White supremacists and other extremist groups are using protests and a pandemic to amplify their message

Extremists have latched onto the movements and used a playbook they’ve long relied on: establish legitimacy during a crisis, both in-person and online, to win new members.

As ideological unrest has gripped the country while it navigates dual crises in the coronavirus pandemic and the killing of George Floyd, far-right extremists have found opportunity in the social and political upheaval.

Groups have used a playbook that experts say extremists have long relied on: Latch on to in-person and online movements, whether they agree with the message or not, to establish a foothold in new communities, recruit members, and, in some cases, simply sow mayhem.

Last month, “reopen” protesters raged against state-mandated shutdowns amid the pandemic. The rallies at capitol buildings across the country were generally organized by mainstream conservatives, and most supporters were concerned about the deepening economic crisis.

But “reopen” communities also attracted antigovernment types, conspiracy theorists, vaccine skeptics, and militiamen — all people whom experts say white supremacist groups, including one in South Jersey, targeted for recruitment.

Then in May, after a Minneapolis police officer killed Floyd and sparked an uprising against police brutality, a variety of fringe actors were present at protests that in some cases turned to property damage. Experts said the goal may have been simply to create chaos. While public officials in a handful of American cities including Philadelphia said “outside agitators” caused trouble, few specified organizations or provided evidence.

For some extremists, protests have become a platform.

“When you have people who have divisive or even violent goals showing up at these kinds of highly charged rallies," said Brian Levin, director of the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University-San Bernardino, "it gives them the opportunity to spread their message in a forum and with an audience they wouldn’t normally have.”

Online to IRL

Studies suggest white supremacist groups gained a new foothold online as the pandemic kept Americans at home. In early April, engagement with white supremacist content on Google increased by 21% in states with stay-at-home orders in place for 10 or more days, according to Moonshot CVE, a London-based firm working against violent extremism. In New Jersey, the increase was 41%, a figure the researchers calculated by studying Google search volume.

Amid the lock downs, online messaging associated with an ascendant far-right group called the Boogaloo boys — who believe a second civil war is imminent — became “increasingly extreme," according to the Network Contagion Research Institute, a nonprofit that tracks hate online. The group determined the spike by analyzing thousands of comments on far-right message boards.

“We’re in quarantine. Everybody’s home, everybody’s online. So this is a kind of watershed moment for the far right,” said Colin P. Clarke, a senior research fellow at the Soufan Center, a nonprofit threat and security research organization. “I think we’re going to look back on the first half of 2020, and this is going to be the moment when a lot of these far-right extremist groups get a huge morale boost.”

Extremist groups used the reopen rallies and their online communities to recruit followers who view government-mandated quarantine as overreach, an important part of far-right ideology, said Joshua Fisher-Birch, a researcher at the nonprofit Counter Extremism Project. He said a person prime for recruitment might believe conspiracy theories related to the virus’ origin or the government’s motivations, and extremists “apply their own conspiracy theories in an effort to try to draw people to their cause.”

» READ MORE: New Jersey declared white supremacists a major threat. Here’s why that’s groundbreaking.

Clarke said some groups — particularly those who see themselves as fighting government tyranny — are buoyed by President Donald Trump, who “dog-whistled” to them by tweeting to “liberate” states with shutdown orders. The president and members of his administration repeatedly referred to the coronavirus as “the Chinese virus,” which experts say fuels racist propaganda.

Trump’s rhetoric isn’t new. Plagues have been blamed on Jews, immigrants, and people of color for generations, said Shira Goodman, director of Anti-Defamation League Philadelphia, which serves eastern Pennsylvania and South Jersey.

“We’ve seen that kind of ugly language, particularly online, and we’re seeing some of it at these rallies,” she said. “We know these people meet online and social media has created spaces where they can share beliefs. Now they can finally connect in real life.”

‘An audience they wouldn’t normally have’

White supremacist organizations and far-right groups, while not monolithic, aligned themselves with reopen protesters early on. For example, in May, someone flew a flag with the symbol for the Three-Percenters, considered part of a growing antigovernment extremist movement, outside Atilis Gym in Bellmawr, Camden County, which defied shutdown orders.

