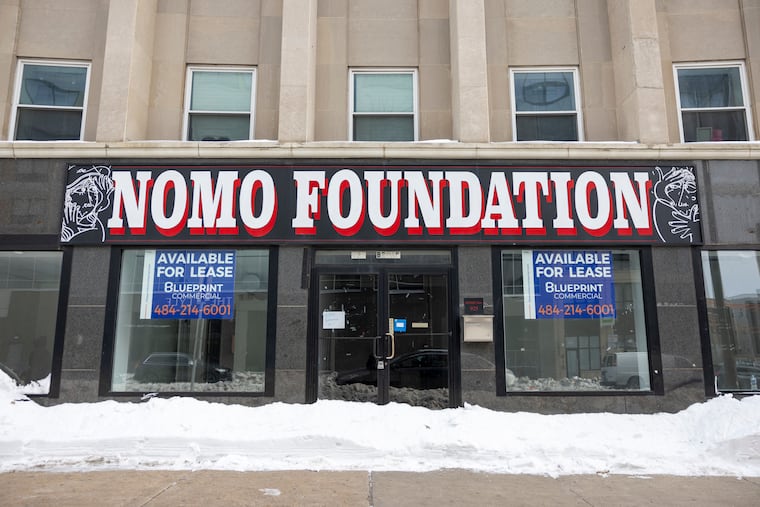

The group — New Options More Opportunities, or NOMO Foundation — received city and state anti-violence grants and locally administered federal dollars to expand its youth programs and launch a new affordable housing program. The money fueled NOMO’s rapid rise from a small, grassroots outfit into a sprawling nonprofit that took on expenses it ultimately couldn’t afford.

Mayor Cherelle L. Parker has publicly touted NOMO’s work in the community, and she further boosted its profile by naming its director to her transition team upon taking office. But behind the scenes, Parker administration staffers watched NOMO face mounting financial pressures over the last two years.

In that time, the organization has been hit with multiple eviction filings and an IRS tax lien, and had to lay off staff and suspend programming. Most significantly, NOMO had to terminate its housing initiative last year — displacing all 23 low-income households that had been its tenants.

The warning signs were evident years earlier. Records obtained under Pennsylvania’s Right to Know Law show that city grant managers expressed concerns as far back as 2021 about NOMO’s lack of financial controls, incomplete balance sheets, and chronic inability to provide basic documents. As recently as last year, the city was unaware who sat on the group’s board.

Yet records show city officials kept propping up the group with more funds, without successfully putting in place the kind of structural support that might have kept it from foundering. Last year, the city sought to award a $700,000 federal homelessness prevention contract to NOMO, but the nonprofit was unable to meet the conditions of the contract and the funds were never disbursed. Officials also proposed writing more funding to NOMO into last year’s city budget as a last-minute line item. That effort failed.

In a September interview, NOMO executive director Rickey Duncan blamed city officials for funding delays.

“I was breaking my back to make sure those young people were getting housed,” Duncan said. “We built a tab that was so big we couldn’t pay no more, because the city didn’t pay.”

Much of the money awarded to NOMO came via Philadelphia’s Community Expansion Grant (CEG) program, launched in 2021 to respond to record gun violence and support alternatives to policing. NOMO was one of only two initial grantees to receive the maximum $1 million award, which was meant to help the group scale up its operations and serve more at-risk youth.

A series of Inquirer investigations has shown that the CEG program’s politicized selection process awarded grants to fledgling nonprofits sometimes ill-equipped to manage the funds. The city controller in 2024 corroborated many of The Inquirer’s findings, and late last year the District Attorney’s Office charged nine police officers with conspiracy and theft of CEG funds.

NOMO’s financial records detail spending that quickly led to trouble after it received the first city grant, starting with the decision to devote most of the funds to launching a costly housing initiative while opening sprawling new youth centers to expand its after-school programs to new neighborhoods.

Duncan signed annual building leases totaling $750,000, and increased his own salary from $48,000 in 2021 to $144,000 the next year. (Duncan said that his pay — now $165,000, according to the most recent tax filing — is below average for an organization of NOMO’s size and was previously lower because he was volunteering half his time.)

The records contain no evidence that city grant managers questioned the lease expenses or conducted an evaluation of whether the upstart housing program was an appropriate addition to the organization’s core mission of offering after-school programming.

By the start of last year, a tax lien and lawsuits over unpaid rent threatened NOMO’s existence. Still, Duncan asked the city in January 2025 to reimburse the roughly $9,000 cost of two Sixers season tickets he purchased a year earlier. He explained in a memo that the tickets were “an innovative tool for workforce development.”

“Season tickets to the Sixers are not an acceptable programmatic expense,” the grant program manager responded in an email.

Records show that city officials discovered in April that a $35,000 IRS lien, filed four months earlier, had rendered NOMO ineligible for grant funding. Grant administrators sent an email to NOMO staffers with a warning written in all-caps: “CEASE ALL SPENDING.”

