Sadie T.M. Alexander, caught in the crossfire of a war to control America’s past

Penn Carey Law School's pause of a scholarship honoring a pioneering Black woman highlights a campaign to erase America's history.

Christopher R. Rogers knows how hard it is to stop the past from collapsing — especially when it comes to the rich tapestry of African American history. For nearly four years, the Haverford College visiting assistant professor of writing has been deeply involved with the floorboard-by-floorboard campaign to save a once-dilapidated home in Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion neighborhood that launched a Black cultural and political empire in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

Rogers is co-coordinator of Friends of the Tanner House, which is successfully working to save the small home on Diamond Street near Fairmount Park where the groundbreaking Black artist Henry Ossawa Tanner began painting his masterpieces from 1872 to 1888. But the Tanner House remained the center of Philadelphia’s Black intellectual life long after the painter decamped for Paris, largely because of racial prejudice in America.

It was also here that Tanner’s niece — Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander — lived while earning her economics doctorate at the University of Pennsylvania in 1921, on her path to becoming the first Black woman to earn a law degree at the Ivy League school in 1927. And after that, a pioneering lawyer fighting for civil rights in the mid-20th century.

Now, some 36 years after her death, Alexander has unexpectedly become one flashpoint in a fast-spreading battle over who gets to tell America’s story, and how. It was just last month that city officials announced a plan for a bronze statue of Alexander to be placed on the apron of the Municipal Services Building, not far from where the statue of the racially divisive 1970s’ Mayor Frank Rizzo was removed. The Rizzo removal and a city push for new statues of Alexander and other Black pioneers reflects the momentum for a more inclusive — and more accurate — version of history that was prompted by the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement.

But last week, Alexander’s legacy felt the stiff headwinds of racial backlash. As the University of Pennsylvania comes under intense pressure from the Donald Trump regime to drop diversity programs, Penn Carey Law School stunned Philadelphia’s civil rights community with word that it’s pausing the Dr. Sadie T.M. Alexander Scholarship, a free-tuition program that was also announced in the wake of the 2020 protests.

The law school is also closing its equal opportunity office, just days after the university announced a deal with the Trump White House to restore research funding and bar transgender athletes in women’s sports.

This week, Rogers — who earned his doctorate from Penn’s School of Education — said he was deeply disappointed in the latest move from a university that he accused of an Orwellian “doublespeak” from administrators, who hail racial diversity despite a track record of rocky relations with its predominantly Black neighbors in West Philadelphia.

“We know that [Alexander’s] legacy stands for civil rights,” Rogers said. “It stands for justice, it stands for equity, it stands for democracy, it stands for knowledge. And so, if they are invested in those things, it definitely is surprising to see them in some ways sell out …”

Penn Carey hasn’t offered any detailed explanation of why it announced the pause, which means no Alexander scholarships will be offered in the new academic year, although current scholarship holders will still be supported. The law school said in a statement to my Inquirer colleague Susan Snyder that “details about the program’s future will be shared as the Law School continues to assess next steps.”

But this didn’t happen in a vacuum. The pause in a program honoring Penn’s first Black female law degree recipient is just one skirmish in a broader push by the Trump regime to write an entirely new draft of U.S. history that epitomizes his personalist, strongman rule by highlighting what the president calls “American greatness.”

The flip side of that relentlessly positive rewrite is to whitewash any blemishes on our national story — especially around slavery, Jim Crow segregation, and other race-related injustice. Shortly after taking office, Trump claimed in an executive order that Washington’s flagship federal historical museum, the Smithsonian Institution, had “come under the influence of a divisive, race-centered ideology.”

Now, the Trump administration has ordered a sweeping review of all the Smithsonian’s exhibits and permanent collections aimed at what the New York Times called “a more uplifting view of American history.” Historians fear the real purpose is sanitizing the truth about a nation that blazed a trail for democracy, even as it also dropped atomic bombs, rounded up Japanese Americans into camps, and drove Indigenous people from their land.

The battle for the heart and soul of the Smithsonian is part of a broader crusade that is also looking at removing references to slavery or other stains on the American Experiment from a range of federal historical sites, including many in Philadelphia, such as Independence Hall and the President’s House, where enslaved Black people worked for George Washington. Perhaps more significantly, Trump has pushed since his first presidency for a similar version of U.S. history to be taught in the classroom.

