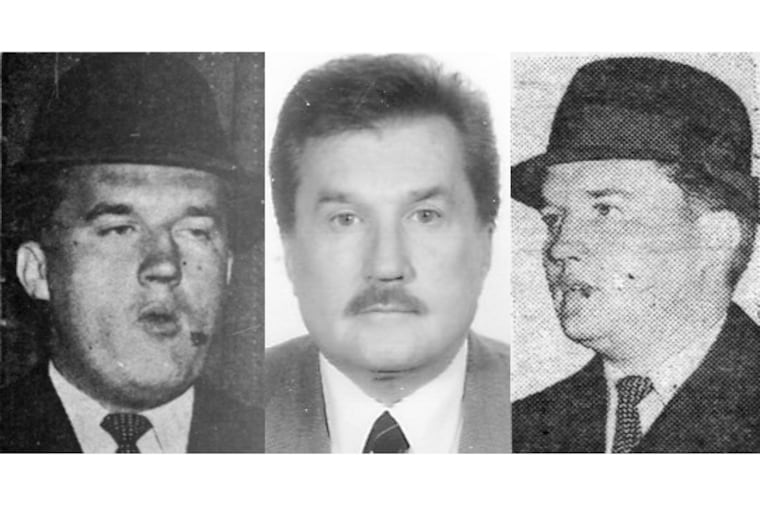

John Berkery, an infamous Philadelphia underworld leader, has died at 91

Berkery became a legend after the 1959 “Pottsville Heist.” By the ’80s, his exploits expanded into a lucrative drug operation.

John Carlyle Berkery was one of Philadelphia’s most clever, charming, stylish, cunning, and fascinating criminals.

With a combination of luck, wit, and smarts, he was often able to escape the grips of law enforcement. Over and over again.

And he loved to taunt and outrun the feds.

In the 1950s, the beefy 6-foot-1 Berkery went from running a bar near Kensington and Allegheny Avenues to becoming a leader of the K&A Gang, also known as the Northeast Philly Irish Mob. They started with burglaries and gambling but by the early 1980s had expanded into a lucrative drug operation.

Berkery, who years later would become a paralegal, has died. He was 91. His widow, Linda Nolan Berkery, said his family has no comment and his death is private. A nephew, Joe Berkery, is the senior multiplatform editor for The Inquirer.

Author Allen Hornblum, who was sued by Berkery for libel, described him as a “very ballsy, aggressive, astute, [and] cutting” boss who resented being considered a criminal.

“He was just a larger-than-life figure,” Hornblum told The Inquirer on Sunday. “So many of these other criminals … either went to prison for years and decades or were killed early, and somehow Berkery escaped all that.

“It was absolutely remarkable.”

Berkery became a legend in 1959 when he was accused of being one of the ringleaders of the “Pottsville Heist,” a burglary of coal baron John Rich’s house in which authorities said $475,000 in cash — worth about $5.2 million today — was stolen. Rich, however, said under oath that he lost only $3,500 in cash and $17,000 in jewels.

Before the case was closed, two brothers — one a participant in the burglary and the other a government witness — were murdered and another participant was shot.

Berkery was the prime suspect. He was questioned but no charges were filed against him in those deaths.

He was, however, convicted of the burglary and was sentenced to 5 to 12 years in prison. He was ultimately granted a new trial and was never retried. He got his record expunged.

By 1963, Berkery was dubbed Philly’s “number one criminal” by then-Philadelphia Police Capt. Clarence Ferguson.

When an Inquirer reporter asked Berkery in 2006 about the heist, he replied, “I don’t know if it happened. If it did, I didn’t do it.”

He had close ties to Philadelphia crime boss Angelo Bruno and roofers union boss John McCullough. When he married for the second time in 1978, McCullough was best man; Bruno was an invited guest. And when he had a baby, Frank Sindone, a Bruno lieutenant, was made the godfather.

In January 1982, he, along with 37 others, were indicted for running a major methamphetamine drug ring. A dealer turned informant admitted setting up an international smuggling ring that brought phenyl-2-propanone (P2P), a key ingredient to manufacture speed, into the country.

They were charged with conspiring to distribute enough P2P to manufacture millions of dollars worth of methamphetamine.

But Berkery, who used to live in the 11000 block of Dora Drive in Northeast Philadelphia, fled before he could get cuffed.

