Pittsburgh-area man’s quest to find a family shown in photos taken from a dead Japanese soldier

Many families of Japanese soldiers killed in the Pacific received little more than a wooden box containing the man’s name and a pebble signifying his remains, it was almost like they never existed.

Famed World War II correspondent Ernie Pyle once wrote that “all Marines are souvenir hunters.”

So it may have been with Sgt. Harry Dininger of the 22nd Marine Regiment.

Bob Dininger and his brother Harry are both from Freeport, Armstrong County.

Among his correspondence from the Pacific to his parents in Freeport in 1944, he included five photos he had likely acquired from a dead Japanese soldier in the Marshall Islands.

He sent them home to show his family what the Japanese were like. A year later he was dead, too, cut down by a bullet on Okinawa at age 25.

The five photos are: portraits of a Japanese family of five, with three children and their parents; a man and a boy; a shirtless young man wielding a bokken, or wooden training sword; a woman in a kimono; and a man, also in a kimono.

Seventy-seven years later and half a world away, Harry’s great-nephew is trying to find out who those people were and return the photos to their relatives.

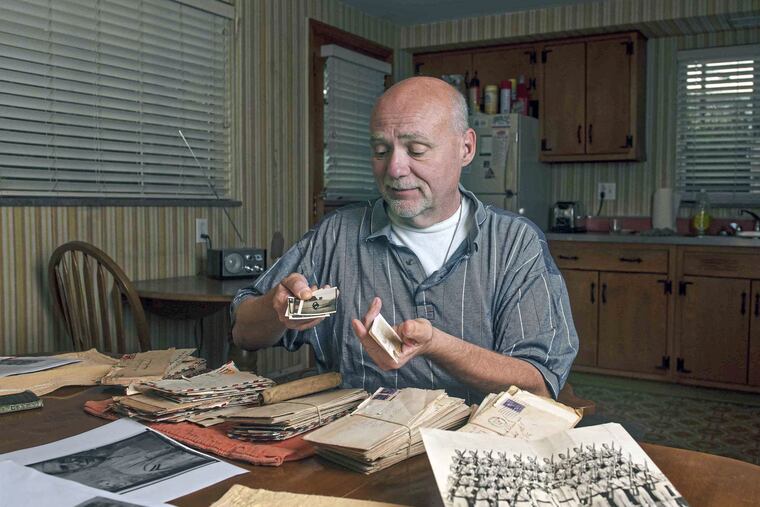

David Wassel, 59, of White Oak, discovered them in the home of Harry’s brother Bob, also a World War II combat veteran, when he was cleaning out the house after Bob died.

With the help of a Japanese journalist and producer, he’s contacted Japanese authorities and given interviews to Japanese media in an effort to provide a sense of peace for a distant family.

The reason is simple: empathy for a former enemy.

Harry Dininger’s remains came home in 1949.

But many families of Japanese soldiers killed in the Pacific received little more than a wooden box with a piece of paper containing the man’s name and a pebble signifying his remains, or perhaps a piece of coral or some sand to represent where he died.

With no bones, no artifacts, no dog tags, it was almost as if these men never existed.

“Harry’s family at least had a body. These people got nothing except maybe a pebble,” said Wassel, an attorney.

Mariko Fukuyama, an independent producer for Japanese media based in New York, has helped Wassel get the story out across Japan during the last year.

In May she visited White Oak and Freeport to help Huffington Post Japan and the Mainichi, the national newspaper, interview Wassel and shoot video, and she was back last month to do the same for a TV Asahi segment that was set to air last Friday night to coincide with the anniversary of the Japanese surrender on Aug. 15, 1945.

For her, the photos feel almost personal.

“They really speak to my heart — how close they look like my own family,” she said. “Many Japanese families would probably feel the way I felt when I saw them.”

Long-ago photos often resonate with families on both sides of history’s most catastrophic war.

Pictures tend to humanize an enemy. Soldiers saw that the people they were fighting were not faceless warriors but young men like them, with parents, siblings, and sweethearts.

The Marines were not the only souvenir collectors; a picture of Harry was also recovered from a dead Japanese soldier, likely taken from Harry’s pack after he’d been wounded on Guam.

‘I have to find the family’

Like millions of young Americans, Harry and Bob Dininger did their duty during America’s darkest hour.

Harry, a three-sport letterman at Freeport High School and president of the Class of 1938, had joined the Marines before the war began and shipped off for the Pacific, seeing action in several island battles. Bob, older by eight years, became a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne and landed at Normandy on D-Day, later fighting in the Battle of the Bulge.

After Bob died in 1999 and his wife, Mary, died in 2002, Wassel found a box of 170 letters in the basement. Bob and Harry had written to each other and to their parents throughout the war. Wassel pored over the correspondence and felt transported to another time.

“I went through those things and read the letters and it was other-worldly,” he recalled. “These people didn’t know how this [war] was going to turn out.”

Typical of the time and that generation, Bob and Harry tended to understate the hardships and danger. Wartime censorship also curtailed any detailed description of action or location. Harry often just said everything was “swell.” The sentiment was not to worry the home folks.

Wassel, whose Marine father fought in Vietnam, had heard stories of World War II from Bob over the years. He wanted his own great-nephew, 9-year-old Chase Wassel, and Chase’s 2-year-old brother, Ezra, to someday understand their connection to the war years.

