Larry Robin remembers the heady days of joining a then-edgy bookselling business, the days when visionary Barney Rosset, founder of Grove Press, published the scandalous Henry Miller and Tropic of Cancer, when Frantz Fanon and his Wretched of the Earth dominated political book talk on the left, days when there were 20 independent general bookstores in Center City.

When Tropic was banned, Robin's Books stood up to the ban and lost in court - eventually winning when the Supreme Court allowed Tropic sales in another case.

Rosset, the publisher, ripped off the hardcovers of his books and had them rebound in paper - the paperback revolution was turning bookselling upside down.

But then came the giant stores. Independent stores began to wither and die, unable to compete on price.

But Larry Robin continued at his store at 108 S. 13th St. - the third location for the family-owned business since its founding in 1936. Depression, war, boom, bust, porn shops, vacant buildings, revival, and restaurants - Robin's survived them all. Until now.

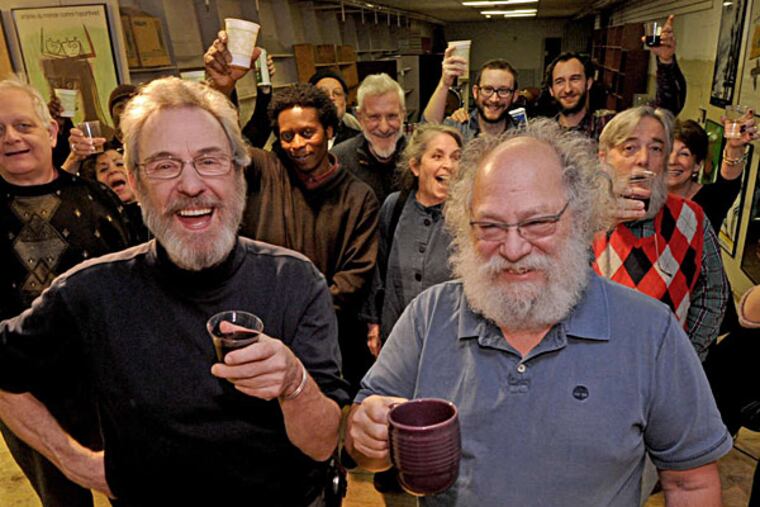

Saturday night, an official closed-forever, potluck party was held marking the end of 76 years in business for Robin's Books.

All the books are gone, the last batch sold to a book buyer from Chester County last week. Not since 1936, when Robin's grandfather David started the store on North 11th Street, soon to be joined by Larry Robin's father, Herman, and uncle Morris, has Philadelphia been without a Robin's Books.

(Herman died in 1998, although his ashes remained, in a gift-wrapped box, at the bookstore. His son happily showed them to a reporter Saturday night, saying: "He was always most at home in the store.")

So this was a party for a bookstore filled with empty shelves (plus a big bottle of vodka set prominently on a food table, next to the root beer and Dr Pepper).

Books may have been invisible ghosts hovering about the second-floor space, but 70-year-old Larry Robin was there, gray, bushy beard flaring out, like a maniacal and melancholy Santa, Red Zinger tea in hand.

His children and grandchildren were there; so were his colleagues and staff, present and past, and dozens of patrons and writers and artists, black and white, workers and intellectuals, poets, and, most of all, talkers and readers. (Also there was longtime manager Paul Hogan, who happens to be Inquirer columnist Trudy Rubin's husband.)

It was a great Irish wake of an affair, a celebration as much as a mourning time.

"I don't know what it signifies," said poet Elaine Terranova, thoughtfully chatting on the second floor of the 13th Street building. "But I wish it wouldn't close. Robin's means so much for Philadelphia. Larry has always been bigger than life."

The bookstore had flourished by fostering talk, all kinds of talk between all kinds of people; Robin's always tried to appeal to those who see the connections between books, ideas, beauty, culture, and the possibilities latent in a big, diverse city like Philadelphia.

In fact, conversation seems to sum up the Robin's experience.

"It's a cultural place," said artist Theodore Harris, whose works hung on the wall. "It's a cultural center. He's always trying to help people see how important writers are to our society. He's always about making literary art accessible to the people. It's a sense of community."

Larry Robin, his store finally snuffed out by the chaotic monopolization of the bookselling and book-publishing businesses, will certainly remain a presence in the city through the nonprofit cultural organization, the Moonstone Arts Center, at the site.

But the store is gone.

"I spent my life doing something I love," said Robin, surrounded by readers and writers. "You know how hard that is? Do you know how hard it is to go into your parent's business?"

Robin, who joined the family business in 1960, brought authors in to read. He founded an annual festival, the Celebration of Black Writing (now handed off to Art Sanctuary in North Philadelphia).

He showcased Philadelphia writers, women, political radicals. Maya Angelou, Jerry Adams, Sonia Sanchez, Eleanor Wilner, Walter Mosley, Terry McMillan, Rita Dove, and Charles Fuller were given a platform.

For Caity Shaffer, 22, who is a recent employee and is helping Robin put together a series of programs next month on the work of turn-of-the-century journalist, suffragette, and antilynching pioneer Ida B. Wells, said most of all she would "miss the customers" and "the interaction between a variety of different artists, different minds coming together."

Robin, she says, is unlike anyone she has ever met.

"He has a mind like a steel trap," said Shaffer. "He's able to transport himself to other times with real empathy and tell the stories of other people like they were his own."

at 215-854-5594 or ssalisbury@phillynews.com, or