» READ MORE: George Floyd’s 2020 murder promised a ‘racial reckoning.’ Instead, we got Trump | Will Bunch

It’s important not to dismiss the regime’s intense interest in the American story as a hobby. As anyone who has read George Orwell’s 1984 and internalized one of its most famous quotes — “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.” — knows, throwing hard facts down a memory hole and spinning historical fiction is central to the authoritarian project.

Indeed, it was the backlash whipped up among mostly white voters after those 2020 protests over the police murder of George Floyd — the ones who took down Rizzo’s statue and raised up the Alexander scholarships at Penn — that Trump rode to his unlikely second term in the 2024 election.

A key “thought leader” for Trump’s MAGA movement, Christopher Rufo, manufactured the idea that what he called indoctrination about the American story was behind the marches for racial justice that terrified a swath of white America.

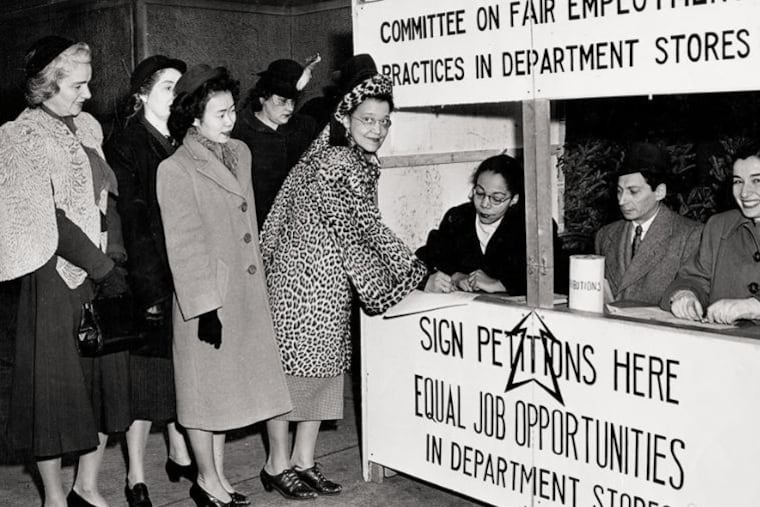

That movement for a racial reckoning was, in many ways, epitomized by the drive to resurrect the nearly forgotten story of Alexander and the grit she displayed in earning a law degree when there were few such opportunities in a heavily segregated society. Alexander herself once said that in law school at Penn, “I was met with many obstacles, but I was strong enough then not to let them worry me.”

This is said to have included a dean who treated her with discrimination and tried — unsuccessfully — to keep Alexander off the law review. The prejudice she encountered at Penn in the 1920s inspired her career as a lawyer who crusaded for civil rights, fighting segregation in Chester County schools, Philadelphia’s public facilities, and even the U.S. military. This tale of overcoming adversity is what inspires today’s activists like Rogers to fight not only to save the Tanner House from the wrecking ball, but hopefully to again make it a center for Black thought and community activism.

“It’s not just the story of bricks and mortar,” he said. “It is a story of our African American history, of the obstacles that we have faced and how we have relied on community, relied on a sense of values of equity and justice to be able to sort of transcend those conditions in the small ways that we do, to serve as models of possibility for the type of world that we want to see come into being.”

Rogers said Trump’s campaign of historical erasure and Penn’s seeming capitulation make Alexander’s story more important than ever, because this is “where we have to come together and fight for it. You know, they’re not going to be given, right? These are the things that we have to come together and fight for.”

The war for American history matters not only because facts matter, but also — more concretely — Trump and his MAGA minions know that a fake version of where our country has been will make it easier to sell a twisted vision of where they think it needs to go, including the inhumane mass deportation of immigrants, a militarized and brutal brand of law and order in U.S. cities, and a government that looks just like the tyrannical monarchy we overthrew starting exactly 250 years ago.

In that world, the real story of American greatness — Black and brown people, Native Americans, the LGBTQ community, and so many others on the margins fighting for 249 years to make an imperfect democracy work for everyone — becomes an inconvenient truth. It’s a world where the essential story of Sadie T.M. Alexander can be “paused.” And as the big institutions like Penn cower, we the people must fight to keep it alive.

» READ MORE: SIGN UP: The Will Bunch Newsletter