Let sick and elderly prisoners like my brother come home | Opinion

My brother has been in prison for 30 years, and now needs a wheelchair and oxygen. He is not a danger to anyone. Let me and my family take the caregiving burden off the state.

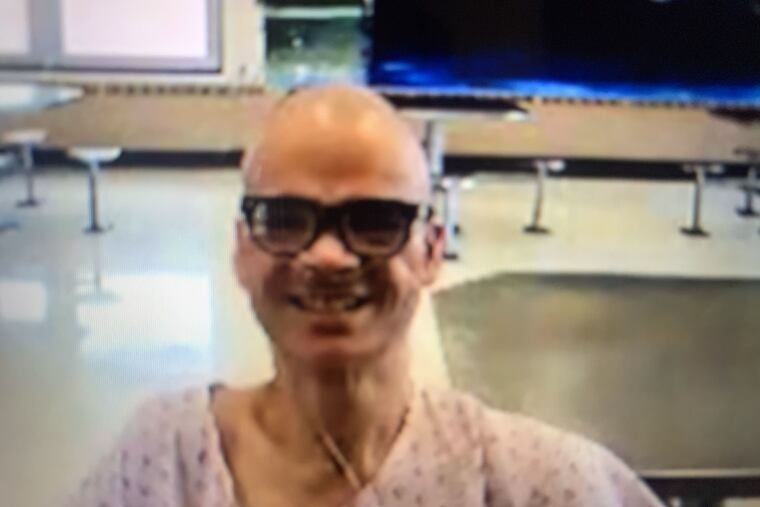

More than one year ago, my best friend and brother, Juan Perez, woke up from a five-month coma. He’d gotten sick with COVID-19 during the early days of the pandemic. He is incarcerated, so he lives at a medical prison, which he navigates in a wheelchair with an oxygen machine.

He is only one of about 1,500 elderly and chronically ill people incarcerated in the SCI Laurel Highlands medical facility in Somerset. Juan tells me about the others — there are people in wheelchairs, amputees, people with schizophrenia. Many of them are there because, like my brother, they have been sentenced to life without parole.

There are more people serving life sentences without parole in Philadelphia County than in any other county in the world. Last month, a bill was introduced in the Pennsylvania House (HB 2347) that would make people who have served long sentences and are sick or elderly eligible to be considered for parole. For thousands of aging people who are incarcerated in Pennsylvania, it is a chance to come home.

“For thousands of aging people who are incarcerated in Pennsylvania, [a new bill] is a chance to come home.”

Juan was in his early 20s when he was locked up for life. He was lacking the things he needed growing up — clothing, transportation to get to school. He started dealing drugs in high school to make money, and dealing went along with using drugs.

My brother was loving. But when he started doing drugs, it affected his mental state. He started selling fake drugs (such as laundry detergent) to make money to support his habit, and one morning one of his customers came back, angry. They fought, and another drug dealer with a gun got involved. That drug dealer ended up killing the angry customer; the state claimed my brother helped, but a witness at my brother’s trial testified that he ran away after the robbery and wasn’t there for the shooting.

While the shooter got the death penalty, my brother was found guilty of second-degree murder and received the mandatory sentence for this offense in Pennsylvania: life without parole. This is how it works in this state — someone who didn’t pull a trigger can be sentenced to life in prison just because they were aware of or involved with a death, even if that death was accidental.

My brother has been in prison for the last 30 years. He has said he regrets his actions, and I believe him. At the time of his crime, he needed rehabilitation and drug treatment, not a life sentence.

Each life sentence for someone convicted at age 25 costs the state an estimated $3.6 million. My brother is now 54 years old. Due to additional health-care needs, it is up to three times more expensive to incarcerate people over 55, who collectively cost our state roughly $86 million per year.

Our legislators should be passing bills to give a chance at parole to people like my brother who are older, sick, and need to come home to their families.

I don’t believe my brother is receiving adequate care at SCI Laurel Highlands; I try to coach him through physical therapy over the phone. The last time I visited him, he had to unplug his oxygen tank to come down the third floor. He was so out of breath that he spent a lot of the visit trying to find an outlet to plug in his oxygen machine. I told him I didn’t even know if I wanted to come back, if it was that dangerous for him. His memory is also starting to fade.

If my brother could come home, I’m willing and able to take care of him. We have reserved one of the bedrooms in our home for him, and have plans to make it handicap accessible. My parents are in their 70s and 80s, and I would love for him to come home while they are still here.

Why are sick inmates like my brother still in prison? These people are aging out of crime — by the time people reach age 65, recidivism rates are less than 1%. They are not a risk to the community. Send them home to their families. Let them have dignity in their final chapter. They cannot work, but at least their family members could care for them, and take the burden off the prison system.

These laws need to change. HB 2347 will help move Pennsylvania forward. (Its counterpart in the Pennsylvania Senate, SB 835, already has bipartisan support.)

My brother has served his time and deserves the right to spend his last years with dignity. Send him — and other sick, elderly inmates — home to their families.

Mayra Skinner is an advocate for prison reform in Pennsylvania. She wrote this in collaboration with Maddie Rose of Straight Ahead.