America needs a GI Bill for health-care workers | Opinion

The program would not only help our health-care workers but also our civic infrastructure —w hich could use a little help right now.

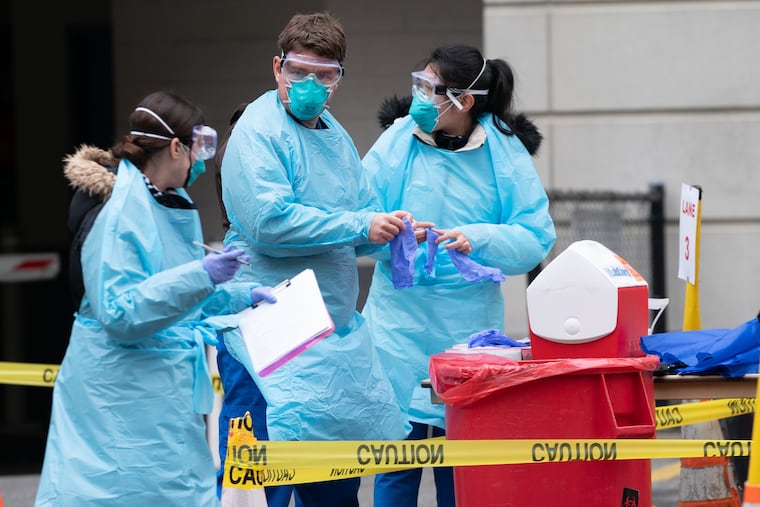

Our frontline health-care workers are heroes, every bit as much as our military members. In recognition of their dedication, selflessness, and sacrifice we should establish a program of educational support for them similar to the GI Bill. This program will invest in a group of people who have independently decided to serve us. What better investment than an investment in the people who have dedicated their professional lives to keeping us healthy? The program will not only help our health-care workers but also our civic infrastructure — which could use a little help right now.

The GI Bill was the single most effective piece of post-World War II public policy. The GI Bill sent a generation of Americans to college who could not otherwise have afforded it. According to the Veterans Administration, 2.2 million veterans used the program after World War II to attend college and an additional 5.6 million received vocational training — this out of a total of approximately 11 million eligible veterans — a 51% take rate. In so doing it created the modern U.S. economy.

The GI Bill’s primary virtue was its egalitarianism; in an age when most expected to live the lives their fathers did, the GI Bill changed everything. The program has been updated several times since its inception. As of January 2019, $12 billion of educational benefits have been provided to over 800,000 veterans or family members. Just as important, the GI Bill is a tangible demonstration of the nation’s gratitude in a way that benefits the nation and the individual veteran — a win-win scenario on a national scale.

» READ MORE: From the Front Lines: What scares the people too essential to isolate

Recognizing our health-care workers presents exactly the same opportunity. These professionals are a motivated and talented group who have chosen to serve society. Creating a program like the GI Bill will help them help us by easing the financial burden of education, training, and professional certifications. And, just as the GI Bill works as a powerful recruiting tool for the Pentagon, the new program will attract more young people to careers in medicine and health care.

The program should be permanent — not a temporary thank you for helping us through this rough patch — but a standing statement that, as a society, we value the sacrifices our health-care workers make every day. Program eligibility criteria need to be established and should be based on the public good. One option: to use the program a certain percentage of your medical practice or job should be in the public arena for a certain period of time (to be determined). The program should have three pillars:

Forgive outstanding student debt for health-related education and training.

Cover future expenses for health-related education and training.

Encourage young people to enter the health-care field.

The first pillar will mostly help doctors and nurses who require years of school before they are licensed to practice. But it will also help other technicians and specialists who need advanced training and certifications.

The second pillar can help a medical technician who wants to become a registered nurse or someone working in hospital administration who wants to get an advanced management degree to further their career.

The final pillar will encourage promising high school students to consider a career in health care by covering their education and training. The military has been doing this for years with ROTC scholarships to university students in exchange for a period of service after graduation.

Another provision worthy of consideration is support for immigrants seeking to work in the health-care industry. In the U.S. today 29% of our doctors are foreign born and overall 17% of our health-care workforce are immigrants. Providing an accelerated path to full citizenship for these heroes is certainly low-hanging political fruit.

“The GI Bill made money for the U.S. government, there is every reason to believe a similar program for healthcare workers will do the same.”

Such a program would fit neatly into the existing portfolio of the Department of Health and Human Services. When considering the program’s cost it’s fair to consider cost avoidance. The improved public health outcomes resulting from such a program will be in the billions annually. A 2018 study by the Milken Institute found the annual cost of obesity to the U.S. to be $1.7 trillion; approximately 9.3% of annual GDP. If a GI Bill for health-care workers is able to improve health outcomes in the U.S. by just 20%, it would represent a savings of $3.4 billion every year. The GI Bill made money for the U.S. government, there is every reason to believe a similar program for health-care workers will do the same.

» READ MORE: Inside a Philadelphia COVID-19 hospital, where everything is repurposed toward survival

Our health-care workers are a national treasure we have too long taken for granted. They quietly sacrifice for us every day; the current health emergency has only served to highlight that sacrifice to average Americans. The GI Bill rewarded a segment of our society who sacrificed to serve the greater good. It also set the stage for the largest, most prolonged growth in American history. A program similar to the GI Bill for our health-care workers will have many of the same positive effects on our society. The program should be permanent, flexible, and designed to reward those currently serving in America’s hospitals and care facilities as well as young people pursuing a career in medicine and health care. The GI Bill paid back America’s investment by returning $7 to the economy for every $1 invested in the program. There is every reason to believe a similar program for our health-care workers will deliver a similar return on investment. This is an easy decision. Invest in the best of us.

Col. Curtis Milam has more than 4,000 flight hours in the C-130 and has seen some things.