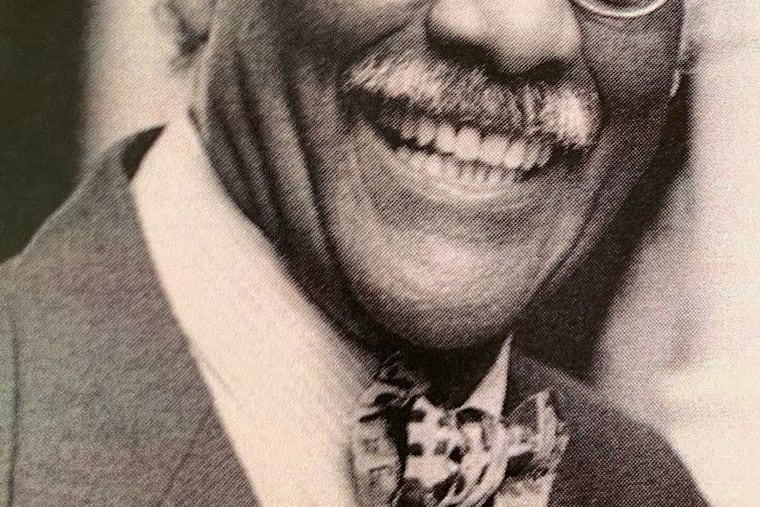

Harold J. Haskins, Penn administrator who mentored African American students, dies at 85

Mr. Haskins started out as a gang worker in North Philly. His successes helped vault him to a prominent post at Penn, advocating for and supporting Black students.

Harold J. Haskins, 85, of West Mount Airy, an educator and activist who mentored young people, first by working with gangs in North Philadelphia and later as a senior administrator at the University of Pennsylvania, died Wednesday, Aug. 5, of pneumonia at Lankenau Medical Center.

“Hask,” as he was known, was appointed Penn’s associate dean of students in 1973. At that time, very few African American students were enrolled.

Mr. Haskins found a low retention rate, anger, and isolation among the few Black students who did enroll. He set out to increase admission of Black students at Penn and to create programs supporting them socially and academically.

“Over the 34 years of his tenure, Hask was truly a master in recruiting, counseling, mentoring, guiding, and literally saving many of these students to assure their graduation,” said his wife, Yvonne. “Hask’s mantra, ‘What is good for Black students is good for all students,’ is in lockstep with ‘Black Lives Matter.’”

Born and raised in West Philadelphia, he attended grade school in the heart of the Penn campus and graduated from West Philadelphia High School. He earned a bachelor’s degree in public administration from Temple University and a master’s degree in city and regional planning from Penn in 1975.

Although he and his wife, who married in 1969, reared their family in West Mount Airy, the Penn campus always felt like home. He likened its students, faculty, and administrators to an extended family.

In the 1960s, Mr. Haskins became known for his uncharted, creative work with street gangs, mostly in North Philly. In 1966, he received a small grant to produce a film. He involved members of the 12th and Oxford Gang in the project.

“Hask hired a filmmaker at a local TV station who spent months with the gang, teaching them in-front-of and behind-the-camera skills,” his wife said.

The result was The Jungle, depicting gang life. The story was written and acted out by gang members, who also composed and performed the music.

The film gained national attention. When there was a request for a screening beyond Philadelphia, Mr. Haskins made sure that gang members presented the film. Most of the young men had never traveled outside their neighborhood, Yvonne Haskins said.

The Jungle won an Italian film festival award in 1968 and was accepted into the Library of Congress in 2009 as part of a sociological study of teenagers in gangs. University sociology departments used the film in their curricula, his wife said.

In 1969, ABC featured Mr. Haskins as an urban trailblazer in a documentary, Three Young Americans in Search of Survival.

“Hask was as much a master with gang kids as he became with his kids at Penn,” his wife said. “He treated them with love and respect, and had high expectations for all the young people he counseled and supported.”

Once at Penn, Mr. Haskins pushed for programs to combat social isolation and the achievement gaps caused by racism, his wife said. He received the support of university presidents Sheldon Hackney and Judith Rodin.

He created a program bringing freshmen to campus a week early for seminars; a tutoring center staffed by Penn graduate students; a program to acquaint high school seniors of diverse backgrounds with the business world; and a Black male support group.

Mr. Haskins also cultivated ties in corporate America to boost the chances of Blacks being hired after graduation. He remained close to many graduates.

“A great deal of Mr. Haskins’ work, from encouraging students’ academic growth to nurturing their leadership dexterities, is immeasurable,” the UPenn Black History Project wrote in 2013.

When not engaged at Penn, the 6-foot-7 Mr. Haskins — known for wearing bow ties — enjoyed ice skating, listening to jazz, playing baseball, and socializing. “He loved being out and about,” his wife said.

Besides his wife, a real estate lawyer and civic activist, he is survived by a daughter, Kristin Haskins Simms; and a grandson. Stepsons Randall and Russell died earlier.

Plans are pending for a memorial event next spring during alumni weekend at Penn.