For some Philly tenants, eviction diversion comes too late. Or not at all.

Despite the mediation program’s success, it’s up to landlords to initiate it.

After Charles Cook fell on hard times and lost his New Jersey home last year, a modest room in a North Philadelphia rowhouse was supposed to be a fresh start.

But the 71-year-old noticed some electric sockets weren’t working after moving in. Others appeared outdated, like they could shock him.

After months of back-and-forth with his landlord, the dispute reached a breaking point in July, when Cook’s landlord illegally locked him out of the property.

Cook wandered the streets and slept on a park bench.

City code requires landlords seeking to evict a tenant to file a complaint in municipal court, though the process doesn’t happen on demand. A hearing, and ultimately a judge’s ruling, are required before an eviction. But Cook’s lawyers say his landlord never filed a complaint to begin with.

Cook was the victim of one of an estimated 20,000 illegal evictions that occur in Philadelphia each year, his lawyers say.

The city has a program to avoid such evictions, the Eviction Diversion Program.

Housing experts call Philadelphia’s Eviction Diversion Program one of the “best-designed” in the country, crediting the program for keeping evictions below pre-pandemic yearly averages since it launched in 2020. So far, the program has diverted around 3,000 lockouts, and last year, City Council voted to extend it though the beginning of 2024.

But not all tenants, like Cook, get the chance to participate.

Landlords must begin the program — a 30-day period where tenants can negotiate their conflicts in the presence of a trained mediator, hopefully avoiding an eviction filing altogether, let alone a judgment.

“Diversion is a voluntary program, and it can’t take care of tenants whose landlords want them out instantly,” said Francine Wilensky, an attorney with the SeniorLAW Center, which offers legal resources to vulnerable renters in disputes with their landlord. “It has to involve two people who are working together.”

Wilensky said it’s common for landlords to bypass the diversion process because they have not maintained their certificate of rental suitability, which signals to the city’s L&I department that the property is free of violations and is safe and habitable. Others fail to possess a license at all.

Though some landlords are unaware that the city requires them to offer diversion, she said, most know their practices are unlawful.

“I find it hard to believe that a landlord who is illegally locking out a tenant is doing so because they don’t know how to navigate the court process,” said Rachel Garland, an attorney with Community Legal Services’ housing unit, which also offers legal help to at-risk renters and those who otherwise couldn’t afford counsel.

Sometimes, landlord-tenant cases do make it to diversion — but not until disputes have spun out of control.

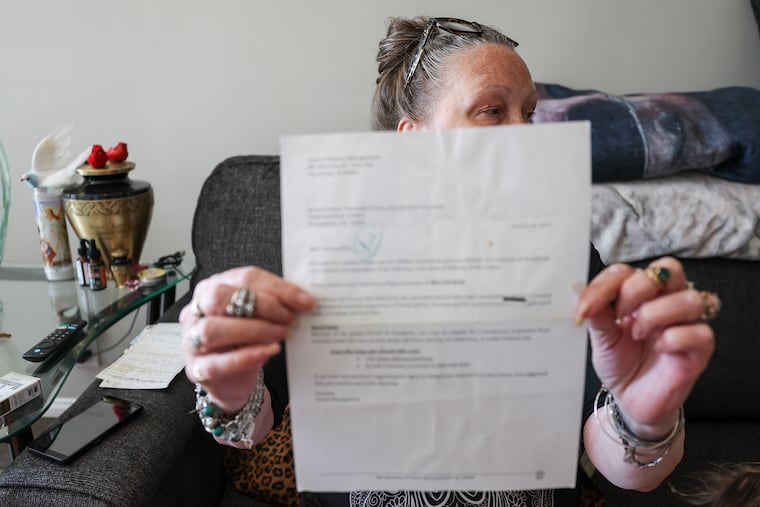

For Donna Kuzowsky, a 63-year-old Mayfair resident, an earlier opportunity for mediation could have saved her months of anguish.

It was a chilly January morning in 2022 when Kuzowsky opened the door of her rented rowhouse to find a notice from a property management company based in South Carolina that she’d never heard of.

Kuzowsky had 10 days to pay over $3,000 in back rent, or face legal proceedings to remove her, the company wrote.

Without Kuzowsky’s knowledge, her old landlord had sold the rental she’d lived in since 1999 to an ownership group six months earlier. She said she had continued to wire her rent money to her old landlord, who she claims never notified her of the sale.

Kuzowsky tried explaining her situation to the new owner’s property manager, Conrex Property Management. But the dispute only intensified, according to her lawyers.

A spokesperson for Conrex said that the company did nothing illegal, and had tried calling and mailing letters to Kuzowsky after the ownership change. She said she never received them.

Eleven months later, in November 2022, Conrex filed to evict Kuzowsky in municipal court, where she was offered the mediation period. But by then, Conrex had already attempted to evict Kuzowsky another way: filing a civil ejectment complaint, bringing her longstanding lease into question, and labeling Kuzowsky a squatter, her lawyers said.

Garland, with Community Legal Services, said the city’s diversion program is a valuable resource for tenants — but only if their landlords are prepared to negotiate in good faith. Even then, completing the mediation period doesn’t guarantee that a landlord won’t continue with the eviction filing anyway.

When mediation isn’t offered at all, tenants like Cook seek help elsewhere.

The Philadelphia Police Department is another resource available to tenants. According to a department directive, officers must contact the landlord when a tenant reports an unlawful eviction.

During these calls, officers are supposed to ask landlords for proof of a judgment of possession from the court. But too often, Wilensky said, police fail to reach out, opting to only file a report.

“If police made these calls more frequently, landlords behaving illegally would feel more pressure to follow the proper eviction protocol,” Wilensky said.

When Cook was locked out of his apartment for days this summer, it wasn’t until his lawyers contacted the Attorney General’s office, which in turn called Cook’s landlord, that he was let back into his unit. The office regularly offers assistance to tenants facing illegal evictions, and can be an appealing alternative to the police for some wary renters, Wilensky said.

For Kuzowsky, facing eviction in Mayfair, the 30-day diversion period didn’t lead to a resolution, and the new ownership group continued with the eviction process. With the help of her lawyers, however, Kuzowsky agreed to move to a nearby property in June.

She avoided an eviction judgment, but at a cost.

Kuzowsky’s granddaughter teared up as they packed. The house was full of two decades of memories, she said, especially of Kuzowsky’s late husband, Steven.

Asked whether she would have purchased the home herself, had she known it was on the market, she said: “I would have done it in a heartbeat.”