At SEAMAAC, long-settled immigrants devote themselves to helping new arrivals | Philly Gives

The Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition began in 1984 by serving people from countries like Vietnam and Cambodia. It now assists anyone who is marginalized or low income.

To escape the soldiers, Mai Ngoc Nguyen swam across the Mekong River as Laotian snipers on the riverbank fired into the water. She and four others fled Laos together, but only Nguyen made it to safety in Thailand. The rest drowned before they could reach the opposite shore.

On her first night in Philadelphia, Kahina Guenfoud, an Algerian immigrant eight months pregnant with her first child, was exhausted. When it was time to sleep, she pulled what she could out of her single suitcase and tried to get comfortable on the floor of an empty house.

To this day, Thoai Nguyen remembers how he, his parents, and seven siblings were airlifted from South Vietnam to an aircraft carrier in the ocean. As the North Vietnamese moved into the area at the end of the Vietnam War, there would have been no mercy for his father, who had worked for the American government.

Every immigrant has a story and SEAMAAC can hold them all, serving the city’s low-income and immigrant community in more than 55 languages from its headquarters in South Philadelphia — just blocks from where Guenfoud spent her first night. Thoai Nguyen, the chief executive officer, still lives nearby in the South Philadelphia house where his family found refuge in 1975.

The majority of people who work for SEAMAAC (Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition) are immigrants in an organization that began in 1984 by serving people from countries like Vietnam and Cambodia and now assists all low-income and marginalized people, including immigrants from Asia, Africa, Europe, and South and Central America.

“It’s about the feelings,” Guenfoud, SEAMAAC’s adult literacy and access coordinator, said. “We feel what they feel. We have all left our families. We still have that emptiness inside.”

It’s why staffer Biak Cuai, SEAMAAC’s outreach worker to Philadelphia’s Burmese community, keeps her phone next to her bed at night. Everyone has Cuai’s number and they call when there is an emergency. “They call me and ask me to call 911: `My stomach hurts and I can’t breathe.’”

The hour doesn’t matter, she said, because she understands.

Many of the people who come to Philadelphia from what is now known as Myanmar are illiterate in their own language because education is no longer readily available back home, Cuai said. Here, even the basics, like opening a bank account, using email, or dealing with paperwork from their children’s schools, seem insurmountable.

“They come here because they feel America is the top country in the world, but the problem is that everything is new and unfamiliar,” she said. “They have fear. They are scared.

“I feel the same way because I am an immigrant,” she said.

“I prayed to my God to guide me to my dream job, so I can serve my people,” she said. “They knock on my door. I tell them, ‘if you have any problem, you can reach out at any time.’”

The stories are dramatic and the help is real.

In broad strokes, SEAMAAC provides education with classes in digital literacy and English as a second language (although for most immigrants, it’s English as a third, fourth, or fifth language).

“It’s about feeling and belonging,” Guenfoud said. “When you learn English you learn the culture, and if you learn the culture, you belong in this country. You’ll find your place here.”

There’s social work and legal assistance to help people obtain benefits or apply for citizenship. A separate stream of funding finances SEAMAAC’s support for children who are missing school due to difficult family situations.

SEAMAAC works with domestic violence survivors and has co-produced a short, animated film offering hope and support in 10 languages — Lao, Cantonese, Hakha Chin, Nepali, Bahasa Indonesia, and Khmer, among others.

Art therapy helps survivors cope with trauma. A domestic violence survivors group produced a collection of mosaics, each with a teacup, surrounded by shards of glass. What was broken, explained Christa Loffelman, health and social services director, can become something beautiful.

Many of the people who come to SEAMAAC have experienced trauma. “Everyone’s been through multiple layers of trauma,” she said. “You are displaced from your home country — not by choice — and you are going to a refugee camp in a different country. Their entire system has been disrupted.”

Traditional Western-style talk therapy doesn’t help. For one thing, the language isn’t there, and secondly, it’s not part of many cultures. What has worked, Loffelman said, is expressing feelings through art, and being together while doing it.

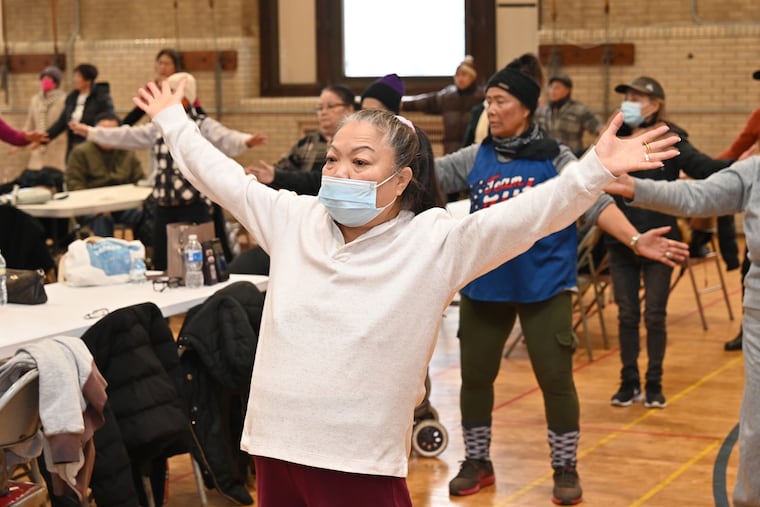

To counter the social isolation of seniors, SEAMAAC organizes meetings of “the Council of Elders.” They gather in a drafty gym at the Bok building, a former high school in South Philadelphia where SEAMAAC offers classes and counseling.

