Hey Mural Arts, graffiti is art, too. It always was.

The Philadelphia organization is rooted in racism and discrimination against local graffiti artists.

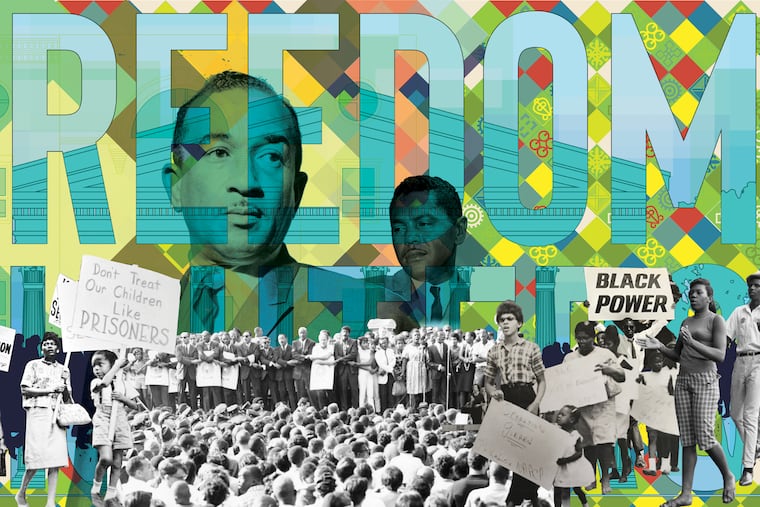

In 2020, in the midst of national protests against the racist systems that led to the murder of George Floyd, Mural Arts Philadelphia quietly announced that it had abandoned its mural of Frank Rizzo, which had long irked local activists and community members. Mural Arts — sponsor of thousands of murals around the city — stated: “We believe this is a step in the right direction and hope to aid in healing our city through the power of thoughtful and inclusive public art.”

Few beyond dedicated fans know the history of Mural Arts. While it’s hard to find someone who doesn’t like the beautiful murals that decorate our city, it’s important to realize that Mural Arts’ success is mired by a legacy of urban racism. That legacy — from Mural Arts’ criminalization of local graffiti artists, to its selection of international submissions over local artists, to its difficulty letting go of the Rizzo mural — impacts art in the city today.

In the 1980s, Black politician Timothy Spencer founded the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network (PAGN). The network was inspired by a Philadelphia Museum of Art program that claimed to rechannel graffiti writers’ energy toward neighborhood murals. Spencer brought the network under the “war on graffiti” in Philly, which was run by Mayor W. Wilson Goode Sr. (of MOVE bombing infamy). According to sociologist Tyson Mitman, under Goode, graffiti went from being a $10 fine to a $300 crime. During this time, the pioneer graffiti writer Cornbread was hired by the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network after bragging that the organization would fail without him, but he left after fighting with Spencer.

The New Jersey-born founder and head of Mural Arts — Jane Golden — began working with the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network under Spencer in the 1990s. When Spencer passed away in 1996, Golden worked with Mayor Ed Rendell to gain private funds to create Mural Arts, causing a split away from the still-living public organization PAGN. Under Rendell, graffiti became a crime punishable by up to a year in prison or a $2,000 fine, a graffiti criminal court was established, and even carrying a spray paint can was a charge of “possessing an instrument of crime.”

For young graffiti artists, their highly stylistic and calligraphic “wickets” were an alternative to gang life in communities abandoned by slumlords and the city. But as scathingly noted by the Kensington Welfare Rights Union in its 1998 tract “The War on Graffiti is a War on The New Class,” the city spent $3 million a year and brought in the National Guard to rid Philadelphia of graffiti.

Under this militarized approach to graffiti, Golden accepted praise for “battling graffiti in the city.” Golden’s work at the PAGN cosigned the city’s stigmatization of graffiti writers as racially coded “gang members,” as seen in the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network’s 1980s promotional video portraying graffiti writers as Black despite their racial diversity in real life. Golden argued that she “saved” young men such as the future artist Black Thought when she would swoop down among those who were serving “scrub time” for Goode and ask them to work for her murals as amnesty. But the question for Golden and Mural Arts is: Why were these punishments present in the first place if not for the Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network that Golden worked for?

Today, Mural Arts is a wealthy city-supported nonprofit that funds the massive Philly murals we know and love. However, Mural Arts’ success has been at the expense of defunding and criminalizing local graffiti artists. Funds are only granted to approximately five awardees yearly out of over 80 applications. Mural Arts has priced out locals while hiring international graffiti artists, such as the European graffiti brothers How and Nosm in 2013.

For Mural Arts to truly be healing our city, it must advocate for a Philadelphia where local artists have more freedom over public spaces. Mural Arts must take a stance against the criminalization of graffiti, especially considering how racist real estate appraisals in Philadelphia consider local unpaid graffiti “vandalism” but paid graffiti murals “art.” Instead of pushing graffiti artists out of public spaces in favor of paid muralists, Mural Arts could be a leader in pushing the city for community-owned public spaces where street art is not policed.

Here’s to Mural Arts — may it grow past its current whitewashed legacy to show us a Philadelphia in full color.

Razan Idris is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Pennsylvania. @idris_razan