Formerly obese cardiologist recounts painful reaction - from colleagues

It is perhaps telling that Joseph Majdan waited until he was thin to vent his frustration at fellow doctors who made his life miserable when he was fat.

It is perhaps telling that Joseph Majdan waited until he was thin to vent his frustration at fellow doctors who made his life miserable when he was fat.

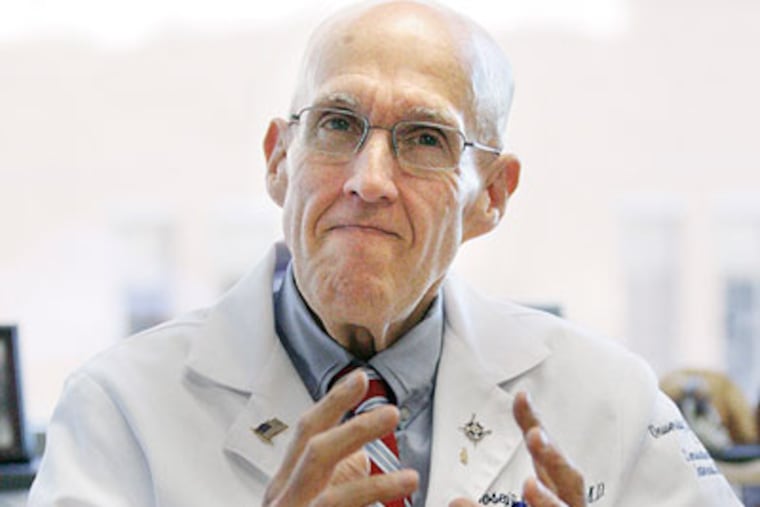

The cardiologist and assistant professor will say only that the poignant essay he has written for the Annals of Internal Medicine - "Memoirs of an Obese Physician" - was a long time coming.

"I've always thought about writing this article because it haunted me and it was a story that I think had to be told," he said last week in his office at Jefferson Medical College, where he was surrounded by pictures of his family, his dogs and of him when he looked twice as big as many of his friends. He said a combination of improved self-esteem and encouragement from his nutritionist led him to finally finish the article he started 10 years ago.

In his essay, he recounted a series of insensitive, even abusive, comments over the years from colleagues who seemed to have little understanding of obesity or compassion for those who struggle with it.

During Majdan's residency, a classmate at another hospital called to ask whether she could borrow his white intern pants to project slides onto during a skit. She said she thought it would be "hilarious." He thought it "insensitive and callous."

Jefferson's class of 1986 chose him as the subject of their class portrait, the highest honor a faculty member could receive. When it was done, another doctor told him, "You look too fat in the portrait. You know, they should only paint portraits of those who had done something worthwhile for the university. How could you with your size?"

He heard more than once of doctors who would not refer patients to him because of his weight.

Lest you think things have gotten markedly better, Majdan said a fellow doctor chastised him less than two years ago: "Aren't you disgusted with yourself?"

Majdan, 60, who would not disclose his weight, has won multiple teaching awards. He still sees patients and is director of professional development at the medical college. He works with medical students who are having interpersonal problems. He loves his job and he doesn't think that prejudice has changed his career path. But he does think that his colleagues' mean-spirited comments hurt his pride and lowered his confidence. He wonders how these attitudes affect the large numbers of patients who also have weight problems.

Majdan said he has great faith in the medical profession as a force for good. "I believe that this has to change, this prejudice toward obesity and obese patients, and I have such faith in the future of medicine that I think this has to be addressed," he said.

He said most people would never say such cruel things to someone of another religion or ethnic group. "Obesity lives in a politically correct free zone and is the last . . . prejudice openly accepted by society," he said.

He understands that doctors can be frustrated by their patients' failure to lose weight, but he sees it as no worse than many other difficult-to-treat diseases. "My fellow colleagues are understanding of cancer even when it recurs and recurs, and they'll say, 'Well, that's the disease,' " he said.

Ralph Schmeltz, a Pittsburgh endocrinologist who is president of the Pennsylvania Medical Society, said he is 40 to 50 pounds overweight and has always been on the heavy side. He said fellow doctors have not made hurtful comments to him and he doesn't know how common that kind of behavior is.

In 2003, Gary Foster, now director of the Center for Obesity Research and Education at Temple University, conducted a survey of primary-care doctors about obesity. More than half viewed obese patients as ugly and noncompliant. A third saw them as weak-willed and lazy.

Foster doubts that attitudes have changed much, although doctors might be more careful about what they say now. He doesn't think doctors are any worse than people in other jobs. "All professions share some core common beliefs and they tend to center on willpower and discipline," he said. Obese people themselves also have negative attitudes toward those who are overweight.

Tom Wadden, director of the Center for Weight and Eating Disorders at the University of Pennsylvania, worked with Foster on the survey.

He believes that researchers will eventually discover connections between genes and most severe obesity. Your weight is more complicated than how much you eat and exercise, he and Foster agreed. Different bodies burn calories at markedly different rates. That means that some people really do gain weight a lot easier than others. People who are seriously overweight may also experience hunger differently or respond more intensely to the taste of food than people who are not obese.

Neither thinks that doctors should be held to a higher standard because they're giving patients health advice.

That, Foster said, would reinforce the idea "that you can attribute somebody's skill as a physician, as a writer, as a singer, as a parent based on their body weight. It's preposterous."

Wadden thinks doctors should exercise and eat healthy food, but that won't guarantee they'll be thin. He thinks doctors who've had a hard time with their own weight are likely to empathize with overweight patients, and Majdan agrees.

Over the years, Majdan has tried lots of diet programs and he has succeeded more than once in losing lots of weight. But, like most people, he gained it back.

Majdan, who is 6-foot-3, says he is now at a healthy weight and has been on a maintenance program for almost a year. He would not say where his weight topped out, but the pictures on his wall show a very large man. Majdan says he would have been called severely obese.

He's keeping the weight down now with medical follow up; he's never done that before. He sculls and rides a bicycle. He eats the same food every day, starting with a breakfast of two egg-white omelets and tomato at the Melrose Diner. He never has sugar or bread.

In the past, he just kept quiet when doctors said things he found hurtful. He admired doctors so much that he took their criticism to heart.

He plans to speak up now. "Sometimes we have to teach other people how to treat us," he said. "From now on, I call them on it."