Remembering the local team that played in the first Negro Leagues World Series 100 years ago

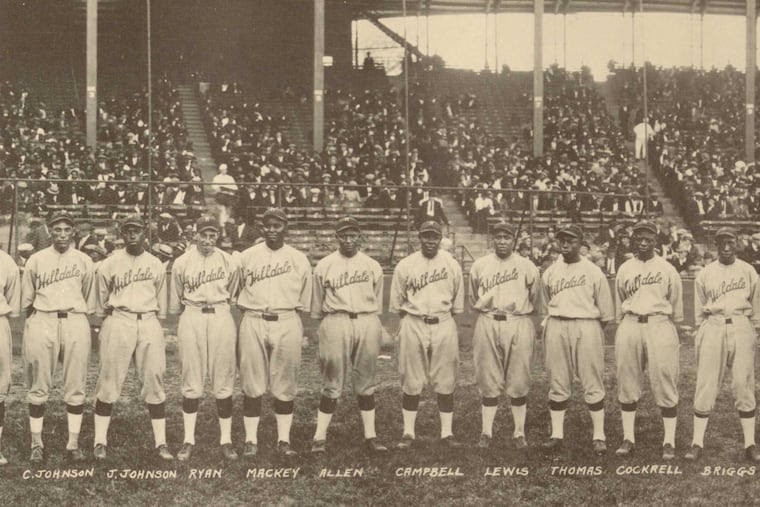

Darby's Hilldale Athletic Club played in the 1924 Negro Leagues World Series against the Kansas City Monarchs. Several of its players went on to the baseball Hall of Fame.

On MacDade Boulevard in Yeadon, there’s a dark blue sign standing in front of a parking lot. Nearby there is a beauty supply store and a seafood restaurant, and across the road is a cemetery.

It’s not an area that really makes you think “baseball,” but once upon a time, that was exactly the reason people flocked there — not for seafood or cosmetics. Before it was paved over and urban sprawl crept in, this was where Hilldale Park once stood, home to one of the best Negro League baseball teams in the country.

“The Hilldale Athletic Club (The Darby Daisies),” the sign reads in yellow lettering. “... Darby fielded Negro League teams from 1910 to 1932. Notable players included baseball hall of fame members Pop Lloyd, Judy Johnson, Martin Dihigo, Joe Williams, Oscar Charleston, Ben Taylor, Biz Mackey, and Louis Santop. Owner Ed Bolden helped form the Eastern Colored League.”

The blue historical marker was erected in 2006 to celebrate the team from Darby and its legacy.

2024 marks 100 years since the first Negro Leagues World Series, contested between the Hilldale Club of the Eastern Colored League and the Kansas City Monarchs of the National Negro League. The first two games were played in Philadelphia.

“They deserve to be remembered,” said Neil Lanctot, baseball historian and the author of Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932. “They’re probably the most significant African American team in Philadelphia.”

While Kansas City won the best-of-nine series, 5-4, Hilldale cemented itself as part of the bedrock of Black baseball history. And that would not be its last time on that stage.

The mark of Ed Bolden

Ed Bolden, of Concordville, was a Black postal worker.

He started volunteering as Hilldale’s scorekeeper on the side in its first season in 1910, when he was 28.

The Hilldale Club was purely amateur, made up of players ages 14 to 17, and managed by a 19-year-old named Austin Devere Thompson. At first, Hilldale was nothing special, one of countless amateur and semipro teams that had cropped up in this era.

But Bolden had a different vision for the team, which he would turn into a reality when he eventually took over as manager and later president. The entire time, Bolden maintained his regular job as a postal worker.

Bolden directed the construction of Hilldale’s diamond in 1914, which was a major key to the club’s transformation. While other semipro traveling teams had to contend with scheduling headaches that come with barnstorming, the Daisies had a home of their own. Their permanence had the additional benefit of attracting Black baseball fans from across the East Coast.

“I always think it doesn’t get enough credit, but Philadelphia was probably from a financial perspective, the best venue in Negro League baseball historically,” Lanctot said. “It always drew fans.”

The Hilldale corporation’s records are still available at the African American Museum of Philadelphia.

“They were an all African American-run team, which really was not that common,” Lanctot said. “That’s one part of the Hilldale story, how Black entrepreneurship was very significant in their development.”