For five and a half years, he kept the authorities on their toes and seething with frustration. They chased reports that he had been spotted in Wildwood, N.J., Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Canada, and elsewhere.

With disguises, aliases, and various passports, Berkery flitted from Miami, Honolulu, San Francisco, Ireland, England, and the Bahamas and back again.

He was on the lam in February 1982 when he filed suit against the Internal Revenue Service to get access to his Irish bank accounts, tied up for alleged back taxes.

And he liked to play in a Catch Me If You Can style.

In 1984, he wrote to a prosecutor for the U.S. Organized Crime Strike Force, seeking to return to Philadelphia and plead guilty to reduced charges in exchange for a three-year prison sentence. He even complained about not liking the weather in Ireland.

“I’ve been gone for the better part of three years, the equivalent of a five-year sentence, at my own expense, just to try to get a fair deal,” Berkery wrote. “What is so wonderful about that? If the situation were reversed, being a prudent man, do you honestly believe you wouldn’t have done the same thing? And at least you’d be in sunny Italy. Here I am with an umbrella and a hot-water bottle.”

“What are we proving?” he continued. “I’m sure the crime rate didn’t go down since I left. Be reasonable … . Gimme a break, Mr. P. I’m starting to feel like the poor man’s Robert Vesco.”

The prosecutor refused the deal.

The cat-and-mouse game ended in June 1987 when the FBI and U.S. Customs agents arrested Berkery outside Newark International Airport.

The next month, he stood trial on federal drug charges that could have brought him up to 70 years in prison. He was sentenced to 15 years.

But in January 1989, the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals threw out the drug-dealing conviction on the basis of a legal brief that Berkery wrote by hand in his federal penitentiary cell in Alabama.

He argued that a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court the year before changed the law in cases where defendants claim they have been entrapped. Berkery wrote that that should apply to him because he had been entrapped by an FBI informant. The judge agreed with him and overturned his conviction. He won a new trial, but instead opted for a plea deal.

Ronald Kidd, the lawyer who represented Berkery at his trial, had said Berkery mailed the brief to his office, where it was typed and packaged.

“The credit’s all his. If I had done it, we probably would have lost,” Kidd said at the time. “This will just add to the folklore of John Berkery.”

Berkery was never one to stay silent if he didn’t like what was said or written about him. In March 1990, he wrote a letter to the editor of the Philadelphia Daily News, criticizing an article about his plea agreement.

“How do you justify the phrase ‘considered to be one of Philadelphia’s arch-criminals,’ when I haven’t been in Philadelphia for over eight years (and don’t intend to return)?” he wrote.

”From 1962 to 1987, a period of 25 years, much of which time I was under constant investigation, I was never charged with, much less convicted, of a crime (except for an assault and battery at a private home and a ridiculous little bribery case in Delaware County of which I was speedily acquitted, hardly the activities of a ‘seasoned professional’),” he continued.

He praised his notorious friends, too: “I found Angelo Bruno a man of honor and integrity and a true ‘gentle man’ in the literal two-word context. That opinion was formed over 25 years ago, although we never made 25 cents together or had business dealings.”

And he said he had become a changed man. A better man.

“By the time I was arrested, I had become such a law-abiding citizen that for the six years I was a fugitive, I never so much as spit on the sidewalk. It felt good that way. All my old friends are dead and my loyalties no longer required. I’ll try to make friendships that are easier to live with, for my family’s sake.

“I have had the courage to admit my guilt and am sorry for what I did. I always thought that should count for something.”

In 2006, he took issue with Hornblum’s book, Confessions of a Second Story Man: Junior Kripplebauer and the K&A Gang.

In it, Hornblum, who served on the Pennsylvania Crime Commission and the board of the Philadelphia Prison System, described Berkery as a key player in the city’s methamphetamine business, and “the main nexus between the Northeast Irish mobsters and the Mafia.”

Hornblum said on Sunday that Berkery — who briefly went to law school — was litigious and used lawsuits as intimidation.

“He just wasn’t a thug who would walk into a convenience store and threaten the manager or teller,” Hornblum said. “He would try to think of some sophisticated white-collar schemes where he could come up with big cash.”

In a $10 million libel suit, Berkery called Hornblum a “reckless researcher and a proven liar,” and said the author lied about him in the book.

In 2010, a New Jersey appeals court ruled that Hornblum did not defame Berkery by writing about his alleged gang activity decades ago.