Wistar helps community college grads get hard-core science jobs

Is your idea of an apprentice someone who learns how to hang drywall and install windows? A new state-accredited apprenticeship partnership with Wistar Institute and the Community College of Philadelphia will apprentice technicians to leading research scientists, teaching them what they need to know to run a biomedical research labs in academic or industrial settings.

Amanda Moran, 26, spends her days in love with cells, research and science and in love with wearing a white coat and fighting cancer — not with fists up, but with her head bent down over a microscope.

"My mom died of breast cancer when I was 14," Moran said, taking a break at Wistar Institute, where her work as a biomedical technician helps in the basic science behind cancer research. "If I could, I'd like to help people not have to go through what I went through."

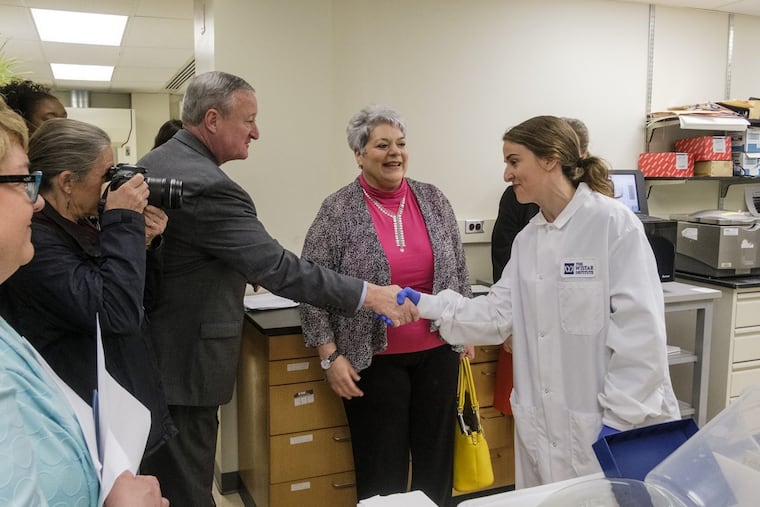

Moran was introduced on Tuesday to Mayor Kenney and Pennsylvania Labor and Industry Secretary Kathy Manderino as Exhibit A of the kind of person Wistar hopes to enroll in a first-of-its-kind apprenticeship program.

Apprentices in Wistar's program, which was just accredited by the state of Pennsylvania on May 11, will build on the institute's existing biomedical technician training to give apprentices more hours of on-the-job experience, as, and after, they complete an associate's degree at Community College of Philadelphia.

The program follows the traditional apprenticeship mix of classroom training and hands-on experience, but instead of apprentices becoming adept at hanging drywall and installing windows as they do in the building trades, they will be able to run laboratories as biomedical research technicians, working under the direction of scientists.

Moran and her fellow biomedical technician, Maya Thorn, 32, who talked to Kenney and Manderino about her research work on an HIV vaccine, are typical of the students that the program hopes to enroll. Moran worked for years as a waitress, and was financially independent at age 18. Thorn, an African-American, is an older student, and part of Wistar's push to bring more diversity to the sciences.

So far the program has just one apprentice enrolled — Nina Ibeme, 50, a Russian immigrant who studied chemistry in Russia, but never had the opportunity to apply her knowledge there. Wistar expects to shepherd three to five students a year through the program, recruiting them from the existing two-year biomedical technician training program that Wistar started 17 years ago. About a dozen participate each year.

The program was started by Wistar's director of outreach education and technology training programs, William Wunner, to solve a workforce problem at Wistar. The institute would train technicians, only to lose them to private industry, so the institute decided to develop its own technician pipeline. Wistar partnered with CCP, which provided classroom training and an associate's degree.

In the summers, Wistar would introduce CCP students to lab protocols. So far, Wunner said, 130 have gone through the 700-hour biomedical technician training program with about half staying employed in the field and the rest going on to higher education or into different fields. Of the graduates, more than half are minorities and seven in 10 are women. People in the program typically earn $10 an hour while in school, and $17 an hour as biomedical technicians in industry, Wunner said.

The new apprenticeship builds on Wunner's program, placing his graduates as apprentices with employers who will pay them as they train, building up 2,000 hours of lab practice. The Pennsylvania Department of Labor and Industry's involvement means that employers may be able to apply for on-the-job training funds that pay up to 50 percent of a worker's salary for a few months.

"From a finance perspective, I'd be crazy not to jump on that" and sponsor an apprentice, said Nicholas A. Siciliano, chief executive of Invisible Sentinel, a 50-employee Philadelphia company that has developed high-tech methods to detect foodborne pathogens.

Siciliano said years ago, his company brought in a biomedical technician who earned $15 an hour as an intern, specializing in manufacturing. "We fell in love with him" and he eventually became the manufacturing director, earning $60,000 before he left to pursue his doctorate, Siciliano said.

Anthony Green, vice president of Ben Franklin Technology Partners, said the biotech start-up community needs both the apprentices and the apprentice graduates. The biotech scientists in their small start-ups have the brains and the vision, but as they grow just beyond the fledgling stage, they need someone with biomedical research and technical skills to keep their labs running.

"These companies need help," he said. The apprentices "are also being trained to think. It's IT, it's big data, it's understanding that what they do today determines whether you are going to get a product out in the market in two years. That's a very different mindset from academic research."