Bolden helped form the Eastern Colored League in 1923, breaking off from Rube Foster’s Negro National League, of which Hilldale had been an associate member. In creating the new East Coast League, Hilldale and other charter members — the Bacharach Giants, the Brooklyn Royal Giants, the Cuban Stars, the Lincoln Giants, and the Baltimore Black Sox — poached many of the top NNL players.

Hilldale won the inaugural pennant in 1923, finishing the season 37-21-1. But the two leagues were in conflict during that season, a rift comparable to the one between the American League and the National League two decades earlier. Beyond the ECL championship, there was no greater prize for the Daisies to strive for.

But, again following the trajectory of the AL and NL, the two separate leagues settled their differences in 1924 and agreed to respect each other’s contracts. This would set the stage for the first-ever World Series later that year.

“That was a giant step forward, because the leagues were in many ways trying to mimic Major League Baseball,” Lanctot said.

The contenders

The Kansas City Monarchs and their stars are synonymous with Black baseball history. But for a few years, a team from Darby was their greatest competition.

The Monarchs are recognized as the team with which Jackie Robinson got his professional start. But it was also one of the most successful baseball franchises of all time. In their 24 years of existence, the Monarchs had only one losing season. They racked up 10 pennants in 12 playoff berths, and produced the most MLB players of any Negro League team.

Fourteen members of the Baseball Hall of Fame played for the Monarchs at one point during their careers, including two star pitchers of the 1924 team: Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and José Méndez.

Rogan, like several players on both Kansas City and Hilldale, was a World War I veteran, and played on the 25th Infantry’s baseball team while he served. A spectacular two-way player, Rogan posted a .396 batting average in the 1924 season while maintaining a 1.74 earned run average.

Méndez was born in Cuba. Before joining Kansas City, he’d already gone toe-to-toe with major league players who barnstormed in his home country, and Méndez often won. On Jan. 12, 1914, The Inquirer profiled Méndez, calling him “Cuba’s Black Mathewson,” in reference to legendary pitcher and Factoryville, Pa., native Christy Mathewson.

“Méndez is a wonder,” said Hans Lobert, the Phillies’ third baseman from 1911-14.

On the other side, the team from Darby had changed a lot in 14 years. Hilldale had transformed from a group of local young amateur players to a professional organization with a roster that had the star power to rival the Monarchs.

“They were kids; they transformed into a professional club, which is a pretty remarkable undertaking when you think of it,” Lanctot said.

Julius “Judy” Johnson of Wilmington is considered one of the best third basemen to ever play in the Negro Leagues, while Biz Mackey is considered one of the best catchers. Louis “Big Bertha” Santop, the Daisies’ 35-year-old backup catcher, hit cleanup and carried an average of .407 into the series.

When Johnson was elected into Cooperstown in 1975, he became the first person from Delaware to earn the honor. Santop and Mackey, both from Texas, joined him in 2006.

Jesse “Nip” Winters, Hilldale’s ace, was the only left-handed pitcher on the Daisies’ pitching staff. In 1924, he had a 20-5 record and a 2.77 ERA. He would go on to have a professional career spanning 14 years; in 1926, Winters pitched in an exhibition game against a group of MLB all-stars, and won a pitcher’s duel against Lefty Grove.

The first World Series

Before the series, the mantle of the top team in Black baseball had never been officially determined. Many claimed the title, but only in 1924 could it be officially bestowed.

The Inquirer provided some coverage of Hilldale, especially as the team became more dominant. But from the beginning, the Daisies were covered extensively by Black newspapers like the Philadelphia Tribune and the Pittsburgh Courier. Part of that can be credited to Bolden, as he befriended Tribune reporters and asked them to cover his team’s games.

The Courier, one of the widest circulated Black newspapers in the country, dedicated several pages of newsprint to Hilldale in its weekly edition throughout the fall of 1924, and sent reporters to every game of the World Series.

“With thousands of visitors from all sections of the country invading the city, with the sport loving element pouring in from baseball centers by rail and by auto, the Pennsylvania metropolis is a seething mass of excitement as the day for the opening game looms,” the Courier wrote on Oct. 4, 1924.

