Dick Allen, finally, could be Phillies’ next Hall of Famer | Extra Innings

Just like an Allen homer over Connie Mack Stadium’s Coca-Cola sign, there should be no doubt that he’s a Hall of Famer.

Nine more weeks. That’s how far we are from opening day. But first, the Phillies have to get to Clearwater next month for spring training, play 32 exhibition games, and trim their roster to 26 players. By the time Joe Girardi’s Phillies get to Miami on March 26 to open the season, we should have a better idea of the team’s playoff chances. Right now, it appears there’s still some heavy lifting needed to be done.

You’re signed up to get this newsletter in your inbox every Thursday during the Phillies offseason. If you like what you’re reading, tell your friends it’s free to sign up here. I want to know what you think, what we should add, and what you want to read, so send me feedback by email or on Twitter @matt_breen. Thank you for reading.

— Matt Breen (extrainnings@inquirer.com)

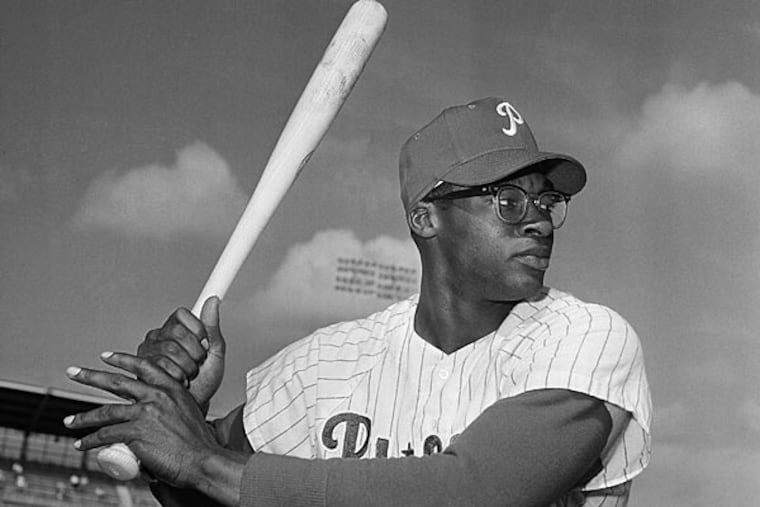

It’s time to send Dick Allen to Cooperstown

When the president of the Pro Football Hall of Fame called Harold Carmichael last week to tell the Eagles great that he was finally being inducted, Carmichael was lost for words.

“I never thought this would happen,” Carmichael said after catching his breath.

It was a great moment for a Philadelphia sports legend who was too often overlooked. The Hall of Fame, finally, righted its wrong. Now, it’s baseball’s turn.

Dick Allen, who should have been enshrined in the 1980s just like Carmichael, is expected later this year to have another chance to reach baseball’s Hall of Fame. The Golden Days Committee will meet in December, and Allen will likely be on their ballot.

The committee consists of 16 members, and a candidate must earn 75% of the votes to join the 2021 Hall of Fame class. It last met in 2014, with Allen falling one vote shy of going to Cooperstown. The Phillies, after this year’s voting results were announced Tuesday, will not have a Hall of Famer this summer. But they could next year if Allen’s luck changes.

Allen played 15 seasons, was a seven-time All-Star, led his league in OPS four times, hit 30 or more homers six times, had six seasons of 90 or more RBIs, was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1964 with 29 homers for the star-crossed Phillies, was the American League MVP in 1972 with a 199 OPS+, and finished his career with a .292 batting average.

He was baseball’s best hitter over the first decade of his career, as Allen’s 165 OPS+ from 1964 to 1973 led the majors, better than all-time greats such as Hank Aaron, Harmon Killebrew, and Willie McCovey. Allen should have become a Hall of Famer in 1983, but he received just 14 votes from the baseball writers and was removed from the process for a year after being named on just 3.7% of the ballots.

The writers likely kept Allen off their ballots in 1983 because of his reputation for being dysfunctional. Among the instances were the injury he suffered when pushing his car, the doubleheader he spent at the horse track, and the time he went AWOL at the end of the season because the Phillies were leaving Tony Taylor off the postseason roster. It was probably those same incidents that kept Allen out in 2014.

Allen wasn’t perfect, but if his shortcomings will be held against him, then what he overcame cannot be ignored. He faced racism as a minor leaguer in Little Rock, Ark., and then broke into the big leagues as one of the Phillies’ first African-American stars during a summer of severe racial unrest in Philadelphia. Allen’s career started with turmoil, yet he still became one of the best hitters of his generation.

Just like an Allen homer over Connie Mack Stadium’s Coca-Cola sign, there should be no doubt that he’s a Hall of Famer. It’s time for Dick Allen to have his Harold Carmichael moment.

The rundown

The Phillies were busy this week signing veterans to minor-league deals with invitations to spring training. Neil Walker has a chance to leave Clearwater as one of the team’s final bench players.

They also signed Francisco Liriano on Tuesday, and the left-hander will compete for a spot in the team’s bullpen. The former starter moved last season to the 'pen and had a strong season with Pittsburgh.

A day earlier, the Phillies took fliers on Drew Storen and Bud Norris. The veteran relievers did not pitch in the majors last season, but they do have major-league track records and will have a chance to crack the roster.

Curt Schilling fell just short this year of reaching Cooperstown, but Bob Brookover writes that the former Phillies ace will eventually get in and makes a case for why Schilling is worthy.

Important dates

Tonight: Phillies Winter Caravan heads to Allentown, 6:30 p.m.

Feb. 11: Pitchers and catchers report to spring training.

Feb. 17: First full-squad workout in Clearwater, Fla.

Feb. 22: Phillies open Grapefruit League play at Tigers, 1:05 p.m.

March 26: Opening day in Miami, 4:10 p.m.

Stat of the day

If Neil Walker makes the Phillies out of spring training, it will erase one headache for the team’s pitching staff. Walker’s .972 OPS against the Phillies was the fifth best among players last season with at least 50 plate appearances against them. He had seven extra-base hits against the Phillies last season and has a career .889 OPS at Citizens Bank Park, Walker’s third highest among NL parks.

His 11 career homers against the Phillies trail only the 13 he has against the Cubs and Brewers. Signing Walker is one way to make sure he stops crushing your pitchers.

From the mailbag

Send questions by email or on Twitter @matt_breen.

Question: I know that sign stealing has long been a staple in MLB but can you explain how a stolen sign can get relayed from an outfield camera to someone else and then to the batter before the pitch arrives. I am 73, still love baseball from the days at Connie Mack Stadium, and have been a longtime (and often suffering) Phillies fan and cannot for the life of me understand how it is accomplished in time to help. — Bill T.

Answer: Thanks, Bill. Would love to hear what you think about Dick Allen’s Hall of Fame case.

For the sign stealing, the Astros had a camera set up in center field that was zoomed in on the catcher’s fingers. A TV was set up outside the dugout that displayed what the camera was filming. When the catcher put down a sign, someone watching the TV then immediately alerted the batter — sometimes by banging on a trash can — what pitch was coming. It had to happen pretty fast, but the Astros found a system that worked.