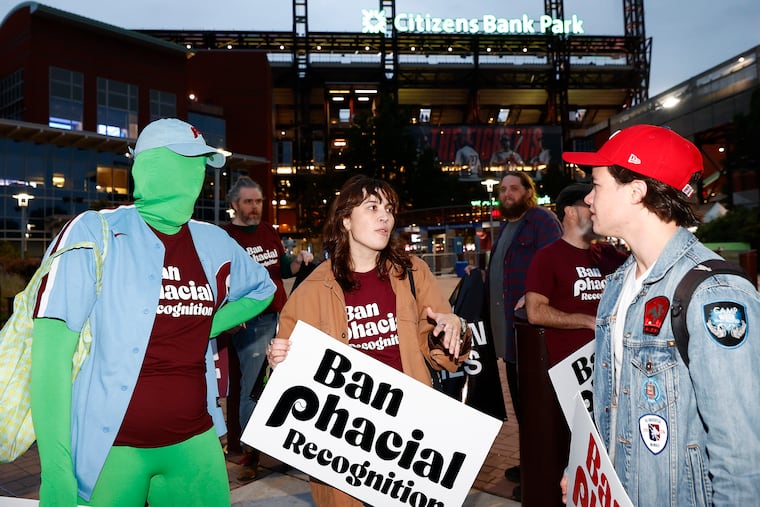

Privacy advocates protest the Phillies’ use of facial scanning for Citizens Bank Park entry

Privacy advocates protested the Phillies’ use of facial recognition technology for ballpark entry.

Engulfed in the stretchy fabric of a neon “green man” suit, Mia Kashuba’s face was fully concealed outside Citizens Bank Park on Thursday.

The 25-year-old Philadelphian wasn’t there for the game. She was protesting Major League Baseball’s use of facial-scanning technology.

“There’s this normalization of facial recognition in our society in places where we don’t necessarily think about it,” Kashuba said. “The more we normalize it here in the MLB, the more it will become an issue in other parts of our lives.”

This summer, the league announced that the Phillies would be the first of its teams to roll out a facial-scanning service, Go-Ahead Entry. Ticket holders snap a photo of their face and upload it to MLB’s Ballpark app ahead of the game. At select gates, fans pass a Go-Ahead camera, which verifies their identity and allows for entry without having to produce a ticket.

MLB officials say the technology lets fans conveniently bypass lengthy lines and get to their seats.

But digital privacy groups like Fight for the Future, which organized Thursday’s protest, are adamant that face scanners don’t belong anywhere near the hallowed grounds of America’s pastime — or anywhere at all.

“This technology poses unprecedented threats to people’s privacy and safety, said Leila Nashashibi, a member of Fight for the Future. ”This tech is trying to solve a problem that doesn’t really exist. People can easily manage tickets on their phones, or paper tickets. It’s completely unnecessary.”

More broadly, Fight for the Future says the widespread use of facial scanning leaves its users’ most valuable data — their likeness — vulnerable to hackers, while creating the potential for weaponization by law enforcement agencies.

Hoisting signs that read “Ban Phacial Recognition,” members handed pamphlets to curious fans straggling in for the Phillies’ losing outing against the Pirates.

Despite the opposition, MLB is the just the latest player to get in on the technology.

In recent years, teams across the NFL, NHL, NBA, and MLS have rolled out the software at select stadiums for both ticketing and security. Recurrent usage among fans is so popular, according to one facial recognition software executive, that “once you’re in, you don’t go back.”

But while the $42 billion per year biometric systems industry welcomes expansion, protesters like Kashuba are sounding alarm bells.

Ken Mickles, Fight for the Future’s chief technology officer, said he’s been concerned about the creeping influence of biometric technology for two decades.

“I do not trust the security of these things,” Mickles said. “There’s a story about hacks more or less every week. It seems like you would have to be pretty foolish to trust any corporation.”

MLB disagrees.

The league has maintained that the Go-Ahead Entry exists for “facial authentication,” not recognition, and that it had gone to great lengths to protect users’ data.

“In accordance with MLB’s Privacy Policy, Go-Ahead Entry cameras will scan your face to create a unique numerical token associated with you,” the league wrote in an FAQ. “The facial scans will be deleted immediately thereafter. Only the unique numerical token will be retained and associated with your MLB account.”

“Our basic response is, we don’t buy it,” Nashashibi said, citing recent revelations that digital verification company ID.me had misrepresented how it handles its users’ face scans.

Phillies fans, meanwhile, have begun to warm to the service.

Ahead of the team’s three-game series against the Los Angeles Angels last month, at least 7,000 fans were reported to have opted-in to Go-Ahead’s services (participation is optional, MLB has emphasized in press inquiries).

“The facial authentication process of Go-Ahead Entry is safe, secure, and solely used for the expedited, frictionless ingress into the stadium for fans who opt-in,” said Chris Marinak, MLB’s chief operations and strategy officer, in an email Thursday. “No images are stored in the system and it is not being used for security monitoring.”

Fight for the Future, however, says the technology — no matter its intended purpose — contributes to larger, more concerning trends.

Nashashibi pointed to the controversial banning of critics and their associates last year from Madison Square Garden by the event venue’s billionaire chief executive, James Dolan.

How the bans were enforced? By using the same facial recognition technology the venue uses for security checks at entry points.

Denied entry were lawyers who worked at firms that had sued Dolan’s company, including those who weren’t directly involved in the litigation.

Meanwhile, in Brazil this month, police made nearly 30 arrests after a popular Sao Paulo soccer team helped them identify criminal suspects using its stadiums’ facial recognition software for ticketed entry.

That coincides with U.S. state, federal, and local law enforcement ramping up efforts to access private consumer data collected by corporations using subpoenas and court orders.

The Brookings Institution, for example, found that over six months in 2020, agencies made some 112,000 of these demands. The results — especially for Black and brown communities — can do more harm than good.

“Obviously, the Phillies have been a big part of my life,” Kashuba said through the green fabric over her face. “But the implementation of facial recognition technology in the stadium feels like it could be a problem in the future.”