Are Puerto Rico’s ‘undemocratic’ reforms a model for U.S. states and cities?

"Public employees are such a powerful and well-connected interest group"

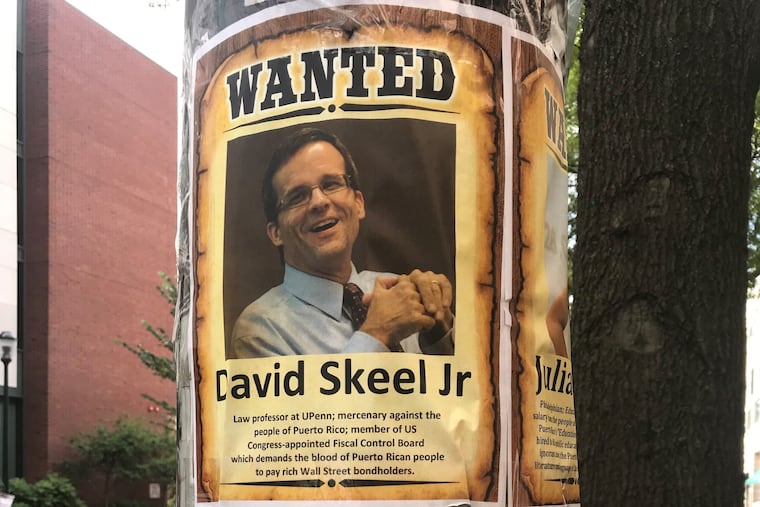

In West Philly last month, I saw a wanted poster of a guy I know. Smiling David Skeel, the anonymous author wrote, is "a mercenary against the people of Puerto Rico," as a member of the fiscal control board, headed by insurance broker José Carrion III, "which demands the blood of Puerto Rican people to pay rich Wall Street bondholders."

Skeel is a mild-mannered, high-energy Penn Law professor and author of Debt's Dominion, a history of bankruptcy. He writes learned essays for finance lawyers and public-policy thinkers. He told National Public Radio listeners how to make sense of the last financial crisis. He does not look like an iron-helmet conquistador, nor a whip-wielding capataz on a brutal hacienda, nor even a phlebotomist. How did he end up slagged in the over-the-top language that strongman-style politicians usually reserve for partisan enemies, or journalists?

Getting called names was practically in the job description for Skeel, Carrion and five others tapped by President Barack Obama in 2016 to three-year terms on the Puerto Rico Fiscal Oversight and Management Board. The board is part of the PROMESA plan, passed by both parties in Congress, charged with setting easier terms for paying back tens of billions of dollars that had been recklessly, or desperately, borrowed by governments and public authorities on America's Caribbean island colony over many years. It's also the board's job to find more money to pay with — from an island that's poorer than any U.S. state.

In a paper for the University of Puerto Rico's Revista Jurídica, Skeel puts PROMESA and the board in context as a next step on the hard road of American public bankruptcies, from the 1975 New York City fiscal board that paved the way for that city's renewed prosperity, through the 1990s Washington and Philadelphia oversight boards that forced those cities to raise taxes when they spend more, and the recent Detroit bankruptcy that shifted city assets to private foundations and got a judge and unions to trim unfunded pensions instead of cutting police.

Skeel thinks Puerto Rico could be the model for "substantial cities" such as Philadelphia, and maybe for wealthier but fiscally irresponsible states, that continue to rack up billions in unfunded retirement and health-care promises, refuse to boost taxes or cut programs, and may finally run out of cash to pay police or teachers. (Illinois, New Jersey and Pennsylvania lead the list of U.S. states with the lowest credit ratings, with fat pension deficits and spending imbalances.)

He acknowledges the "undemocratic" features of a board appointed by Congressional mandate. Isn't that an obvious sign of failure by local elected leaders? "Public employees are such a powerful and well-connected interest group" that elected officials won't dare cut programs, jobs, or benefits to make sure bills get paid, Skeel wrote.

The board is a threat to everyone who profited or was protected by the deep-debt regime. "Points of tension include the board vs. the Puerto Rico government; general-obligation bondholders vs. sales-tax bondholders; and government employees" against deep-in-debt agencies, wrote Alan Schankel, managing director at Janney Montgomery Scott Inc. in Philadelphia, in a Sept. 25 report to bond buyers. Schankel noted Puerto Rico bonds were sold by bankers, not just to "rich" Wall Street firms, but also to U.S. workers' pension funds and individual retirement accounts, as a way to enjoy U.S. public-bond tax exemptions while collecting higher rates than states paid.

Schankel said current talks overseen by the board and federal bankruptcy Judge Laura Taylor Swain call for trades of PREPA (power utility) bonds for new bonds at about a one-third discount; sales-tax, rum-tax, hotel-tax bonds and general-obligation bonds for new bonds at varying discounts; and water and sewer bonds for new bonds at much smaller discounts. Many of these bonds sell at below-par prices, even with discounts in the works, suggesting some final returns will be at fractions of original investment values.

In 2016, the PROMESA board was given three years to certify fiscal plans for Puerto Rico government agencies, end "accounting gimmicks" such as underpaying vendors, and end itself with enduring reforms in place, Skeel noted. When the island elected pro-statehood Gov. Ricardo Rosselló, the board, advised by a team assembled by former Ukraine Finance Minister Natalie Jaresko, demanded $1.5 billion in new tax revenues, $1.5 billion in government cuts, plus more cuts in college, healthcare, and elsewhere. Rosselló mostly agreed, and supported the board's plan to impose debt-payment cuts on an initial group of creditors. The board also called for a 10 percent pension cut, painful, but not a wipeout. Progress, board members thought.

"And then the hurricanes hit," Skeel writes. A year into PROMESA's mission, Puerto Rico was blown out by tropical storms Irma and Maria, leaving much of the island without basic services, killing an estimated 3,000 people, accelerating an ongoing flight of residents to the mainland, and incidentally strengthening the government's negotiating position by making it obvious recovery spending ought to be the priority — though it's often hard to tell that from the reported poor condition of many island towns a year later.

The board canceled its proposal to furlough government workers, and pushed for bigger debt discounts from bondholders. The board also pushed hard for "labor reform" that would let a privatized power company fire workers at will, which sounds like an ideological position in an industry where management failure, not labor cooperation, has been the most obvious problem.

Skeel notes some appointed financial overseers, like Detroit's Kevyn Orr, were greeted as villains but have come to be seen, with their success, as heroes. That hasn't happened for his gang, whose work is unfinished. Skeel says leftists call his board "a colonialist imposition" with a "catastrophic" economic agenda. Conservatives claim the board is not demanding full Puerto Rico government transparency, or deep-enough spending cuts, and that debt payment cuts will drive investors away from Puerto Rico.

The board's own numbers suggest the combination of debt-payment cuts and spending cuts will work. But as Schankel points out, it's the long-term structural reforms — finding healthy incentives for power company reform, tying future borrowing to sustainable sources of payment — that will keep Puerto Rico's future leaders from falling into the same hole.

That's a big job for elected officials everywhere.