Aging South Jersey agricultural warehouses still display old-fashioned sayings

The walls used to be more of a landmark, but then many of the letters started disappearing over the past 30 years.

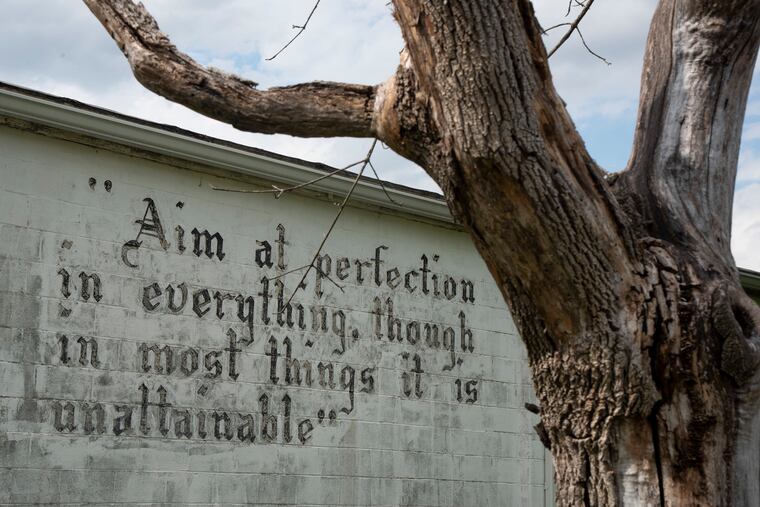

In Woodstown, Salem County, the old walls of a cluster of seven working warehouses display even older sayings — bromides from another time bracketed in quotes and rendered in calligraphic elegance.

The now-fading messages painted in black letters on white walls convey homey sentiments, existential meditations, and corny aphorisms that passed for social media in the mid-20th century:

“Keep your face to the sunshine and you will not see shadows.”

“The greatest, the most important of the arts is living.”

“In quarreling the truth is always lost.”

As pandemic protocols loosen and the coming Memorial Day weekend signals the start of summer travel season, the walls will serve as a little-known roadside attraction for beach-bound motorists using back roads — in this case N.J. Route 45 south — to roll through bucolic Woodstown toward the Atlantic Ocean, about 50 miles east.

“The walls used to be more of a landmark, but then many of the letters started disappearing over the past 30 years,” said Michael Vassaras, 59, a forklift driver for CPS Distribution, a freezer warehouse that operates four of the buildings. “Still, the walls are the only thing outsiders know about Woodstown other than Cowtown Rodeo,” which, as Vassaras may hate to hear, is technically in adjacent Pilesgrove.

Vassaras said his favorite wall-displayed phrase includes the line “The steam that blows the whistle never turns the wheel.”

” There’s deep truth in that, said Vassaras, a working man all his life, “because the noisemakers of the world don’t really work.”

According to Vassaras’ boss, John Ober, president and owner of CPS, the idea of mixing business with reading pleasure originated with a local entrepreneur and larger-than-life fellow named Earl Erdner, who died in 1986 at age 78.

Beginning in the 1940s, Erdner had 22 such buildings, many called canhouses, built throughout the county, several of them adorned with adages, according to Ober.

Erdner, who once won a farm in a card game, was a triple-married bon vivant who favored Cadillacs, collected replicas of elephants (trunks facing upward only), and threw lavish Christmas parties for his employees, according to people who knew him. He was director of the Woodstown National Bank and, in 1949, was elected to a single term as mayor of Swedesboro, Gloucester County.

But Erdner’s main job was as an agricultural broker who would contract with farmers in the area to grow crops such as carrots or asparagus, which he would store in one of his warehouses. He’d then sell the produce to Campbell Soup Co., Green Giant, or other large food companies, said Ober, who personally knew Erdner.

For companies such as Del Monte Foods and Heinz, Erdner would store many of their cans of vegetables to later be sold — hence, the “canhouse” label on some of the buildings, said Erdner’s son, Larry, 86, who lives in Pilesgrove.

It was Erdner’s idea to emblazon his warehouses with the profundities of his time, Ober said. “I asked him, ‘Earl, where’d you get those sayings?’ He said people gave them to him. His rule was, ‘If you do business with me and hand me a saying, I’ll just put it on the wall.’”

Larry said his father assigned an art teacher from Bridgeton, Cumberland County, to paint the maxims on the buildings every summer. “It was a full-time job, and he’d keep coming back to repaint them,” Larry said.

Ober said he’s tried to maintain the old chestnuts in their original condition, but “it costs a fortune to go over every letter with black paint.”

Most of the Erdner pearls in the Woodstown grouping are exhibited on three buildings operated by Helena Agri-Enterprises, an outfit that helps farmers improve productivity.

While the dictums are products of a bygone era, the idea of roadside messaging hasn’t gone out of style.

Throughout the country, eager communicators use signs and billboards to attract attention, or to merely amuse.

Outside a community center in Indian Hills, Colo., a volunteer named Vince Rozmiarek places drive-by groaners on an old-fashioned signboard, one letter at a time: “Due to the quarantine I’ll only be doing inside jokes.”

“My mood ring is missing and I don’t know how to feel about that.”

“I call my horse Mayo and sometimes Mayo neighs.”

Communication aimed at travelers has deep American roots, as evidenced by the Mail Pouch tobacco ads painted on the sides of road-facing barns across 22 states for more than 100 years (1891 to 1992), including in Morris County, N.J., and Erie County, Pa.

And drivers from 1925 through 1963 used to speed-read Burma-Shave signs along the highway, so iconic they’re part of the Smithsonian Institution: “Does your husband / Misbehave / Grunt and grumble / Rant and rave / Shoot the brute some / Burma-Shave.”

So far, the Smithsonian hasn’t come calling to preserve the fast-vanishing witticisms left out in the Woodstown weather. Neither have any universities, corporations, or arts organizations stepped up.

“I’ve been thinking about that,” said Vassaras. “I wish they would have kept it up. It was a good look.

“And people could have kept saying, ‘Woodstown, yeah. That’s the place where the sayings are.’”