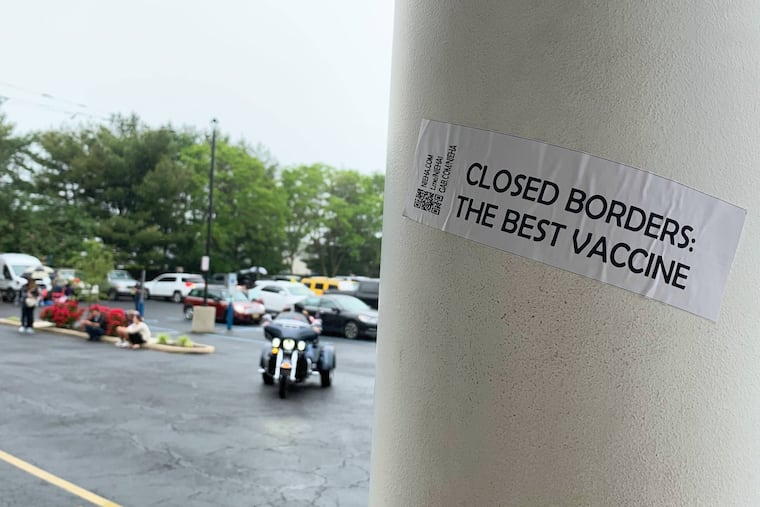

The New Jersey Office of Homeland Security and Preparedness also said a small white supremacist group based in South Jersey distributed propaganda at several reopen protests.

The organization, the New Jersey European Heritage Association, appeared last month outside a South Jersey Baptist church that reopened against state closure orders. A man approached 63-year-old Donna Lee of Voorhees, who wore a “Make America Great Again” hat, and handed her a flier that read “It’s time to put American first” and listed such demands as “build the wall” and “no homosexual marriage.”

The group’s social-media channels are a grab bag of racism and anti-Semitism. They blame the pandemic on Jews and immigrants, and posted photos of Gov. Phil Murphy with the words sic semper tyrannis, a Latin phrase meaning “thus always to tyrants" that’s believed to have been said by John Wilkes Booth after he shot Abraham Lincoln. In an email to The Inquirer that included anti-Semitic tropes, NJEHA said it “rejects” being called white supremacist.

In some cases, reopen rally organizers said they didn’t know far-right extremists attended until afterward.

A sticker with the NJEHA logo made it into the mainstream media this month after someone handed a branded megaphone to Ian Smith, the co-owner of Atilis. Smith, who became an example of defiant reopening, was photographed using the megaphone, and NJEHA’s logo and website were amplified.

A lawyer who represents Smith said his client “can’t control who shows up in a public parking lot” and didn’t ask the NJEHA to come. James Mermigis of Mermigis Law Group, which has represented other businesses defying state closure orders, said: “We do not support any message that they’re trying to promote.”

Outside agitators

There were a handful of examples of fringe actors showing up at protests after Floyd’s death, allegedly attempting to instigate violence.

In Philadelphia, Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw, the first black woman to head the department, said some of the people responsible for property damage came with the intention to inflict harm “and, quite frankly, those folks didn’t look like me.” She didn’t specify an ideology.

The president has blamed antifa, which stands for anti-fascist and which right-wing media personalities and the president have made a catch-all term for the far left. The big difference between antifa and right-wing fringe groups is the endgame, Clarke said.

“Antifa is a reactionary movement formed in protest to fascists. If fascism goes away, in theory so would antifa,” he said. “White supremacists are formed because they want a white ethno-state.”

Experts generally don’t consider antifa an extremist group, but some who consider themselves antifa-affiliated are anarchist extremists who have used violence as a tactic. Some witnesses described anarchist tactics leading to bedlam on the streets of Philadelphia in the wake of Floyd-related protests.

» READ MORE: As Trump blames Antifa, protest records show scant evidence

They weren’t the only “outside agitators” officials said planned to show up at protests against police brutality.

In Las Vegas, authorities arrested three men who were self-proclaimed “Boogaloo” boys for allegedly conspiring to incite violence at a protest against police brutality. The idea of the Boogaloo, sometimes called “the big luau,” began as a racist meme and has morphed into a growing online subculture that attracts militia enthusiasts. Members of the group attended reopen protests while carrying guns and wearing Hawaiian shirts, the group’s de facto uniform.

There’s overlap between those who subscribe to the “Boogaloo” ideology and white supremacist networks, though some Boogaloo believers claim to support protests against police brutality.

“The Boogaloo boys can’t even agree whether they’re racist or not," Levin said. “The same kind of fragmentation that has caused us to have 29 candidates running for president has also affected the extreme.”

But the ideology is gaining traction online, and experts worry it will inspire more violence or a muddling of the activism they’re trying to infiltrate.

This week, a California man was charged with murder after officials said he ambushed two deputies in Santa Cruz County, killing one officer and critically injuring another.

Before he was apprehended, prosecutors allege, he scrawled on the hood of a police car in blood “boog."