As hate crimes surge, Philly Holocaust Memorial is reinvented with an antiracist mission

“Within the younger generation, what we see is a lost connection to this history. And instead of foundational education being in place, there is a propaganda machine on social media.”

Hate crimes in the United States are at a 10-year high. Anti-Semitic and racist incidents have been on the rise in the pandemic, surveys have found. And the nation is still coping with the aftermath of an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, where blatantly anti-Semitic imagery abounded, right down to a man in a “Camp Auschwitz” hoodie.

Against that daunting backdrop, the Philadelphia Holocaust Remembrance Foundation has launched a new endeavor to counter bigotry of all kinds with a curriculum the organization is calling “History is Now.” It highlights through-lines connecting Jewish persecution in Nazi Germany with the oppression facing marginalized groups to this day — including how misinformation and propaganda have fueled hate and sparked violence.

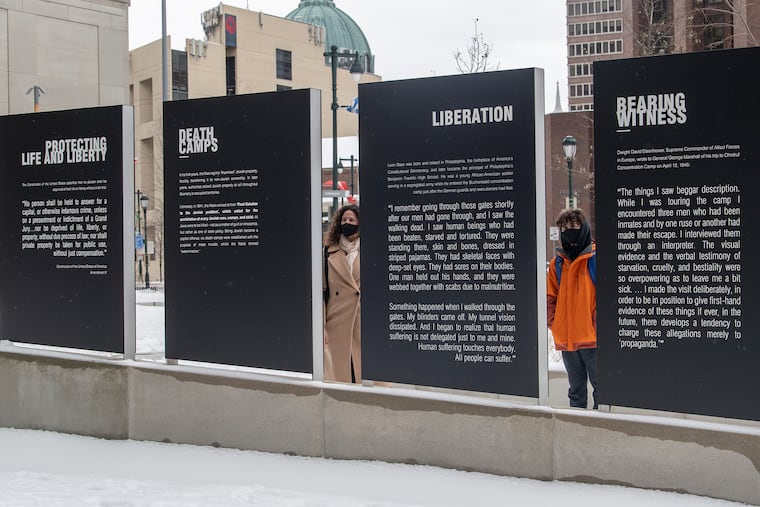

The campaign includes an app-based walking tour of the memorial site at 16th Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. It was the first Holocaust monument in the country when it opened in 1964 and received a $7 million makeover a few years ago, transforming the space into an open-air museum and classroom. It also has brought a new curriculum to Philadelphia public schools, teaching Holocaust education through a contemporary and intersectional lens.

“Particularly within the younger generation, what we see is a lost connection to this history,” said Eszter Kutas, executive director of PHRF, citing a survey of millennial and Gen-Z Americans that found about one in five were not aware of the Holocaust, and half could not name a concentration camp. “And instead of foundational education being in place, there is a propaganda machine on social media. It’s hateful, it’s discriminatory. ... Our foundation therefore decided to make a concentrated effort to bolster our education and apply it to present-day problems.”

Recently, Kutas led a training for about 35 Philadelphia social studies and history teachers, walking them through detailed lesson plans the organization has developed.

One is devoted to Leon Bass, a former principal at Benjamin Franklin High School who served in the segregated Army during World War II and helped liberate the Buchenwald concentration camp. The shocking conditions he witnessed, along with his own experiences of racism, led Bass to become a vocal human-rights activist.

Another is a history lesson about the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics, the international debate about whether to join, and the experiences of both Jewish and Black American athletes. “It explores how both participation and boycott can be a form of protest,” Kutas said.

Julie Webb, a history and Spanish teacher at Swenson Arts and Technology High School in Northeast Philadelphia, said the training was her first introduction to the memorial. “I was ashamed to say I never knew about it, and proud that so much thought and development went into its building,” she said.

The renovations, completed in 2018, include informational signage, six pillars representing the six million Jews who were killed, and, embedded into the plaza, sections of train tracks that once led to the Treblinka concentration camp. The app, created in collaboration with the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation, allows visitors to hear the voices of survivors who rode that train.

New interactive tours, added as part of the “History is Now” campaign, include one on propaganda and another on contemporary anti-Semitism.

One element of that tour is a video clip of an interview with Judah Samet, a Holocaust survivor and 40-year member of the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, where 11 people were killed in a mass shooting in 2018. Samet was running late that morning, and was not inside the sanctuary. He said he thought to himself: “For me, it’s never over. For my family, it’s never over. It was a reference to the Holocaust and everything else.”

Webb expects that the lessons will resonate with her students. “I think explaining the intersectionality of racism and anti-Semitism helps students transfer the knowledge or feelings they have and connect that to other people’s experiences.”