As reparations debate continues, the University of Pennsylvania has a role to play | Opinion

It is disturbing when the bodily remains of enslaved people are warehoused at a school.

National conversation surrounding reparative action or reparations — payment to the descendants of enslaved people from institutions who profited off their labor — is gaining momentum. Congress held a hearing June 19 discussing a bill to authorize a commission on it, and some Democratic presidential candidates have stated their support, including Marianne Williamson, who has spotlighted this issue.

Meanwhile, here in Philadelphia, debate over the University of Pennsylvania’s complicity in slavery brews. The university denied any connection to the transatlantic slave trade in 2006, when university archivist Mark Lloyd said that Penn’s 18th-century trustees were not known to have profited from this abhorrent institution. These comments appeared in the Daily Pennsylvanian, prompted by the reckoning of Brown University and other institutions struggling with their complicity in slavery. A decade after that initial denial, Penn stated to the Philadelphia Tribune that the school had no direct connection to slavery.

Yet that conclusion has been challenged by the Penn & Slavery Project, founded in 2017 by students conducting archival research. The group has identified concrete connections between Penn and slavery, and found that Penn researchers were instrumental in developing racialized medicine, dimming the polished veneer of Penn’s Ivy. Their powerful work examined the legacies of former trustees, professors, and provosts, uncovering yet more buried histories of enslaved people whose stolen labor built these Ivy League institutions directly or indirectly.

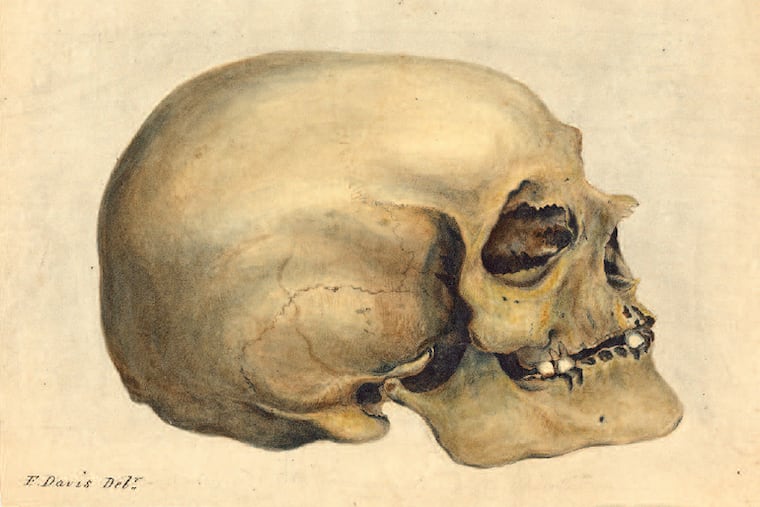

One focal point of the project is Dr. Samuel Morton, a 19th-century Penn graduate. Morton was a physician and white supremacist. His research supported the notion, known as polygenism, that different races were essentially different species. Morton wrote Crania Americana, which argued that a racial hierarchy could be derived from differences in cranial size. Morton writes that blacks are “joyous, flexible, and indolent” and that “nations which compose this race present a singular diversity of intellectual character of which the far extreme is the lowest grade of humanity.”

These conclusions support racist policy by highlighting false evidence that black people are born inherently inferior. This line of thinking professionally benefited Morton and colleagues. In 1846, fellow race scientist Josiah Nott wrote to Morton that his beliefs, which he referred to as his “n — ology, so far from harming me at home, has made me a greater man than I ever expected to be — I am the big gun of the profession here.”

Currently, Morton’s collection includes the crania of 53 individuals believed to be enslaved within their lifetime, 51 of whom are from Cuba, coming from a Vedado plantation before being shipped to Morton. Researchers believe that these individuals survived the Middle Passage. The remaining two are from a black woman from North Carolina and a black man from Delaware. All are housed at the university, according to research from the Penn & Slavery Project, drawing from catalogs of the Morton Collection and the work of scholars at the museum.

In response to the Penn & Slavery Project’s work, the university reversed its stance asserting it had no historical ties to slavery and announced it would form a working group to explore the issue further. Still, it is disturbing that bodily remains of enslaved people are warehoused at a school, to highlight the discredited science of a former professor in the name of historical preservation. I was appalled when learning about this during both a symposium on the Penn & Slavery Project and the spring final presentations of student researchers in April. I launched a change.org petition demanding the university return the remains to descendants — if possible — or inter them immediately.

Educational institutions during the formation of the U.S. increased their capital via wealthy slaveholders and their offspring — building a legacy from racialized capitalism, in which chattel slavery generated profit. These institutions upheld racial pseudoscience as academic rigor, spreading it with their academic prestige. The result was complicity in enslaving, dehumanizing, and killing black people, using our suffering as the basis for cultural and scientific output. The same medical falsehoods used currently to legitimize incorrect medical assumptions — including that black people can endure more pain than white people — find their seeds in the dirt of work like Morton’s.

Black people deserve reparations from institutions that benefited from the violence of the enslavement we experienced for generations. Penn is among the guilty. It also arguably continues to harm local black communities in West Philadelphia by driving residential displacement through university expansion. At the very least Penn can disavow Morton, and bury our ancestors.

Abdul-Aliy A. Muhammad was born and raised in West Philadelphia.