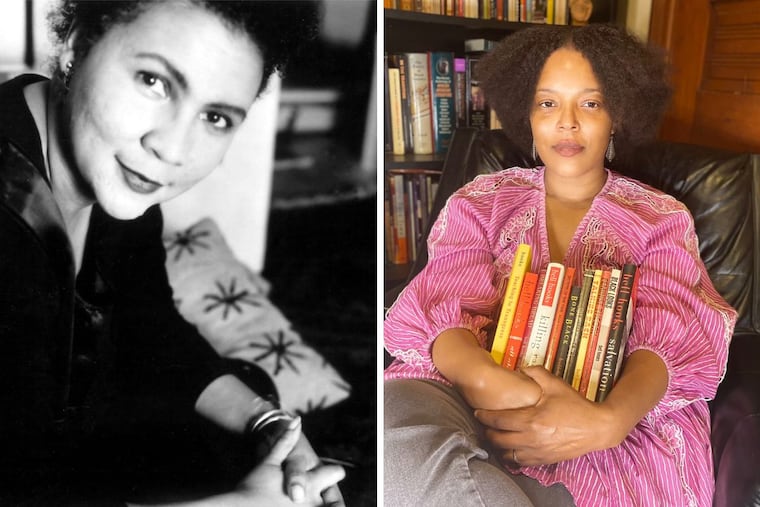

bell hooks and me: How this acclaimed Black writer taught me to value everyday moments | Opinion

Poet and teacher Yolanda Wisher on the legacy of bell hooks, who died this week at age 69.

bell hooks shaped me. She wasn’t on the shelves of my mother’s bookcase, not with Alex Haley’s Roots or Stephen King’s horror tales. Instead, I found bell hooks when I left home. And I’m so grateful I did.

hooks, the great Black feminist writer, professor, and activist also known as Gloria Jean Watkins, died on Wednesday, at age 69, in Kentucky, where she was born, prompting me to reflect on the impact she had on my life.

I went to a predominantly white college in Pennsylvania to play basketball. But I quit playing after a year because I discovered that I’d rather be a writer. Around that time, hooks’ work started to pop up in my English and Black studies classes. For me and so many others, a bell hooks essay in a photocopied course packet was homework gold. It could literally change your life, momentarily cure you of self-hate and imposter syndrome.

I started to collect her books with the little bit of money I earned as a work-study student. First was Sisters of the Yam: Black Women and Self-Recovery, in which she talked about topics like hair, mental well-being, stress, and addiction. A child of working-class folks like me, hooks guided me through the underbelly of undergraduate and graduate school, which I often experienced as an assault on the core of being in a Black woman’s body and a constant reminder of how little that body and my voice were valued on the world stage. Like her, my folks were janitors, maids, and caretakers, essential workers before they were called essential. And like me, hooks had a great-grandmother who imbued her with a sense of pride and possibility.

» READ MORE: Four Philly poets share their perspectives on ancestral Blackness

And Dr. bell hooks was a real scholar who had made it through the gauntlet of higher education and survived to tell about it in her words, with her own sharp tongue intact. If she could do it, I could too, I thought.

In Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, she wrote: “The most powerful resource any of us can have as we study and teach in university settings is full understanding and appreciation of the richness, beauty, and primacy of our familiar and community backgrounds.” Here was a scholar who — rather than drifting from home — seemed always to be writing toward it. She had this way of making an essay about the complexities of history, culture, art, or politics incredibly personal and down-to-earth. She seemed to say: The lives and lessons of the people we come from matter. Their stories are the material. Like literary foremothers Zora Neale Hurston and Toni Cade Bambara, she made people the center of her business. She didn’t leave her life behind; instead she talked about a home not unlike the one that I was busy running from.

When I started teaching high school English after grad school, it was to her book Teaching to Transgress that I turned to challenge my work to be more than lectures, vocab quizzes, and multiple-choice tests. In that text, she uplifts the words of Thich Nhat Hanh, who describes what it feels like to be in the presence of a great teacher. He says that such a teacher can “bring that milieu. ... It is as though you bring a candle into the room. The candle is there; there is a kind of light-zone you bring in. When a sage is there and you sit near him, you feel light, you feel peace.”

bell hooks was that kind of teacher. Even though I never met her, her light reached me through her words. In more than a few of her 30-plus books, hooks was documenting the journey of someone deeply called to teach in the most wholehearted and responsible way possible. I aspire to that whole-hearted work every time I step into the classroom and come to the page. And when I see other people reading her words on the bus, in coffee shops, or posting quotes of her work on Instagram, I understand the power of a light that allows you to see your own more clearly.

This evening, I revisited my love for bell hooks, looking for lines that I read years ago and felt the need to underline or highlight. These are my footprints as a student of hooks. I came across my hardcover copy of Salvation: Black People and Love, and I think this might be my favorite because my partner gifted it to me for a birthday back in the day. The red ink he used to inscribe it is near invisible on the red cover page. As I turned the pages, I discovered a picture of us from 1999, the year we met while I was in grad school at Temple University. We’re sitting in the grass in a park in Philly, his head is in my lap, and we are smiling mischievously. It was tucked in there between pages 186 and 187 along with a ticket stub from a plane trip we took, probably our first.

This book, beloved for too many reasons, is what a bell hooks book does — invites our whole selves in and holds us there in a history of the world that will always require the footnotes of families and the marginalia of everyday life.

Yolanda Wisher is a poet, bandleader, and educator. She is the curator of spoken word at Philadelphia Contemporary.