Duncan said the lien was the result of a missing signature on a tax form, and that it was eventually resolved at no cost. But in a June email to Public Safety Director Adam Geer and other city officials, he accused the city of pushing his organization to the brink of collapse.

“I am respectfully requesting a written response detailing how a tax [lien] escalated into a comprehensive investigation into the NOMO Foundation’s financial health,” Duncan wrote. “NOMO has been disrespected, attacked, and harassed, by members of this office on this and previous occasions.”

The funding was eventually restored last August.

Duncan and his nonprofit have maintained support from the city’s top elected leaders. Parker name-checked NOMO in her first-ever budget address, and City Council President Kenyatta Johnson appointed Duncan last year to an anti-violence task force.

In a statement responding to The Inquirer’s findings, Johnson praised NOMO and credited the organization with “working with children throughout Philadelphia, intervening in cycles of violence, and literally saving lives in our community.”

Johnson, who was listed as a reference on the group’s most recent grant application, added: “Regarding any allegations raised against Mr. Duncan and NOMO, I am confident that the City of Philadelphia’s Office of Public Safety will review these matters thoroughly, fairly, and professionally. It is crucial that any concerns are taken seriously and examined through the proper channels, with facts guiding the outcome.”

A spokesperson for Parker referred questions to the city’s Office of Public Safety, which manages CEG grants.

In a written response, a spokesperson for the department, Jennifer Crandall, praised NOMO’s efforts.

“Not only has NOMO delivered on grant-funded programs, it has become an important partner on city initiatives like interventions with at-risk youth,” Crandall wrote. She cited evaluations by an unnamed third party that credited NOMO for providing “holistic support to participants … beyond the immediate program activities” and “addressing the broader social determinants of violence.”

Crandall did not respond to a follow-up request for the evaluation.

Duncan gave The Inquirer a 2023 report prepared by four nonprofit partners that evaluated CEG recipients in their first year, with the intention of documenting program goals and activities. The report states that the evaluation was based on a single site visit, interviews with staff, and a youth focus group, and that it was then too soon to evaluate impact. It noted that NOMO had retained more than half its participants over the grant cycle and had created “an environment that is welcoming and comfortable, so that participants willingly show up.”

The assessment did not address the viability of the housing program, nor did it cite any metrics that might be used to gauge whether NOMO’s programs had reduced community violence.

Duncan also sent The Inquirer written statements from two landlords indicating that their court cases against him had been resolved, and that they support NOMO’s mission.

He says NOMO is now financially stable, despite three years of tax returns showing the nonprofit in the red. He said NOMO’s programs now serve about 140 children a year across its three locations — about the same as when it was operating in just one location in 2019 and before the city awarded the expansion grants.

Laura Otten, a nonprofit consultant and former director of La Salle University’s Nonprofit Center, said it was clear the city’s grant awards to NOMO had not fulfilled their stated goals.

“It obviously didn’t work if they ended up having to evict people,” she said. “Where is the evidence that this grant has improved the capacity of the organization?”

‘Significant weaknesses noted’

When Parker laid out her priorities in her first budget address before City Council in spring 2024, she mentioned Duncan and NOMO by name as she praised the grassroots anti-violence organizations “working each day to lessen the pain and the trauma caused by gun violence.” She also promised to reward the various groups with an additional $24 million in grant funding.

It was another highlight of Duncan’s well-documented redemption story. By his own account, he dropped out of South Philadelphia High School in 1994 to sell drugs and promote concerts, earning the nickname “Rickey Rolex” for his flashy style. He was arrested the next year for robbery and spent more than a decade in prison. After he was released in 2015, Duncan began volunteering with NOMO, then a fledgling nonprofit, and eventually took the reins.

“My vision started off, to be honest, just wanting to help kids and give back to a city that I took from,” Duncan said in a 2023 interview with The Inquirer.

NOMO began as a largely volunteer-run effort operating in borrowed space on less than $50,000 a year, tax returns show.

In 2019, the tiny nonprofit submitted a grant application to Philadelphia Works, the city’s workforce development board, which was tasked with distributing about $6 million in federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) grants. NOMO proposed after-school programs that would teach up to 125 kids everything from neuroscience to software development to road construction.

Philadelphia Works awarded NOMO $209,000, skipping the standard financial review in order to disburse funds that would have otherwise expired.

“It breathed life into us,” Duncan said.

By 2021, NOMO was receiving half a million dollars annually in TANF money — enough to lease a 7,000-square-foot office space on North Broad Street and support programs for more than 100 young people. And Duncan’s star was rising as a charismatic and credible voice who came up from the same streets that he and others were working to rid of violence. Elected officials and news media alike turned to him for quotes and photo ops amid a surge in shootings.

In December 2021, then-Mayor Jim Kenney announced a $155 million investment in gun violence prevention funding. The plan included a $22 million grant program, with more than half that focused on “supporting midsized organizations with a proven track record” to “expand their reach, deepen their impact, and achieve scale.”