The series was best-of-nine, but technically took 10 games to be decided, after Game 3 was called at 6-6 after 13 innings when it became too dark to play. Games 1 and 2 were held in Philadelphia at National League Park, also known as Baker Bowl, then the home of the Phillies.

The series started poorly for Darby in front of more than 5,000 local fans, with what the Courier called a “Tragedy of Errors.” Six Hilldale errors, including three by pitcher Phil Cockrell in the fifth inning alone, sank the Daisies, 6-2. With Rogan on the mound for the Monarchs, Hilldale didn’t score a run until it was down to its final out.

Game 2, however, was redemption for the Daisies. Winters scattered four singles in a shutout and Hilldale collected 15 hits in an 11-0 victory.

Following the Game 3 tie in Baltimore, Game 4 looked to be headed in a similar direction, with the score deadlocked at 3 in the bottom of the ninth. Hilldale capitalized on a pair of walks and two Monarchs errors to walk it off and take the edge in the series.

In Game 5, the series shifted to Muehlebach Field in Kansas City, and fans were treated to a duel between Winters and Rogan. While the Monarchs jumped on Winters early, scoring their only two runs in the first inning, the Daisies’ ace was stellar late in the game. An inside-the-park home run by Johnson in the top of the ninth scored three for Hilldale, and proved decisive in its 5-2 victory.

But the momentum shortly swung back in the Monarchs’ favor, as they won Games 6 and 7 in Kansas City, as well as Game 8 at Schorling Park in Chicago.

In Game 9, Winters kept Hilldale alive for his third win of the series to force Game 10.

But in the decisive game, Méndez added another chapter to his legend, starting his first game of the series after previously only appearing in relief, and throwing a shutout. For Hilldale, submariner Scrip Lee had been equally formidable on the mound through eight innings. But when Lee altered his delivery late in the game, Kansas City exploded for five runs in the eighth to win the inaugural Negro Leagues World Series.

1925 champions

The tale of the Monarchs-Daisies rivalry was not over. In 1925, Hilldale won its third ECL pennant in a row with a 45-13 record. The NNL, on the other hand, had decided to hold a league championship series to determine its representative in the World Series. The Monarchs beat the St. Louis Stars to set up a rematch with Hilldale.

And Hilldale got its revenge, downing the defending champions to win the second Negro Leagues World Series, 5-1.

While Rogan had been key in the Monarchs’ win over the Stars, he was injured ahead of the World Series and was unable to play, dealing a severe blow to Kansas City’s pitching staff.

Hilldale won Game 1 at Kansas City in extra innings. While the Monarchs evened the series in Game 2, the Daisies won the next four, including the final two games at Baker Bowl. Rube Currie was the winning pitcher in Game 5 in front of 9,000 fans, the largest crowd of the series.

Cockrell earned the series-clinching win in Game 6, which was played in freezing temperatures.

“Clan Darbie is the new champion of Negro baseball,” W. Rollo Wilson wrote for the Courier on Oct. 17, 1925. “...Their hands did not get as cold, their bodies did not get as chilled; their brains were not sluggish with the frigidity. They won handily on a day better suited for toasting popcorn before blazing logs in the baronial halls than indulging in the great American pastime in wide, open spaces.”

Forgotten history

Hilldale had reached the top but was not able to stay there for very long. The World Series never drew as much money or fans as the teams had hoped, and the league disbanded in 1928. As the Great Depression seized the country in the 1930s, the Daisies folded entirely.

One-hundred years on, the story of Hilldale is often overlooked because of the club’s lack of longevity.

“It’s always the Crawfords and the Grays and the Monarch teams that tend to get the most attention,” Lanctot said. “They’ve never really looked at some of the other clubs.”

Bolden, on the other hand, was a mainstay in Negro Leagues baseball for decades. After Hilldale folded, Bolden founded its successor, the Philadelphia Stars. But while he could be considered the Eastern counterpart to Foster, he has not received the same recognition.

Bolden was inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame only recently, in 2022. He was considered for Cooperstown in 2006 but ultimately left out.

“The Hall of Fame, I think he could have been considered as a builder,” Lanctot said. “Negro League baseball is getting a lot more ink these days and more respect. ... Just for the length of his career, a 40-year person who was instrumental in the formation of the first successful Eastern Colored League, I think he does deserve more attention.”