Renaming Camden’s Woodrow Wilson school could be more than a history lesson | Kevin Riordan

There's talk about changing the name of Woodrow Wilson High School in East Camden.

A fledgling effort to remove Woodrow Wilson’s name from a public high school in Camden has taught me a few things about the former U.S. president, journalism history, and myself.

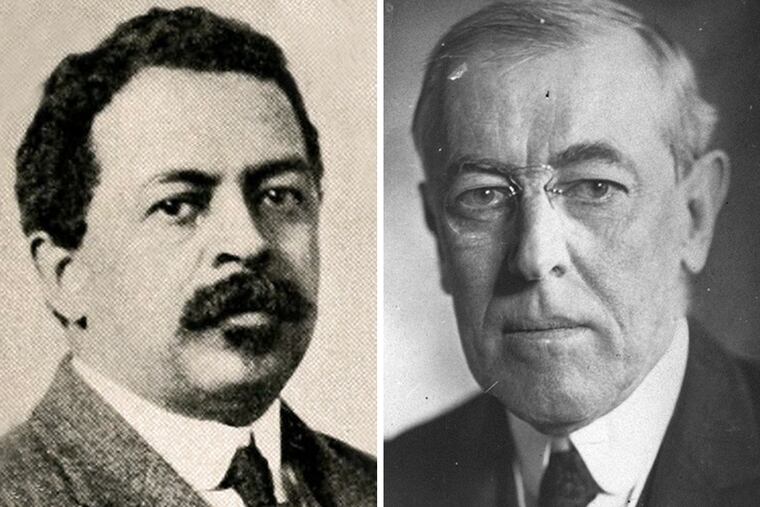

In an op-ed published last week in the Camden Courier-Post, educator Rann Miller of Gloucester Township argued that Wilson’s virulent racism is not an irrelevant artifact most suitably viewed in the context of the early 20th century, but an ugly and enduring fact of American life that “cannot be ignored or excused for the sake of celebrating [Wilson’s] accomplishments.”

The op-ed followed the recent launch of a Change.org petition about changing the name; 40 people had signed as of Tuesday.

Miller’s op-ed noted that Wilson “oversaw the re-segregation of government employees while firing black government supervisors like James Napier, whose signature appeared on every dollar printed in 1912 [as] register of the Treasury." And during Wilson’s presidency, "the federal civil service instituted a policy of requiring photographs on all job applications, to ensure that more black workers would not be hired,” wrote Miller.

As if Wilson’s agreeing to a White House screening of The Birth of a Nation — the film depicting the Ku Klux Klan as superheroes and black people as subhumans — wasn’t bad enough.

I liked Miller’s op-ed and wanted to share it on my Facebook page. But I’ve long had qualms about what can seem a rather faddish attempt to rename buildings and remove statues as a tool for social justice. However deeply felt and well-intended, such actions too often strike me as Orwellian and far too easy — feel-good moves to prettify the present by papering over the past. Like acts of retroactive revenge that in themselves don’t come close to undoing injustices.

So when posting a link to the op-ed, I also posed a question.

How would changing the name help the school? Or the students?

Friends and followers responded fast.

[Changing the name] would help by showing the children that people with views such as his do not deserve reverence, they deserve to be buried in history.

[Having that] sign on the building tells children of color yet again that the government that holds power over their lives ... feels this is someone worth honoring.

It takes a certain level of privilege to tell black and brown communities how they should feel about racist symbols of the past. And quite frankly, it’s insulting, and we’re tired of it.

Seems my high-minded concerns about erasing history, and my fretting about what I dismissively characterized as a merely “symbolic” name change, left me little room to imagine how Wilson High graduates of color might feel about forever carrying the name of an egregiously racist president on their diplomas.

As a white man, I’ve never had to contemplate, much less put up with, having a life achievement officially cheapened in such a cavalier, if not cruel, manner. To have this done by an educational institution that seems ignorant of the appalling beliefs of its namesake is even worse.

Online comments about Miller’s op-ed, most posted by white folks who seemed eager to belittle the name change as a ludicrous exercise in political correctness, offered me yet another chance to check my privilege.

But it was my colleague Jenice Armstrong who, as she often does in her columns, connected the issue’s heart with my own. In a Facebook comment, Armstrong wrote that Wilson “threw a prominent black journalist out of the White House because the newsman dared to confront him about segregation.”

I’ll admit I’d never before heard of this pioneering journalist, whose name was William Monroe Trotter. But I expect I’ll remember his name going forward.

And while I recognize the Wilson High decision is Camden’s to make, why not rename it after William Monroe Trotter?