Coronavirus might never hit Philadelphia, but city needs to prepare for the worst | Editorial

Regardless of who leads the federal response, a coronavirus pandemic would place massive burdens on cities like Philadelphia.

President Donald Trump’s announcement last week that Vice President Mike Pence will head the federal response to the coronavirus is worrisome given his public health track record. As Indiana’s governor, Pence delayed decisive action during an unprecedented HIV outbreak among people who inject drugs.

Regardless of who leads the federal efforts, the most critical responders if and when the virus spreads among Americans will be local governments. We can take some comfort that between the seasonal flu, H1N1, SARS, and occasional mumps/measles outbreaks, our local health officials have training in this kind of virus transmission.

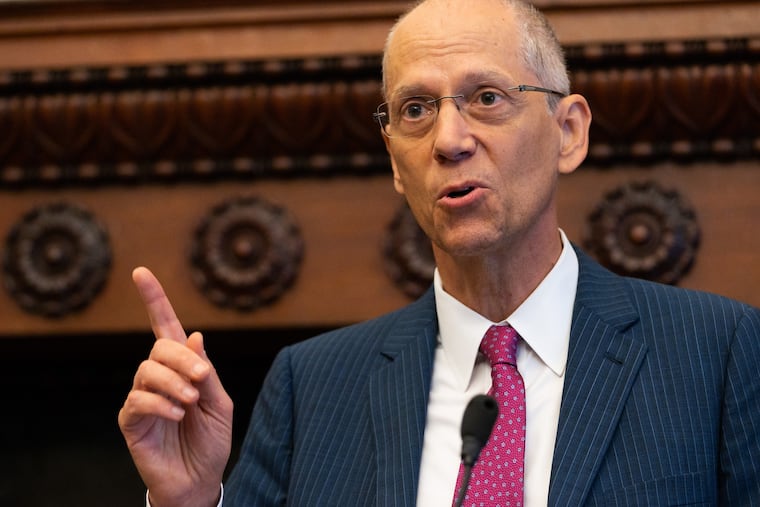

It is very hard to predict what coronavirus could mean for the U.S. — mostly because of the level of unknowns and how quickly the situation can change. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says there is no longer a question of if there will be community transmission of coronavirus in the U.S., but when — an assessment shared by Thomas Farley, Philadelphia’s health commissioner.

There is no reason to panic, but there is reason for urgency on the city’s part.

It will be Farley’s Department of Public Health that will be at the center of the storm, directing decisions about how the city responds. The response will have to involve every department in city government and many private sector entities, considering the staggeringly complex issues that a full outbreak could raise.

The main way to prevent and mitigate the spread of a virus like coronavirus — for which there is no vaccine or medication yet — is through nonpharmaceutical interventions such as social distancing — measures to reduce the opportunity for groups of people to gather. That can include closing schools — as Japan just did, potentially for a month — canceling events, and changing workplace patterns. That’s in addition to isolating people who might have been exposed.

Those scenarios raise a host of questions. For example, if schools close, the School District needs a learning plan to continue kids’ education. Parents who have to stay home to watch their kids could face a devastating financial blow, especially for low-wage or hourly workers. The city’s sick leave ordinance covers some Philadelphia full-time workers, but many others don’t get sick leave and often don’t have health insurance. In addition, many Philadelphia schools’ students depend on getting breakfast and lunch in school. How will children’s nutrition be impacted if children must stay home from school?

The city also houses a lot of people. If a homeless shelter sees a case of the virus and 40 people need to be in isolation, where would they go? How would the city’s jails deal with a potential infection?

These questions acknowledge just how complex the response to coronavirus might get, and how much falls on the shoulders of the city. The city needs to have answers to these questions — and the ones no one yet anticipates.

The Department of Public Health is about to launch a public website, a good step toward clear communication — which will also be critical. (https://www.phila.gov/covid-19)

This could be the calm before the storm, or the storm may pass us by. The city must be ready either way.