“I’d like this to mean something to them, as well as other young people, in both the United States and Japan, and for them all to take from this a genuine appreciation of history in general and the roles that their own families played in particular,” Wassel said in an email. “That’s another reason that finding out who was this young Japanese soldier is so important. It gives young people in both countries the stories of their own countrymen and that of the other country.”

Harry never said where he got the photos. Based on the date of the letter, he likely obtained them after fighting on Engebi and Parry islands in February 1944. Some 2,000 Japanese soldiers died on those islands.

The Marines in the Pacific, as Ernie Pyle wrote, routinely took items from corpses and sent them home. Especially prized were samurai swords and “comfort flags” carried by Japanese soldiers as good-luck tokens in combat. The Marines also searched bodies for intelligence to help the campaign.

However Harry came by the photos, he wrote home: “I sort of thought you would like to see what the people we are fighting look like.”

Freeport was a small town then as it is today, and “these are probably the first Asian people Harry had ever seen,” Wassel said. “I think he was curious.”

Wassel said he felt sympathy for Harry and for the dead Japanese soldier, both young men killed in their prime in a war that left millions dead.

He had long felt the photos should be returned to their owners, but he wasn’t sure where to turn.

Fukuyama became his conduit. In 2018 she spent a few weeks in Uniontown covering the midterm elections and met Wassel, who was doing legal work for the Democratic Party. She later returned to Pittsburgh to cover the Tree of Life synagogue shootings.

Wassel stayed in touch with her by email and in 2020 mentioned the photos. She was busy at the time and didn’t respond, she said. In March he sent her the photos.

“That’s when I realized these are family photos,” she said. “I said, ‘I have to find the family.’”

The family portrait in particular made an impression, especially the clothing; her own grandmothers had worn similar kimonos.

She got in touch with the Marshall Islands War-Bereaved Families Association, made contacts with her media colleagues, and contributed to several stories. The exposure generated a buzz but no leads. At one point the Marshall Islands group reached out to the daughter of an actor, thinking he might be the young man with the sword. But the woman said her father was not the man.

A mystery man

After the Marshall Islands fell, the U.S. took Guam in July and August 1944. Harry fought there and was shot in the arm. He spent several months in a hospital on New Caledonia.

“My arm is coming along swell and is healing up remarkable, be good as new in a short while,” he wrote to his parents. “I sure would like to hear from you soon, so I could find out how things are going with Bob over on the other side. Right now things as a whole are going mighty good.”

Earlier that August, as the Allies pushed across France after D-Day, Bob sent a hopeful letter to his brother — he addressed him as “kid” — saying the European war might be over soon. After that, he said, “the full force of our men can be turned in your direction. Don’t get me wrong, I am not trying to insinuate that you need help, but it sure would speed things up. After all, that’s of utmost importance, the day when you and I can get back to the ‘village.’”

It wasn’t to be.

The Germans were far from finished and counterattacked at the Battle of the Bulge that winter.

In the Pacific, Harry recovered from his wound and returned to action for the invasion of Okinawa, the last major campaign of the war, in the spring and summer of 1945.

The war in Europe finally ended that May with the German surrender, but the Japanese gave no sign of giving up as the Allies pushed toward the home islands.

Harry remained optimistic in his letters and even took a dig at his Army brethren. He said the Marines had taken their part of the island but the Army was “fouled up” and might need the Marines to help.

“The dogfaces might be good over in Europe, but they aren’t any good out here, but if I go down there, there isn’t nothing to worry about,” he wrote.

He closed that letter with a P.S.: “Please don’t worry Mom, as the way I see it I don’t think of anything happening to me.”

Harry met his end at a place called Charlie Hill near Naha City, where the Marines struggled to take and retake a high ridge from determined Japanese defenders. On May 10, 1945, a machine-gun slug hit him in the chest. He died instantly.

Robert O’Brien, a sergeant major from Freeport who had grown up with Harry and served in the Pacific, sent a letter to Harry’s parents.

“I won’t attempt to say that he died for the American way of life, freedom, etc.. ... What I will say is that he died bravely, and quickly, which is the best way for a soldier to die, if he has to die at all.”

The Battle of Okinawa cost 12,520 American lives — including Ernie Pyle — and left more than 36,000 wounded. About 110,000 Japanese soldiers died, along with as many as 150,000 civilians. The tenacity with which the Japanese fought proved to be a deciding factor in the U.S. decision to drop the atom bomb in August.

Harry was buried on Okinawa. His hometown newspaper announced his death on the front page, including a picture of him. His body was shipped home in 1949 and buried in Lower Burrell. His tombstone is there today, next to his mother’s. Wassel and Fukuyama have visited the grave site in recent months and left flowers.

But the Japanese soldier whose pictures Harry took?

He remains a mystery man.

Part of the problem in finding him has been COVID-19. The National Institute for Defense Studies archives in Japan and other libraries list the names of those Japanese soldiers who died in the Marshall Islands, but they have been closed. The names aren’t online because of privacy concerns, Fukuyama said. What’s more, she hasn’t been able to go home since December 2019.

The Huffington Post story that ran in the spring drew some 350 comments online. Wassel and Fukuyama are hoping the TV program that ran on Friday, with its national audience, will prompt someone in Japan to come forward. Fukuyama said the Marshall Islands group also recently began circulating copies of the photos by mail among its dwindling members.

Someone out there, Wassel said, must know who those people were.

“We’ve narrowed it down. We know where Harry was, we have a timeline, and we know some of the Japanese units,” he said. “But nobody’s come forward yet to say, ‘This is my family.’”