Communal lifestyle reborn

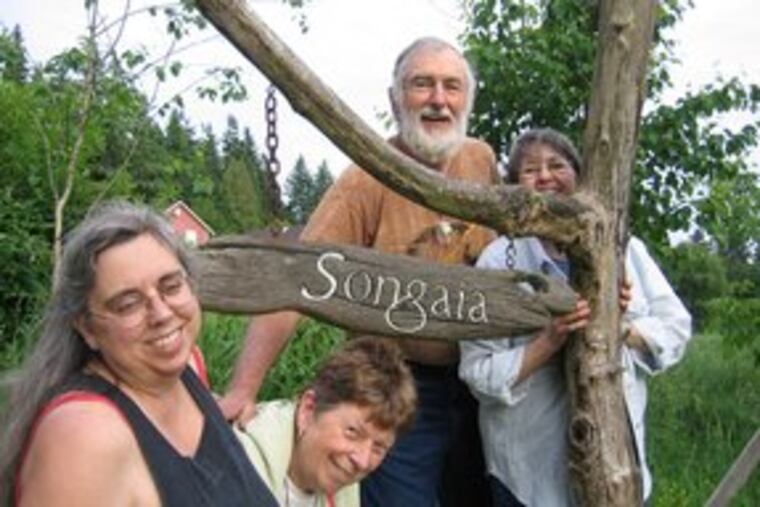

It's about 6:45 p.m. in Bothell, a suburb just northeast of Seattle, and the aroma of a buffet-style dinner fills the Songaia Common House. Three members of the community add finishing touches to the meal as about 30 neighbors fill the dining room, preparing to eat together.

It's about 6:45 p.m. in Bothell, a suburb just northeast of Seattle, and the aroma of a buffet-style dinner fills the Songaia Common House. Three members of the community add finishing touches to the meal as about 30 neighbors fill the dining room, preparing to eat together.

"I helped clean up after Saturday's breakfast," says Craig Ragland, 60, explaining why he did not have to help get dinner ready.

At cohousing communities such as Songaia, neighbors share meals several times a week. The neighborhoods, which mix private housing and shared community resources, facilitate close ties, as well as a greener way of life.

Grassroots promotion to Americans drawn to cohousing's energy-efficient, low-carbon lifestyle is a major reason the national market for such developments is suddenly growing, nearly 20 years after the United States' first cohousing community, Muir Commons, was established in Davis, Calif.

The attraction of leaving a smaller carbon footprint may lead to even more cohousing neighborhoods in the United States, according to a study published in the April edition of Journal of the Futures, an international publication devoted to society planning and futures studies.

"The lifestyle is very versatile - it can be done anywhere - hence the variety seen in the U.S.," says Jo Williams, a professor at the Bartlett School of Planning at the University College of London and author of the study "Predicting an American Future for Cohousing."

From Songaia, whose five main duplexes are nestled in 11 acres of hillside and meadow, to the apartment complexes of the two-block Eco-Village in Los Angeles, these communities adapt to their surroundings. They also appeal to people in varying socioeconomic classes, from the affluent to low-income families.

"About 50 percent of cohousing projects in the U.S. have focused on affordable housing and been successful at establishing it," says Charles Durrett, who with his wife, Kathryn McCamant, introduced the lifestyle to the United States in 1986 with their book

Cohousing: A Contemporary Approach to Housing Ourselves

.

Inspired by the communities founded 40 years ago in Denmark, "we wanted to accomplish a neighborhood that felt like a small town," Durrett says.

Today, at least 100 communities in 37 states, housing about 6,000 people, are in operation, up from just 60 communities two years ago. The majority of completed communities are in California, with 19 neighborhoods. Washington state has 13, and Colorado 11.

About 300 more cohousing communities are under development or initiated, says Ragland, executive director of the Cohousing Association of the United States. These homes are mainly owned as condominiums, although some rentals are available.

The collective housing has four main characteristics: a "social contact design," which creates a physical space conducive to a strong sense of community; common facilities such as gyms and kitchens; resident involvement in recruitment, establishment and management of the community; and a collaborative culture fostering interdependence, support networks, friendship and security.

Residents work together, first in the design and then in the operation of their own neighborhoods. Cooking and cleanup teams are on a rotating schedule, and maintenance tasks such as gardening and recycling are taken up by the community.

"In a cohousing community, there are expectations about sharing common resources, and for people who do not want to share, that's not a good fit," says Ragland. "People looking for cohousing tend to be focused on their values rather than their wants."

Lois Arkin, executive director of the nonprofit CRSP Institute for Urban Ecovillages, has lived in the Wilshire Center/Koreatown area of Los Angeles for 28 years. She spearheaded creation of the 162-unit Eco-Village there.

"It was a very blighted neighborhood" in the early 1990s, she recalls. CRSP had to retrofit the buildings, adding features such as environmentally friendly paint and flooring. "I also had to retrofit the neighborhood, which was ethnically divided," Arkin adds. "People were scared of one another."

Now, "it's a friendly environment in the middle of the crazy town of Los Angeles," says Somerset Waters, 30, who moved to Eco-Village in 2004. He and his wife, Aurisha Smolarski Waters, 35, hope to start a family, and they find the community environment the perfect setting.

Though some are wary of cohousing, believing it sacrifices independence and privacy, proponents say the arrangement offers a welcoming community

and

the privacy of your own home, when you want it.

"The secret ingredient to sustainability is community," says Durrett, and "the byproduct of knowing and caring for your neighbor is that the lifestyle can help the planet."