This Father’s Day, let’s celebrate Black dads

There are so many responsible, community-oriented men who are dedicated to their families. Take, for instance, my dad.

“I don’t know any deadbeat dads.”

My friend said this casually last weekend at a pre-Father’s Day brunch at her home in East Oak Lane. As she put last-minute touches on the food, she kept talking about the Black fathers in her life. “I don’t know any dads who don’t take care of their families, who don’t get up and go to work and try to make their communities better. And I just wanted an opportunity to celebrate a few of them.”

In other words, despite pervasive negative media portrayals of African American men as absentee fathers, that’s not what she sees.

Before we started piling food on our plates, she introduced each of the dads she had invited to the brunch: A former neighbor and Mr. Fix-it, who is always willing to tackle home projects. A track coach still in his Sunday necktie and white shirt from services at Salem Baptist Church in Abington. An assistant pastor. Her husband, who was on fish fry duty that day, works in insurance sales. My own husband was standing nearby, a retired project manager.

All of these responsible, community-oriented men, dedicated to their families, undermine this persistent stereotype of Black men as deadbeat dads.

Growing up, I never knew there was a negative stereotype about Black dads. That’s because of my father.

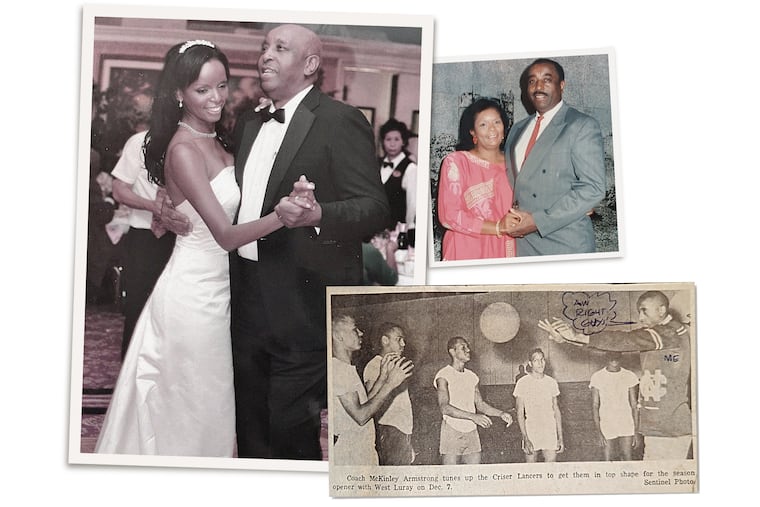

My dad stood 6 feet, 6 inches tall, and had a loud, booming voice, which must have come in handy during his career as a physical education teacher and basketball and football coach. He mentored countless youngsters throughout his decades-long career in Washington, D.C., and elsewhere, and under his leadership, the public high schools where he worked often dominated local basketball.

My dad loved people, and it seemed as if everyone loved him back. As a kid, I would marvel at how he couldn’t even walk outside our house in D.C. or go grocery shopping without hearing one of his former students call out, “Coach Armstrong!” Some of his former players went to college on athletic scholarships and even ended up playing professionally. Hundreds showed up at his funeral in 2010 to talk about the influence he had on their lives.

But to his five children, he was just Dad — the maker of pancakes topped with King syrup, the fixer of broken jacket zippers, the driver on family road trips, and the person who demanded we use the backboard when we did our jump shots. He used leftover wood from discarded school bleachers to build our backyard seesaw and picnic table. Our yard — with its regulation-height basketball goal and other amenities — was a neighborhood hangout.

He was hands-on before it was fashionable, doing everything that a good father should, which included being a loving husband to our mother, to whom he was married for more than 50 years. The late McKinley J.H. Armstrong set the gold standard for me — as well as for many others — as to what a good father should be.

Before moving to D.C., he taught in racially segregated schools in the South. I remember going with him to a reunion of some of his former students in North Carolina, who treated him like a returning hero. They talked about how he wrote their school song and taught them to sing it, showed them how to balance a checkbook, coached their award-winning athletic teams, and shared important life lessons.

Looking back, I don’t know how he and my mother put their five children through 12 years of parochial school and then college. For extra money, he waited tables for special events at a Marriott hotel, drove a taxicab, worked construction, and supervised summer camp at a nearby university. But with no fanfare. He just did it.

I knew even as a kid that I was blessed to have such a great dad. But here’s the thing: There are lots of men who are doing the same thing, quietly supporting their families, raising their children, paying bills, and caring for elderly parents. They defy every stereotype about uninvolved Black dads. But we don’t hear about them.

Since roughly 70% of Black babies are born out of wedlock, too many people assume the stereotype of the absentee Black father.

But just because the parents aren’t married doesn’t necessarily follow that the man is an absentee father.

Just look at the data. According to a 2013 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, African American fathers often are more hands-on with their children — bathing, changing diapers — than men from other racial groups. And most of the heads of single-father households are Black.

The data “really contradicts the statement that we’re not there,” Bilal Qayyum, founder of the Father’s Day Rally Committee, which hosted the 26th Annual Fatherhood Awards Reception on Wednesday at the Art Museum, told me recently.

I don’t deny the existence of men who aren’t doing enough for their families, who really need to step up and take care of their children. There are plenty of them out there. But despite what people might say, there are many Black men who don’t fit that stereotype. They love on their children and do what’s right. Even though the world would have you think otherwise.