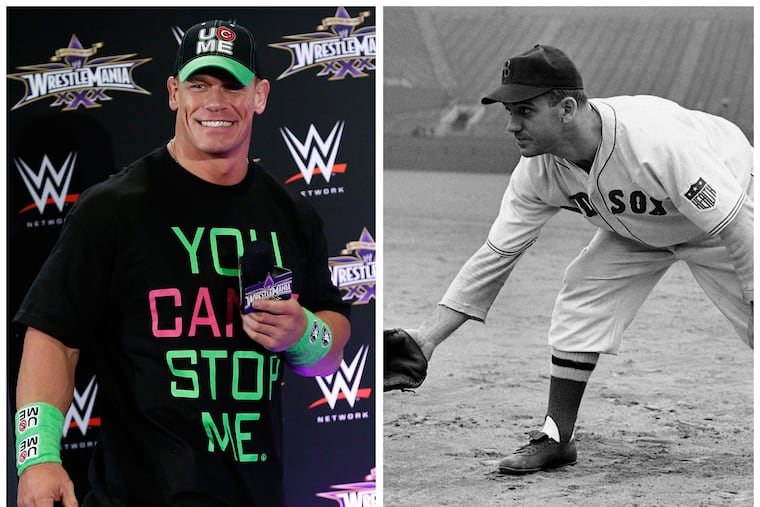

John Cena’s grandfather played for the Phillies and protested when they traded him away

Decades before his grandson became a movie star, Tony Lupien was traded to the Hollywood Stars. But he just wanted to play first base for the Phillies.

Tony Lupien drove to Philadelphia in February of 1946, just a few weeks before the Phillies were scheduled to begin spring training. Lupien missed most of the previous season after being drafted into the Navy during World War II and still didn’t have a contract for the new season.

There was a good reason: Phillies general manager Herb Pennock told Lupien he was being traded to the Hollywood Stars, a minor-league team.

Lupien was livid. He believed his job in the majors was guaranteed to him for a year after returning from the service and hired a lawyer to challenge the team’s decision.

“Who the hell are you to think that you’re above the federal government?” Lupien told Pennock.

» READ MORE: Paul Staico, owner of South Philly bar dedicated to Kansas City Chiefs, dies at 59

Lupien’s grandson would become one of the biggest stars in professional wrestling before embarking on a Hollywood career. But John Cena’s grandfather didn’t want to be a Hollywood Star. He wanted to play first base for the Phillies.

“Lupien, guaranteed a year’s job with Phils under selective service law, gets kick in pants instead,” wrote a headline in The Boston Globe.

Ulysses “Tony” Lupien graduated from Harvard and joined the Phillies in 1944 after being waived by the Red Sox. He hit .283 in 1944 before being sworn into the Navy in March of 1945. Lupien spent six months on a Naval base in New York before returning to the Phillies in September, just in time for the final stretch of a 108-loss season.

The Phillies were so bad in 1945 that their manager quit in June. Lupien, a smooth fielder, was a bright spot when he returned at the end of the season, hitting .315 over 15 games.

The Phils ranked last that season in nearly every statistical category, even attendance. The Phils wanted to clean house, declaring that any player who was in the lineup for the final game of 1945 would not be in the lineup for the first game of 1946. So that meant Lupien was gone.

“The G.I. Bill was designed to protect for at least one year the jobs of men who entered the service. Now that bill either applies to ballplayers or it doesn’t,” Lupien told The Sporting News. “That’s what I am trying to find out, and if it means that I am the goat or the ball carrier, I am perfectly willing to assume that role. If the G.I. Bill does apply, then I may help many other veterans in the months to come by following through with my action.”

The Phillies disagreed with Lupien as Pennock said the G.I. Bill didn’t apply to baseball. They had signed Frank McCormick, a 35-year-old power hitter, to play first base and the 29-year-old Lupien had a minor-league gig waiting in California.

» READ MORE: Rollouts have ‘twisted the knife’ at Big 5 games for 70 years, but can the tradition endure?

“I think the least the Phils might have done is give me a chance to show what I have,” Lupien said.

Lupien wrote a letter to the National League commissioner. He hoped to become a free agent or at least get invited to spring training. Lupien already played three years in the minors and didn’t want to go back.

His letter was returned unopened. Lupien’s lawyer, a former Harvard classmate, said he had a case. The Massachusetts Selective Service Board said the case would have to be heard in Philadelphia since it involved the Phillies.

The Hollywood Stars sent him a contract for $8,000, which made him the highest-paid player in the minor leagues. He learned the Phillies were kicking in $3,000. The Phillies, Lupien believed, were circumventing the G.I. Bill by making sure he still earned his prewar salary despite not giving him his old job.

Lupien already had two children and knew it would be too expensive to travel back and forth to Philadelphia to fight his case. He reported to Hollywood at the end of spring training and became a Star.

Lupien played two seasons with the Stars before returning to the majors in 1948 with the White Sox. He then bounced around the minors as a player/manager and coached basketball at Middlebury College before being hired in 1956 to coach Dartmouth College. He managed the team to the College World Series in 1970 and co-wrote a book in 1980 about the history of baseball’s labor movement. Lupien remained outspoken about labor, believing the sport’s contract structure railroaded his career.

He died in 2004, two years after Cena debuted in the WWE. Cena, whose mother, Carol, is Lupien’s daughter, said next Saturday night will be the final match of his career.

» READ MORE: Bucko Kilroy was once called the NFL’s dirtiest player. He became much more than that in a six-decade career.

Cena, 48, once wore a Phillies jersey to the ring and is one of the most popular performers in wrestling history. His celebrity has long crossed over into popular culture as he’s starred in movies and TV shows.

He spent the last year balancing his WWE farewell with the filming of a new movie. After wrestling, Cena is expected to fully become a Hollywood star. His grandfather, begrudgingly, was one first.