How to steal a house: Take advantage of holes in city’s and state’s security on property and death records | Editorial

Complaints about stolen homes have shot up from 44 in 2013 to 136 in 2018, according to the Philadelphia Department of Records. The city is changing its security system but declined to specify the upgrades fearing it would tip off scammers.

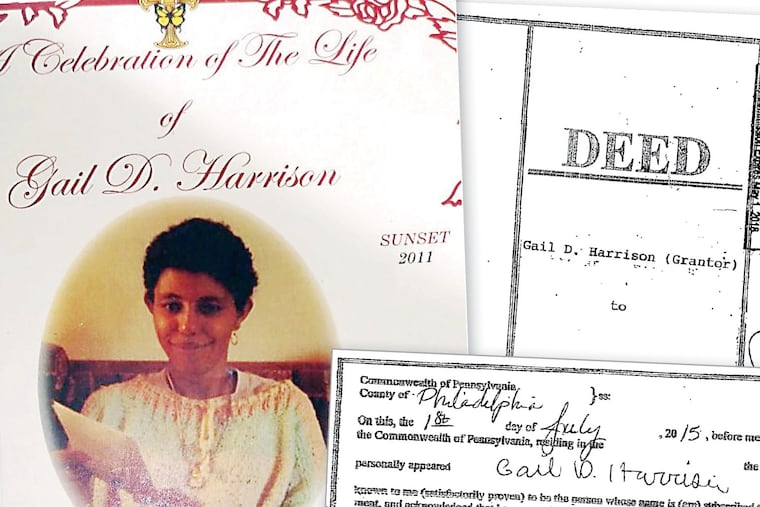

Gail Harrison kept to herself, rarely venturing from her two-story rowhouse on Seybert Street, in Brewerytown. She died at age 59 in 2011. A few years after her death, her home became the object of a growing Philadelphia scam — house theft.

One man allegedly forged the deed to her house and sold it at a huge profit. A second man allegedly filed a phony will to take the house, reported Inquirer staff writer Craig R. McCoy.

Prosecutors say that in 2016, William E. Johnson allegedly forged Harrison’s signature and that of a notary on the deed to Harrison’s home. He sold it for $89,000 to a developer, who flipped it for $250,000. The District Attorney arrested Johnson earlier this month on charges of stealing Harrison’s home and a half dozen others.

In 2017, the Register of Wills accepted Donnie McLaurin as Harrison’s rightful heir even though both her signature and that of a notary appear fake. (He didn’t get the house because Johnson beat him to it.)

The alleged scammers slipped through a bureaucracy that depends on people telling the truth, a quaint notion that when determining the disposition of someone’s property, is not a good idea. Not only was Harrison’s signature forged on the deed and the will but it is significant that the notaries’ signatures appear forged as well. The notary is the one person whom the government believes can authenticate an individual’s signature. But government workers, who process deeds and wills, don’t authenticate the notaries. They should — especially because house theft scams are a growing problem in gentrifying neighborhoods.

Complaints about stolen homes have shot up from 44 in 2013 to 136 in 2018, according to the city Department of Records. The department is making changes to its security system in the aftermath of the Inquirer stories, but it declined to detail the upgrades fearing it would tip off scammers.

City officials, in charge of deeds and wills, say they check to see if documents are properly notarized and require a photo ID from anyone filing them. But they don’t have the staff to fully authenticate a notary’s status. That’s inexcusable, especially since the Department of State has a simple search page to verify whether notaries are still active. The state has records showing notaries’ signatures, which should be digitized so government workers involved in property transfers can immediately see if notaries’ signatures on official state documents match those on wills and deeds; if they don’t, that should raise a red flag.

Another weak link is the Department of Health, which issues death certificates. In the case of the allegedly forged will, McLaurin presented a death certificate to the Register of Wills. Death certificates are available only to heirs but the state acknowledged it mails death certificates to people who say they’re relatives of the deceased. That’s just naive. The state should verify heirs.

In this digital age, it is not too much to expect city and state departments to take further steps to verify a document’s authenticity, especially given the growth in scams of all types — especially those who take advantage of the dead.