What we learned from Philadelphia’s vaccine lottery

Whether developing a safe vaccine or figuring out how to encourage its adoption, the same scientific method — systematically experimenting to see what works and what doesn’t — is key.

Earlier this month, the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention authorized new COVID-19 booster vaccines with the hope of staving off another wave of hospitalization and death this winter. Invaluable as vaccines have been in the fight against COVID, only one in three American adults chose to receive the last round of lifesaving booster shots, which helps explain the nearly 500 daily deaths that are still being recorded in this country.

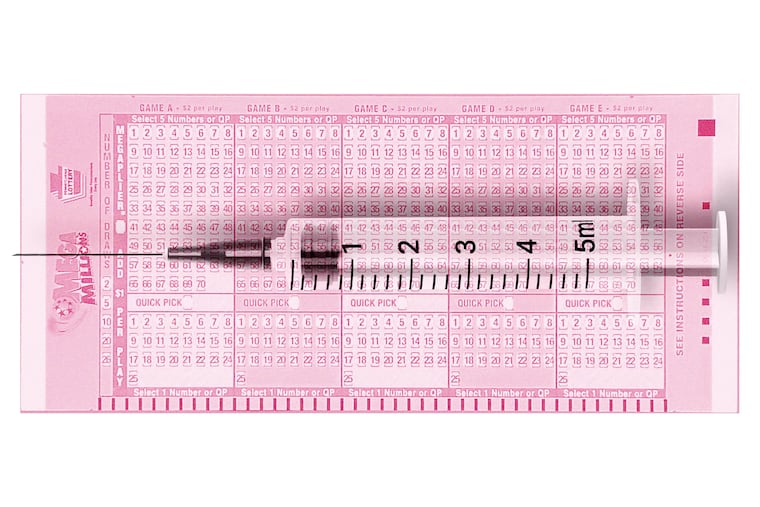

We recently published a paper in Nature Human Behavior summarizing what we learned from the Philly Vax Sweepstakes — a vaccine lottery with prizes worth up to $50,000 that was designed, implemented, funded, and evaluated by our research team at the University of Pennsylvania and carried out in partnership with the city of Philadelphia. In 2021, at least 21 states sponsored vaccine lotteries in which only vaccinated residents were eligible to win large prizes.

We developed the Philly Vax Sweepstakes to answer two policy questions: Could vaccine lotteries be effectively targeted at zip codes with especially low vaccination rates? And could a well-designed citywide lottery cost-effectively boost vaccinations in Philadelphia compared with surrounding communities?

Building on prior research, our sweepstakes was designed as a “regret lottery.” This means every adult in Philadelphia was automatically entered. However, prizes could only be collected by those able to prove they’d been vaccinated before their name was drawn.

Drawings took place three times over six weeks for a total of 36 prizes. Two weeks before each drawing, we randomly picked one of Philadelphia’s 20 zip codes with the lowest vaccination rates and announced that in that zip code, residents would receive half the prizes from the next drawing. Compared with other Philadelphians, residents of these zip codes had 50 to 100 times the chance of winning a cash prize.

So what did we learn? A surprising number of Philadelphians were paying attention and wanted to win.

Even though we announced that residents were automatically entered in the sweepstakes, one in 16 Philadelphians took the time to confirm their contact information was in our system over the course of the lottery. Philadelphians in the zip codes with inflated odds of a win were particularly eager to reconfirm their contact information. Despite this flurry of excitement, we’re confident that giving select zip codes higher odds of a sweepstakes win did not increase the adoption of vaccines in those zip codes.

» READ MORE: My school created a new curriculum integrating vaccine education. Others should follow our lead. | Opinion

It’s trickier to determine the impact of the overall regret lottery. Unlike the zip code boost, our team didn’t randomly choose cities to have (or not have) a regret lottery. We compared vaccination rates in Philadelphia with comparable Pennsylvania counties at the time of the sweepstakes to estimate its overall effect. The results of this comparison — while equivocal — are more promising.

Our best guess is that the overall Philadelphia regret lottery (which gave out a total of $378,000 in prizes) generated one extra vaccination for every $16 spent on prizes (or nearly 4,000 extra vaccinations of Philly residents per week of the six-week sweepstakes). In contrast, we’re confident that geo-targeting lottery incentives at selected zip codes failed to generate even one extra vaccination per $4,690 spent.

Caution is warranted, however. One relevant comparison city, Pittsburgh, saw a similar bump in vaccinations over the same period without a regret lottery. And a review of statewide incentive programs by some members of our scientific team found that direct rewards for vaccination and vaccine lotteries without a regret design had little benefit in the spring and summer of 2021.

Geo-targeting vaccine lotteries at the zip code level appears to be a waste of money, but citywide vaccine regret lotteries warrant further experimentation. Research has also shown that repeated text reminders from your pharmacy or doctor conveying that a vaccine has been set aside for you work well when vaccines are first rolled out. Since such reminders add little value late in the game, pharmacies and physicians should waste no time setting up those nearly cost-free nudges.

“Geo-targeting vaccine lotteries at the zip code level is a waste of money, but citywide vaccine regret lotteries warrant further experimentation.”

And of course, while controversial, requiring vaccination to access certain privileges — including restaurants, travel, and employment — has proven effective.

This will not be our last pandemic. The lesson of the past two and half years is that saving lives requires not only pharmaceutical innovation, but also behavior change. Whether developing a safe vaccine or figuring out how to encourage its adoption, the same scientific method — systematically experimenting to see what works and what doesn’t — is key. The Philly Vax Sweepstakes was important not because it was especially successful, but because it advanced our understanding of what doesn’t work to promote vaccine adoption (geo-targeting) and what might (regret lotteries).

Whether it’s to encourage boosters, monkeypox vaccinations, or immunization against another pathogen, citywide regret lotteries are worth another look.

Katy Milkman is the James G. Dinan Professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. @katy_milkman Angela Duckworth is the Rosa Lee and Egbert Chang Professor at the University of Pennsylvania. @angeladuckw Linnea Gandhi is a doctoral student and lecturer at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. @linneagandhi