PhillyDeals: Assessing the House's financial-legislation agenda

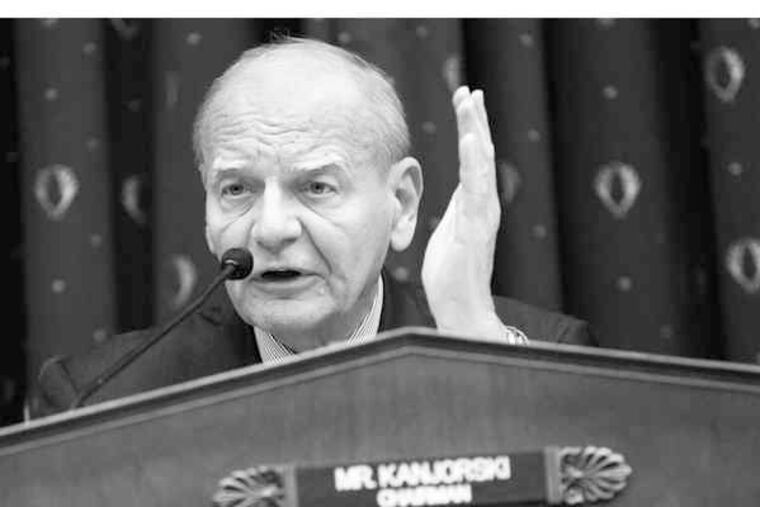

As Barney Frank, the Massachusetts congressman and chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, pushes President Obama's consumer and derivatives bills, Frank's lieutenant, Rep. Paul Kanjorski (D., Pa.), is wrestling the rest of the financial agenda toward the House floor.

As Barney Frank, the Massachusetts congressman and chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, pushes President Obama's consumer and derivatives bills, Frank's lieutenant, Rep. Paul Kanjorski (D., Pa.), is wrestling the rest of the financial agenda toward the House floor.

Kanjorski, taking questions from journalists last week, defended the compromises his fellow Democrats have made so far in four proposed laws concerning the Securities and Exchange Commission, credit-rating agencies, private-investment funds, and insurance regulation.

Here are the four pieces of proposed legislation, and Kanjorski's assessments:

The Rating Agencies Act (HR 3890). It should make it easier to sue Standard & Poor's, Moody's and other national rating agencies. It makes

credit-rating "internal operations" public.

Kanjorski, of Wilkes-Barre, is fond of blasting the agencies for their "almost criminal" blessing of the toxic subprime-mortgage bonds that brought down the financial markets last year.

Yet he and his comrades left intact the corrupt arrangement in which the big rating agencies will still be able to get paid by the companies they rate.

What's left in the bill "is not going to make ratings more transparent or more reliable," said Robert Dobilas, head of Horsham-based Realpoint L.L.C., a rating agency paid by investors and not by the people they rate. "It will cost us $500,000 a year" in additional compliance, Dobilas said.

"People do tend to favor those people who pay them," Kanjorski told me. "I wanted to remove that conflict of interest. But quite frankly, having talked to some of the most informed people, the agencies probably could not have funded themselves," he said, without cash from those they cover. "We'd be creating an even larger void."

The Private Fund Investment Advisers Act (HR 3818). It forces "all" money managers to register with the government and provide basic financial information so it can figure out if they're dangerous, Kanjorski says.

"There's an exemption for venture capital. We were very heartened to see that," Emily Mendell, spokeswoman for the National Venture Capital Association, told me. Lighter reporting requirements saves "hundreds of thousands of dollars a year" for each fund.

Mutual fund lobbyist Ianthe Zabel, of the Investment Company Institute, which represents Vanguard Group Inc. and other big fund companies, said carefully that the institute backed "robust comparable disclosure requirements" that cover "all financial products."

But fund executives complain this law goes easier on insurance salesmen than mutual fund distributors.

"I'm certainly aware of their dissatisfaction," Kanjorski told me. "We have not had the time, the effort, the ability to see that it's equal across the board."

The Investor Protection Act (HR 3817). It provides what Kanjorski calls the "crippled" Securities and Exchange Commission more power. It doubles its funding over five years. It subjects it to a "high-caliber" study to make sure the SEC is ready for the next Bernie L. Madoff. It offers cash to corporate informers, and allows the SEC to end mandatory arbitration so outraged investors can sue.

But accountants, facing pressure to make companies look better than facts may warrant, "want mandatory arbitration," said John McLaughlin, senior managing director at Devon-based Smart Business Advisory & Consulting L.L.C. "On complex accounting matters," he said, "you want an arbiter who understands the issues," more than a trial before jurors who might not.

The Federal Insurance Office Act (HR 2609). Right now, states, not the U.S. government, regulate insurance. Kanjorski's bill would set up a federal bureau to collect insurance data, help U.S. financial regulators weigh "systemic risk," and negotiate insurance treaties abroad.

"We saw, particularly with the collapse of AIG, we had no centralized expertise," Kanjorski said.

But state insurance departments smelled a power grab. Kanjorski "adapted the bill to some of our concerns," Pennsylvania Insurance Commissioner Joel Ario told me.

"The original language made it look like the federal government was going to build its own knowledge base," Ario said, "independent of what the states had." Now, according to Ario, the feds have agreed to work with data collected by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners - the state regulators who compile data produced by the companies themselves.