Telling a Native story from Native perspectives: Revisiting Pennsylvania’s Conestoga massacre | Opinion

As local indigenous peoples at Circle Legacy Center repeated during our research trips to Lancaster: “We’re still here.”

On a frosty December morning in 1763, a mob of frontiersmen from central Pennsylvania slaughtered the 14 remaining Conestoga people, completing a genocidal campaign against a people who had lived, unarmed, on a tract of land set aside by William Penn with the founding of Pennsylvania. Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga, a graphic novel and public art exhibition at the Library Company of Philadelphia that debuted this month, reinterprets this campaign, and its aftermath, from the perspective of the indigenous peoples at the center of this story.

We worked with The Inquirer to highlight the story of the Conestoga people and their enduring legacy. This is especially important during Native American Heritage Month and the Thanksgiving holiday — a day that often pays lip service to Native history — because the act triggered a series of remarkable events in Philadelphia.

The so-called “Paxton boys” marched on this city, where Moravian and Lenape peoples would be interned for more than a year. Quakers enlisted in a militia to defend the city from these marchers. And that most iconic Philadelphian, Benjamin Franklin, intervened to disband the mob and inaugurate one of colonial America’s first major print debates, the 1764 Paxton pamphlet war, when Paxton apologists and critics rushed to shape popular opinion by publishing pamphlets. While apologists falsely accused the Conestoga people of colluding with the Ohio Country Lenape and Shawnee warriors, opponents accused the Paxton vigilantes of savage behavior. By the time colonists went to the polls that fall, the exchange ballooned into a bigger political debate about governance, representation, and settlement policy.

As with so many American narratives, the voice of the Native people was drowned out in these colonial recriminations and has since been buried in the snows of time.

But on a warm October afternoon in 2017, a scholar working at the Library Company of Philadelphia traveled to New Mexico to meet “Head Indigenerd” at Indigenous Comic Con (then in its sophomore year) to discuss a graphic novelization of the 1763 massacres, reimagined from the perspective of Native peoples. By foregrounding the indigenous experience of those events, this project would provide a richer understanding of a historical event that reshaped Pennsylvania’s politics and cast a template for the Manifest Destiny of the 19th century.

The result of that conversation is Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga, a graphic novel and public art exhibition at the Library Company of Philadelphia.

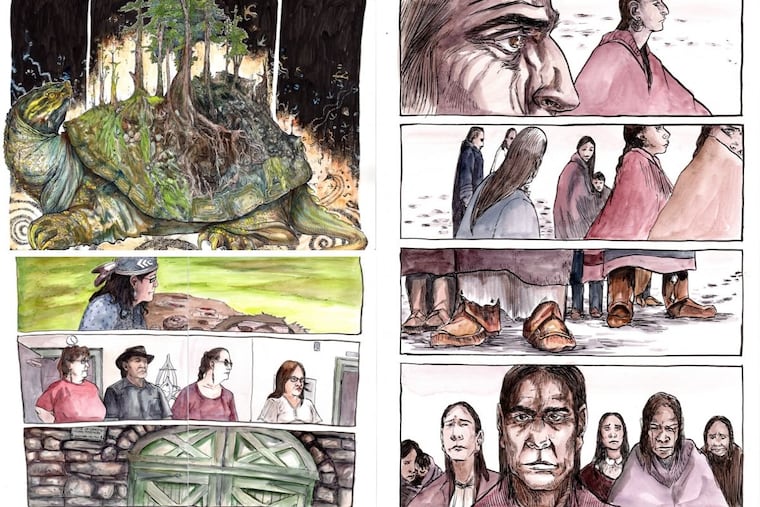

These three pages offer a glimpse at the art and values that animate this project.

The story begins at the true beginning — the Lenape origin story of Turtle Island. This narrative presents the land as the shell of a great turtle who raised its back from the waters to feel the warmth of the sun. In the image presented here, the opening spread of the graphic novel, artist Weshoyot Alvitre (Tongva) grounds our narrative in Native time and space. Working with Curtis Zuniga, a Lenape elder and adviser to the project, we opted to retell the story of Turtle Island to situate the Conestoga People in a wider intellectual and social tradition shared by Haudenosaunee Peoples and many others across the region.

At the same time, Alvitre particularized the origin story by integrating petroglyphs from rocks in the Susquehanna. Turtle Island serves as an invocation to the Conestoga people and a dedication to surviving kin, who sustain traditional practices, language, and memory through organizations like the Circle Legacy Center in Lancaster.

The second page could be titled Resistance. It shows the second attack on the Conestoga in the yard behind a Lancaster workhouse. When we set out to tell the story of the massacres of the Conestoga, we didn’t want to fetishize the tragedy. Instead, we wanted to highlight how the Conestoga people — and their kin interned in Philadelphia — embodied resilience. The Conestoga people didn’t die as victims. By the time they were removed to the site of the second attack, they would have known the dangers that awaited them. In Ghost River, the Conestoga people rise to face their aggressors.

The concept of Native peoples victimized and eventually erased by the wheels of westward conquest has long been a trope in popular media, including the engravings and political cartoons of the time. These records make conquest feel necessary or even inevitable.

By showing a people standing to meet their aggressors with resolve, we sought to create a new image rooted in resistance, agency, and self-determination. This image foreshadows the final pages of the book, which look ahead to the living kin of the present. Despite centuries of displacement and erasure, indigenous peoples have survived, thrived, and continued to tell their stories.

To treat the Paxton massacres as the genocide of Conestoga fails to account for the resiliency that this community had achieved through relocation, assimilation, and intermarriage. As local indigenous peoples at Circle Legacy Center repeated during our research trips to Lancaster, “We’re still here.”

We dedicate our final spread to those contemporary Native peoples, who we see meeting, remembering, and sustaining traditions. As the script of Ghost River evolved over the last eighteen months, we consulted regularly with Circle Legacy Center members who identify as Delaware, Lenape, Munsee, Onondaga, and Haliwa-Saponi. We’ve visited them at Mennonite Church in Lancaster. We’ve talked on the phone. We’ve broken bread together.

Ghost River is not a eulogy for some lost tribe; it’s an act of active and ongoing recollection sustained by and responsible to living, breathing people.

Visit the Library Company of Philadelphia before April 10 to explore the exhibition or purchase a copy of Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga.

Lee Francis (Pueblo of Laguna) is the author of Ghost River: The Fall and Rise of the Conestoga. Will Fenton is the editor of the volume and curator of the exhibition at the Library Company of Philadelphia.