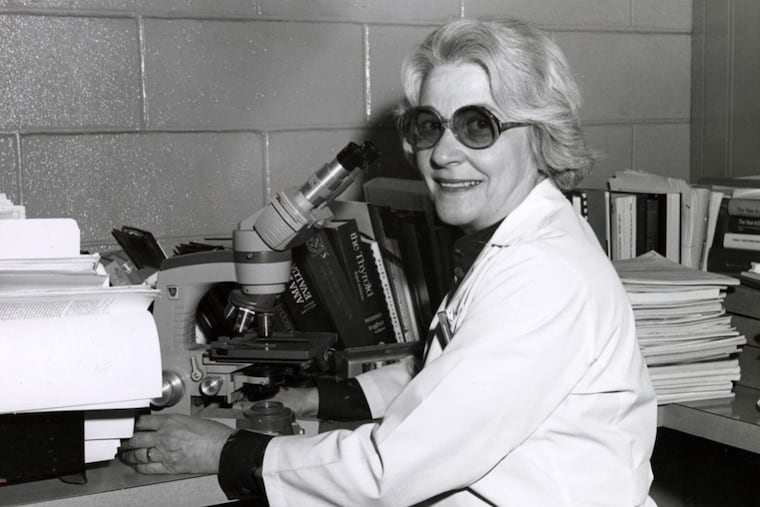

Mary B. Dratman, renowned research scientist and longtime medical school professor, dies at 101

She not only did important research in endocrinology, how thyroid hormones affect the brain, she inspired other women to become scientists, doctors and professors.

Mary B. Dratman, 101, formerly of Philadelphia, an internationally celebrated research scientist, versatile clinician, and longtime medical school professor at the Medical College of Pennsylvania and the University of Pennsylvania, died Thursday, Jan. 13, of heart failure at Lions Gate retirement community in Voorhees.

Focusing on endocrinology, specifically how thyroid hormones affect the brain, Dr. Dratman spent nearly 70 years in laboratories, hospitals, lecture halls, and classrooms in Philadelphia, Paris, and elsewhere around the world.

She was founding director of the division of endocrinology in the department of medicine at Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in the 1960s and chief in the 1970s of the endocrinology section at the Medical College of Pennsylvania, both of which are now part of the Drexel University College of Medicine.

She studied obstetrics and gynecology, and in 1978 became a professor in the department of medicine at the Medical College of Pennsylvania. She was an adjunct professor in 1984 in the departments of medicine and psychiatry at Penn’s school of medicine and also worked for Veterans Administration medical centers and the Rockefeller University.

She lectured about her research across the country and in Japan, Africa, Europe, and elsewhere; published dozens of book chapters, journal articles, and research papers about the endocrine system and other medical topics; and received half a dozen awards, including the 2013 Women in Medicine Award from the Drexel University College of Medicine.

Along the way, Dr. Dratman supported liberal political causes, was an early proponent of abortion rights, and, according to peers and former students, paved the way for others to follow her professional path.

“Her prolific and cutting-edge career was a groundbreaking model for the role of women in science,” said Joseph Martin, an emeritus professor of biology at Rutgers University and one of Dr. Dratman’s many coauthors.

“Women looked up to her,” said her son, Ralph.

A year ago, at 100, Dr. Dratman published the last of her scholarly articles and was still attending monthly book club meetings. She “embraced life with a passion and vigor I have rarely seen,” a friend wrote in a tribute.

In 2006, Dr. Dratman cowrote a paper that may have explained in part why she was drawn to research and its clinical applications. People needed it. “Many lines of evidence indicate a role for thyroid hormones in the expression of cognitive and affective disorders,” the authors wrote. “These conditions constitute a large proportion of the illness burden in the general population.”

Born July 4, 1920, Dr. Dratman grew up in Strawberry Mansion in a Yiddish-speaking home. She graduated from Philadelphia High School for Girls, earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry at Penn in 1940, and got her medical degree from Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1945 after quotas for women and Jewish students kept her out of Penn’s medical school.

She married Mitchell Dratman, a psychoanalyst and psychiatrist, in 1946, and had son Ralph and daughter Victoria. They lived in Mount Airy and Chestnut Hill, and she later moved to Cherry Hill and then Voorhees about three years ago. Her husband and daughter died earlier.

Away from the labs and hospitals, Dr. Dratman hosted chamber music concerts and Broadway tune sing-alongs at her home. She studied French and Chinese cooking and traveled with her family to the wilds of Connecticut and the French Alps.

For years, she met every week with Frank Sterling, an endocrinologist colleague and friend, to read books about biology and then hash over each point. Her surviving papers are kept at the Drexel College of Medicine’s legacy center.

“She took an interest in what other people had to tell her,” said her son. “She had a genuine interest. I’d say she was quietly gregarious.”

A friend wrote that Dr. Dratman “had an extraordinary life force, and was beloved by family, friends, and generations of students.”

In addition to her son, Dr. Dratman is survived by a grandson, a great-grandson, and other relatives. Two sisters, two brothers and a granddaughter died earlier.

Services were private.

Donations in her name may be made to Planned Parenthood Federation of America Inc., Attn: Online Services, P.O. Box 97166, Washington, DC 20090.