How I forgave my homophobic evangelical community for hating who I am | Opinion

My church was in the “hate the sin, love the sinner” group of evangelicals, forbidding same-sex romantic relationships.

This year I finished my first year of college. It was the first time in my life that I was truly open about something that used to make my intestines twist into knots. For many of us, “coming out” as gay is not the quick revelation of a Pride parade Instagram post, but a slower process. It takes gasps of courage to motivate an admission that feels like someone taking a spoon and digging at your heart like it’s breakfast cereal, as I awaited judgment and condemnation.

My college acquaintances, close friends, and nuclear family know about my sexuality. But almost no one from the Central Jersey church I grew up in knows. My church was 2,000 bodies strong, a well-oiled evangelical machine that promoted homogeneity. Nearly all the congregants were Chinese American. In finding solidarity with people of like ethnicity, they chose to cling to a conservative form of Christianity that, backed by Confucian gender roles, excluded others. The church was in the “hate the sin, love the sinner” group of evangelicals, forbidding same-sex romantic relationships, deeming them sins. And the official policy of “hate the sin, love the sinner” was often contorted into disgust towards all non-hetersexual or cisgender people.

» READ MORE: Instead of making me straight, joining a church convinced me to come out | Perspective

But despite their hatred of my identity, I think of my departure from my church as a story of love. Because I have forgiven this community.

It wasn’t easy. I have painful memories from my congregation. I remember being in Sunday school at age 14, and the elder lectured us on false prophets and how their followers will go to hell. He showed a picture of two male priests kissing. When I remember this moment even now, I feel my heart sink into my abdomen.

I remember another teacher recalling how disgusted he was to see a church with a rainbow flag. His wife told me, in a private conversation after I responded to an altar call, obscene, filthy, and unholy things about how awful gay people were and how people were only gay because they were raped.

I told myself, never, ever hate those church people. Did I listen to that warning? Of course not, at least not right away. I felt hate toward them for a while, even if it went against my own views of morality. I gave Jesus my soul, and his followers stepped and spat on it.

Yet over time my hate waned. What changed? I started forgiving during my senior year of high school, as the world struggled with the pandemic. The anger and bitterness bit at my heart until I realized they would consume me. So I forgave and forgive.

I forgave and forgive because Earth is crying for more love, and I do not love well nor deeply when angry. I chose to forgive, knowing that it would be difficult, because I was ready for the challenge of compassion when members of the church were not. My heart could only become stronger if I loved more and let go of my anger.

Really, I forgave the homophobes for selfish reasons. I let go of my anger because I’ve never seen a homophobe, racist, misogynist, or any other person with hateful views change because of anger and yelling. I’ve only seen them change through understanding, patience, and love. I think for example of Megan Phelps-Roper, a former member of the hate-speech-spreading Westboro Baptist Church, who left the church after people she connected with on Twitter peacefully challenged her views.

» READ MORE: I feel unsafe in broad daylight because of something I can’t change about myself | Opinion

I have this hope, naïve as it may be, that if my once-fellow church members could see me, really see me, they would recognize the “godliness” of my forgiveness. Then maybe, just maybe, they would reconsider their stance on LGBTQ people. I still have that hope. I’ve forgiven because God has forgiven me for all the mistakes I’ve made as the flawed human I am, so I can forgive my “debtors.” Being presented with an all-encompassing love and compassion gave me the courage to be better than those who despise others. And I believe love is better understood once grounded in the context of pain. Love becomes more resilient when the world tries to beat it down. It must, because the only other option is to fall apart, hollow out, and rot into bitterness.

What I haven’t acknowledged yet is that it takes immense work to forgive — and also the privilege of distance from those you are forgiving, and the ability to rebuild after their hate. Who would blame rape survivors for not forgiving their rapists?

Not everything is readily forgivable, and it is not always a failing to remain in anger. But I learned in my anger that it is important, in that state of mind, to remain anchored in the things you love, because uncontrolled anger is caustic.

I thought hating those who hate me would make me just like them. Our mutual hatred was the reflection in the mirror we shared. But it’s past time to shatter, and rebuild, that mirror.

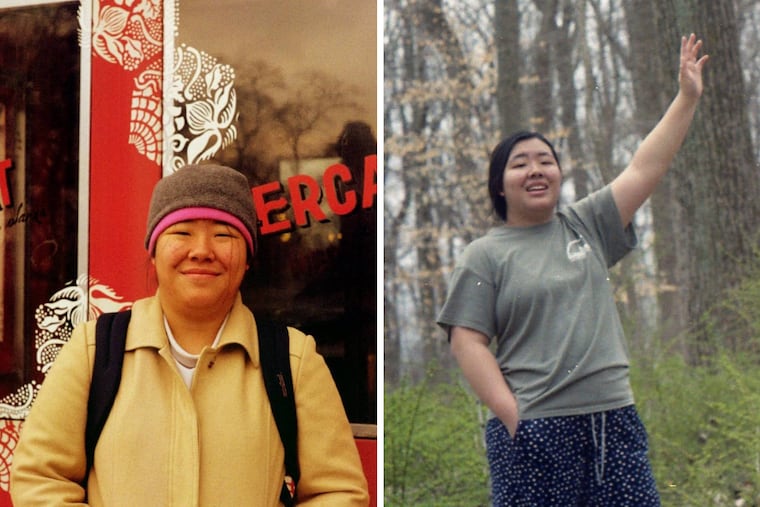

Alicia Liu is a student at Swarthmore College. She likes to write, read, and take pictures.

Read more stories of changed minds

Want to write about your own change of mind or heart? Tell us at opinion@inquirer.com.