At the border, fear and uncertainty as Trump seeks to remake the immigration court system

In immigration courtrooms across the country, ICE agents stand in wait to arrest people who are following the rules.

EL PASO, Texas — A small group of immigrants gathered in the lobby of the Richard C. White federal building downtown here on a cool early morning in November. They waited to be allowed up to the seventh floor, where they would appear before a judge as their case made its way through the immigration system.

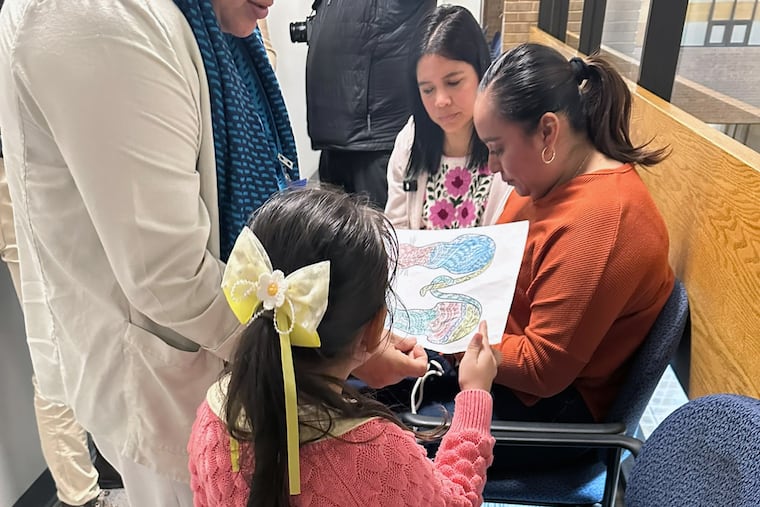

Among them were Noemi and her 6-year-old daughter, Abigail. They had driven more than four hours to get to their court date and were hoping to head back the same day. While Noemi was soft-spoken, Abigail was sharp and spirited, more than willing to answer all the questions she was being peppered with by strangers.

She spoke about where she was from (El Salvador), her favorite show (Bluey), about school (It’s all right), and about her older best friend (She’s 8).

Abigail has been in the U.S. since 2021, arriving with her mother in search of a better life. They were welcomed by a Biden administration that, despite its many faults, initially asserted an immigration policy that was deeply humanitarian.

But that was then.

While the immigrants sat and waited, Sigrid González introduced herself. She was a volunteer doing court accompaniment. They could not offer legal advice but were there to observe and help immigrants plan — did they bring a car? Do they have kids in school? Do they know whom to call? — in case they were detained.

“ICE is here. They have a list. We don’t know who they will take,” González said. “This is not to frighten you, but to let you know.”

Later, as the elevator doors opened on the seventh floor, a group of about half a dozen Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents were indeed there. Dressed as civilians but still in uniform: blue jeans, sneakers, and dark jackets.

El Paso has not seen the kind of excessive use of force seen in places like New York, but as in immigration courtrooms across the country, ICE agents stand in wait to arrest people who are following the rules.

The government’s strategy is to ask the court to dismiss an immigrant’s case, making them eligible for expedited removal, a relatively quick process under which a noncitizen can be deported back to their country, potentially without any additional immigration court hearings, Emmett Soper, a former immigration judge in Virginia, told me.

In practice, however, ICE agents regularly detain immigrants regardless of a judge’s decision on dismissal.

“I denied every single motion to dismiss. I set the case for a further hearing. I gave all the required advisal, things like that,” Soper said. “Every single person was arrested, to my knowledge, after I denied the motion to dismiss.”

The Trump administration is not stopping at ignoring due process, it is also working to reshape the immigration court system. Soper is one of about 100 immigration judges fired this year. There is no explanation for the dismissal of the judges, other than many of them having a record seen as out of step with the administration’s hard-line approach.

Instead of an experienced jurist like Soper, who took the bench in 2017 and understands that every case should be given a fair hearing according to the law, Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem is looking for people who want to be a “deportation judge” and want “to restore integrity and honor to our Nation’s Immigration Court system.”

In case there was any doubt what the Trump administration wants to restore, DHS clarifies in a recruitment ad: “Defend your communities, your culture, your very way of life.”

As Abigail sat next to her mother inside Judge Judith F. Bonilla’s courtroom, coloring an image of two cats sitting side by side handed to her by the court clerk, it was hard to see what the White House is so afraid of.

Noemi was so concerned about her legal case that she would only speak with me on the condition that her last name not be used. She did not have a lawyer. The judge asked her a series of questions and she responded in turn: She had no family in the U.S., she had not been a victim of a crime, it was her first time in the country, she had never been arrested. She was not afraid to go back to El Salvador.

It was clear from her answers that Noemi did not want to fight her case.

The only relief available for her, the judge said, was voluntary departure. If she took that option, Noemi waved her right to appeal but it left the door open for them to return legally in the future.

“I want voluntary departure,” she said.

Noemi and her daughter had 90 days to leave the U.S.

Outside the courtroom, Noemi met with González, who asked her if she wanted to share any contact information in case they were detained by ICE. Noemi looked confused.

“I have voluntary departure; can they still take me?” she asked. Based on experience, González did not hesitate to answer: “Yes.”

I have been thinking for weeks about Noemi’s face at that moment. How to describe what it looks like when someone who has gone through the legal process and made peace with the fact she cannot stay in the U.S. must still face the random cruelty of an administration that sees her and her 6-year-old as a threat.

Crestfallen, Noemi shared her information with González.

Across the hall, the ICE agents began to move toward the elevator. Apparently, they were leaving. Everyone around Noemi and Abigail sighed in relief. The mother and daughter were not among those taken, which that day included a man and a mother and her older son.

As Noemi and Abigail left the federal building to drive back home through the west Texas desert — back to the life they had built for themselves over four years and now had 90 days to leave — the only thing I could think was, how does this benefit America?

More from the border: Trump may have shut down the border to asylum-seekers, but he can’t end immigrants’ hope