Duncan’s scrappy, homespun nonprofit was exactly the type of group city officials had in mind when they created the CEG program, and his grant application cited support from State Reps. Danilo Burgos and Elizabeth Fiedler. Although 30 other nonprofits received funding, NOMO was one of only two organizations awarded the maximum grant of $1 million — a transformative sum that would roughly triple NOMO’s operating budget.

In his first application for the CEG funds, Duncan pledged to expand his “trauma informed” after-school program to South Philadelphia by offering paid work experience, academic support, and intensive case management. The $1.4 million proposed budget projected the organization would spend about $1 million annually on staff salaries and participation incentives for teens, while spending $94,000 a year to cover added lease costs.

NOMO devoted just one sentence of its 15-page grant application to describing a new affordable housing initiative “to combat youth homelessness.” The proposal did not include what metrics would be used to judge that program’s success.

Despite the brief mention, the housing initiative would become the organization’s largest single budget item, by far.

After securing the city grant money, NOMO took on a $552,000 annual lease for a newly built 27,000-square-foot West Philadelphia apartment complex near 40th Street and Lancaster Avenue. It also signed a $192,000-per-year lease for a 17,000-square-foot former culinary school on South Broad Street.

The deals left NOMO with youth centers in North, South, and West Philly, each with large event spaces that could host its programming. Duncan also planned to market the venues for private events — such as weddings and Eagles watch parties — to generate additional revenue.

If city officials had concerns about NOMO’s costly expansion strategy or the viability of his plan to lease out the youth centers for parties, they are not reflected in the available records.

However, staffers at the Urban Affairs Coalition — a nonprofit the city had contracted to manage the first round of the grant program — flagged NOMO’s general lack of financial controls in a December 2021 fiscal assessment of prospective grantees.

“Significant weaknesses noted,” an Urban Affairs staffer wrote of NOMO in an email to then-anti-violence director Erica Atwood and other city officials. “No audited financials. No balance sheets presented even in the [IRS Form] 990s. Separation of Authority: Basically non-existent.”

That month, the city instructed Urban Affairs to proceed with the scheduled grant advance of $200,000 and to work with NOMO to establish a remediation plan. Instead, grant administrators wrote that they were reassured after NOMO installed a new chief operating officer — who left the organization the following year.

By the end of the grant cycle, Duncan was able to deliver a public relations win for NOMO. He appeared on Good Day Philadelphia in December 2022 to launch the housing plan with a surprise giveaway of the first of 23 brand new apartments for young women, many of them single mothers.

Duncan said NOMO’s housing program would cover 70% of rent costs for 18 to 24 months while enrollees seek employment and eventually move out on their own.

“They’ll be getting their credit together so they can prepare to become a homeowner,” he told Fox 29. “We need money to finish doing this.”

Billion-dollar dream

The city renewed NOMO’s grant in January 2024, this time for $850,000. But a tax return the same year showed the organization was already $710,000 in the red.

Months later, the nonprofit faced its first eviction suit, targeting its North Broad headquarters, and had to cut a check for $275,000 in back rent — the equivalent of one-third of its city grant money for that year.

By the fall of 2024, records show NOMO had spent only about 5% of the $150,000 initially budgeted for youth incentives, outside activities, equipment or program supplies. The city withheld most of NOMO’s fourth-quarter grant funding, reducing the nonprofit’s award by $170,000 to a total of $680,000 for that year.

Still, the city reupped the group for a third grant in 2025, this time for $600,000.

By January 2025, financial records show NOMO had virtually stopped spending on youth programming. It laid off most of its staff as landlords for all three youth centers took legal action against the nonprofit over hundreds of thousands of dollars of back rent.

Around then, NOMO received an infusion of support in the form of a $950,000 grant from the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency. But the TANF funds had run out, and the organization’s problems continued. City officials had NOMO submit a formal “performance enhancement plan” last July.

Duncan said in September that NOMO had cut costs, hired a new accounting firm, and is working toward “full financial stability.” It resolved two eviction cases by reducing its real estate footprint — downsizing its North Philly headquarters into basement offices and terminating its affordable housing program. Duncan said the former tenants moved in with family members or were transferred to the nonprofit Valley Youth House, which provides transitional housing.

After The Inquirer asked Duncan about the most recent lawsuit over back rent, this one for $312,000, his landlord filed notice in court that the matter was resolved. Duncan said keeping three youth centers and marketing the NOMO spaces for special events are key parts of his business plan as the organization continues to settle its debts.

The spate of lawsuits has not dampened the city’s enthusiasm for Duncan’s nonprofit. Crandall, the spokesperson for Philly’s Office of Public Safety, said NOMO remains eligible to receive funds when a new round of grants are awarded this year.

And with the housing initiative scrapped, NOMO is left pursuing its original mission — anti-violence programming for city youth. The organization’s renegotiated leases for its three youth centers now total $360,000 a year, roughly half what NOMO had been paying.

In a 2023 interview, Duncan acknowledged that he underestimated the financial demands of running an organization on a citywide scale.

“As a kid you think, … ‘If I can get a million dollars, I’ll be rich.’ And then you’re broke again,” he said then. “I had a billion dollar dream. I didn’t realize it was a billion dollar dream.”