Often, the elders practice qigong, a form of movement meditation, or on a less esoteric level, enjoy multicultural bingo. Languages may be different, but when someone holds up a G-32 poster, everyone understands. If they don’t, Mai Ngoc Nguyen, a volunteer who can speak Laotian, Thai, Vietnamese, and English can help.

“Everyone’s been through multiple layers of trauma,” she said. “You are displaced from your home country — not by choice.”

She has experienced plenty of trauma and heard plenty of traumatic stories. She’ll never forget the mother who gave her baby medicine so it wouldn’t cry in a boat carrying refugees away from their country. The boat capsized. The baby drowned.

“She comes into the refugee camp and she became crazy, yelling `Where is my baby?’ Her brain got messed up” and she never recovered.

Luckily for Mai Ngoc Nguyen, then age 12, she was a strong swimmer and ready to cross the Mekong as she made her escape. But she had to kick away a friend who was clinging to her, dragging her under. Her friend never made it to the opposite shore.

“If you ask me, I’ll talk about it,” she said. “But if you don’t ask, I won’t talk.”

But she will joke, saying that she knows the Mekong alligators didn’t get her because they knew she needed to help her family back home.

It’s a lot of trauma, but every day at SEAMAAC isn’t full of anxiety. The elders coming out of the gym after bingo were smiling. And in a nearby classroom, students practicing their English last month traded jokes as they learned about Thanksgiving.

Fatma Amara, from Algeria, has been here long enough that she’ll serve a turkey on Thanksgiving, but the apple pie she makes will be Algerian, with seasoned apples layered among thin sheets of dough.

For her, SEAMAAC is more than a language class.

“At first, you feel lonely. You’re anxious. It’s stressful,” said Amara, who works in a hospital and is getting better and more confident with her English. “I take the classes, and we talk together and I feel better.

“Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday in America. It’s an international holiday. It’s about food and God and family,” she said. “You thank God for all you have.”

For all the blessings SEAMAAC provides, these days, funding is a struggle.

In 2024, SEAMAAC learned that the federal government had approved its application for a $400,000 multiyear federal grant to improve digital “equity.” But after President Donald Trump took office, federal staffers targeted “equity” programs. “That’s $400,000 we’ll never see,” said Thoai Nguyen, the executive director. “We would have had some of that money by now.”

Federal cuts since Trump took office have slashed SEAMAAC’s budget by 20%, he said. Hunger relief programs had to be curtailed, with 1,500 families who relied on SEAMAAC for food losing that lifeline.

“We’re in a moment,” he said, “where intentional cruelty is considered an acceptable form of political discourse.”

This article is part of a series about Philly Gives — a community fund to support nonprofits through end-of-year giving. To learn more about Philly Gives, including how to donate, visit phillygives.org.

About SEAMAAC

Mission: To support and serve immigrants and refugees and other politically, socially, and economically vulnerable communities as they seek to advance the condition of their lives in the United States. Services include ESL classes, job readiness, domestic violence survivor support, services for low-income elders, food assistance, public benefit counseling, health and nutrition education, and civic engagement.

People served: 8,000 families

Annual spend: $3,360,401 in fiscal year 2024

Point of pride: SEAMAAC plans to increase our impact to serve even more Philadelphians at its new South Philly East (SoPhiE) Community Center on Sixth Street and Snyder Avenue, scheduled to open in December 2026. In January, SEAMAAC, partnering with the American Swedish Historical Museum, will welcome visitors to “Indivisible: Stories of Strength,” an art exhibition showcasing the art and stories of South Philadelphians.

You can help: SEAMAAC provides many volunteer opportunities through our work in beautifying and improving Philadelphia’s neighborhoods through our work in urban gardening, tree planting, neighborhood and public park cleanings, and beautification of public schools and places of worship. Additional opportunities are available through our civic engagement and neighborhood unity events as well as by delivering groceries in our hunger relief efforts.

Support: phillygives.org

What your SEAMAAC donation can do

$40 provides shelf stable foods for a family impacted by the SNAP shutoffs for one week.

$50 provides holiday presents for two children.

$100 helps maintain one plot in SEAMAAC’s community garden for an entire growing season, providing tools, culturally appropriate seedlings, and soil.

$100 covers the full cost of supplies for one youth participant in SEAMAAC’s summer programs — giving young people the tools they need for career and college readiness.

$200 covers four hours of ESL instruction.

$250 provides 50 elders with a freshly made breakfast.

$250 provides a family with emergency food, hygiene items, diapers, and social service support for one month.

$300 supports a domestic violence survivor moving into safe housing, by covering the cost of utility hookups and household supplies.

$300 provides ingredients and cooking supplies for a nutrition education workshop.

$1,000 covers the full cost for one high school student to participate in SEAMAAC’s eight-week summer career exploration program.