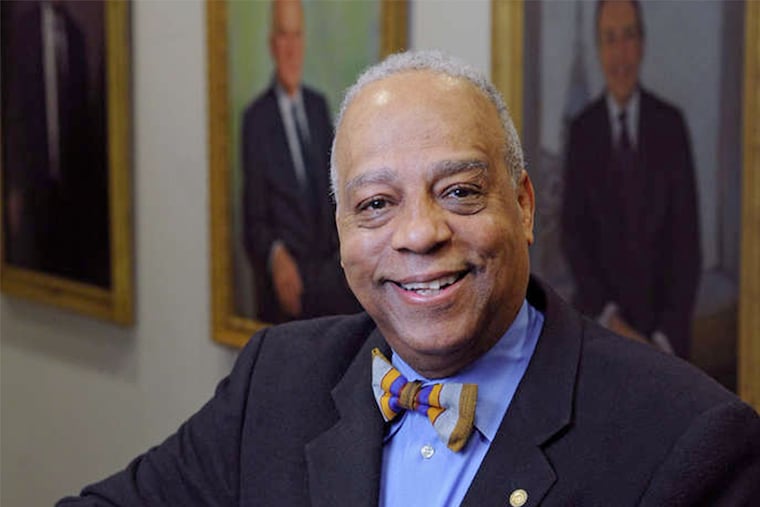

New head of the Philly bar focused on diversity

Even now, almost 45 years later, Al Dandridge can still hear the mortar and gun fire, picture the searing chaos of battle.

Even now, almost 45 years later, Al Dandridge can still hear the mortar and gun fire, picture the searing chaos of battle.

It was a perhaps-ill-conceived coin toss that led Dandridge to join the Marine Corps with childhood friend Christopher Billups. Billups had always wanted to be a Marine, and he insisted Dandridge go with him. Dandridge said no.

So they flipped a coin. Dandridge lost.

Sometime later, Dandridge, who will take over Jan. 1 as the new chancellor of the Philadelphia Bar Association, found himself in Vietnam. There, he served as a staff sergeant with the Fifth Marines at a fire base near Liberty Bridge, a key river crossing in Quang Nam Province, southwest of the huge American military base in Da Nang.

In the early morning of March 19, 1969, hundreds of North Vietnamese Army soldiers attacked, overrunning portions of the base. The attack, with small arms, flamethrowers, and mortars, caught the Americans by surprise, and many U.S soldiers scrambled from their sleeping quarters to sandbagged bunkers without rifles, even as heavily armed NVA soldiers were pouring through the security perimeter.

Moments after Dandridge had hurled himself into a foxhole, he looked up to see a North Vietnamese soldier firing his AK-47 into the bunker. The rifle was so close that muzzle flashes touched Dandridge's hand as he raised his .45-caliber handgun and, with one well-placed shot, dropped the enemy soldier. A man next to Dandridge had begun to cry.

The situation at one point became so precarious that American artillery officers trained their own howitzers on enemy targets - inside the firebase.

Dandridge would kill two other NVA soldiers in that night of battle, one while covering fellow soldiers scrambling back to their bunks to get their weapons.

"I am screaming at my guys, telling them to get the hell out of the bunker and get their weapons because we are in the fight of our lives," recalled Dandridge, a prominent Philadelphia securities lawyer.

At the end of the night, there were 12 American troops killed and 72 NVA dead. Dandridge would receive the Bronze Star, with a citation for valor. He says the lessons from that fight have stood him in good stead.

"When you are in it, you are in it," Dandridge said of dealing with crisis situations, including battle. "When you are under duress, and you are in it together, you are in it together.

"That is something that I have never forgotten."

Dandridge, an African American raised in West Philadelphia, gives his inaugural address Tuesday as the incoming chancellor of the 13,000-member bar association, and it is a safe bet he has one of the Philadelphia legal world's more singular resumes - along with some hair-raising tales to tell.

The dapper Dandridge may have started out as a grunt in the jungles of Vietnam, but he has since ascended to some lofty legal perches.

"When you grow up in Philly, you always have a nickname, and his nickname was 'Bubby,' and that is what I still call him to this day," said childhood friend Bernard W. Smalley Jr., a Philadelphia litigator. "He was always a guy who was very driven, very studious about what he wanted to do."

Following the tough fight at Liberty Bridge, the battalion commander named Dandridge to his staff as a kind of personal body guard. When Dandridge returned to the U.S. and was stationed at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, the Marines singled him out for training as a drill instructor, a high honor, and he was sorely tempted.

But he had an uncle who was a judge in Philadelphia, and Dandridge had set his sights on a legal career. That impulse led to law degrees from Temple University and the University of Pennsylvania, and a job as an lawyer in Washington with the Securities and Exchange Commission under Presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. Dandridge did two tours at the SEC, coming back to take a senior position during the Clinton administration.

He's now chair of the securities practice group at Schnader, Harrison, Segal & Lewis in Center City, and his clients run the gamut from finance to manufacturing. He is passionate about recruiting minorities and women, and he serves as the firm's chief diversity officer, seeking to encourage the advancement of underrepresented groups.

At big firms, Dandridge said, the problem isn't so much getting minority candidates in the door, but rather keeping them there. Too many times, he said, minority lawyers don't find their niche at big firms because more-senior lawyers fail to promote their careers. Data from the National Association for Law Placement makes the point. About 21 percent of law firm associates in 2013 nationwide were minorities, but the percentage was even lower in Philadelphia, 13.5 percent.

"Each organization has its own way of doing things, its own modalities, and when you get to these major firms," Dandridge said, "you need a fairy godmother or a fairy godfather."

As bar chancellor, Dandridge says, he will ask bar leaders to find ways to help minority lawyers forge careers. He says he will also push for individual members of the bar to reach out to young persons from poor and disadvantaged backgrounds and serve them as mentors.

"We tend to serve on boards, and that is important. We tend as a profession to do pro bono work, and that is important. We tend to write big checks, and that is important," he said. "What we don't do enough of is more hands-on service."