Republican tax bill: GOP's reform is least effective for corporations

The tax bill's centerpiece is the massive cut in corporate taxes, from a top, statutory rate of 35% to 20% or 21%. Is such a large reduction in the corporate tax rate necessary? The short answer is that corporate taxes need to be lowered, but the current tax proposals do that in the least efficient way possible.

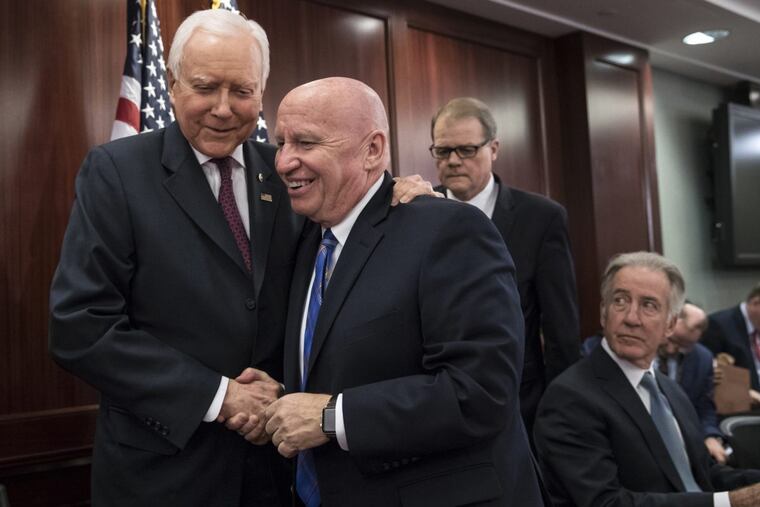

The tax bill is chugging its way through Congress and the differences between the House and Senate bills are being "reconciled" in a joint committee of House and Senate Republicans. The centerpiece is the massive cut in corporate taxes, from a top, statutory rate of 35 percent to 20 percent or 21 percent.

This raises a yet-to-be-discussed question: Is such a large reduction in the corporate tax rate necessary? The short answer is that corporate taxes need to be lowered, but the current tax proposals do that in the least efficient way possible.

First, let's address the issue of the level of the corporate tax rate. The statutory rate, 35 percent, is the equivalent to the manufacturer's suggested retail price, or MSRP, on consumer products. As the supporters of the tax bill have claimed, this is the highest rate in the world. When you add in the average rate for state and local taxes, it is nearly 40 percent.

But when was the last time you paid the MSRP for anything? Not often. And that is the case with the corporate tax. Factoring in deductions and other reductions to taxable income, the "real" or "effective" corporate tax rate drops to about 18.6 percent, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Now 18.6 percent is still one of the highest rates in the world, but it is half the rate our political leaders are using to argue for the huge corporate tax cuts. And even if other estimates of the effective rate, which range from about 22 percent to 26 percent, are used, it is still well below the 35 percent or the 39.8 percent rate that the bills' supporters like to assert.

So, when it comes to corporate tax rates, they are high, but they are not nearly as high as claimed. In addition, corporate taxes now make up only about 9 percent of total federal taxes, down from a high of 28 percent during the 1950s. And as a share of GDP, it is lower than the average of major economies. The corporate tax burden has already been sliced significantly.

The problem with the corporate tax centers more on its structure rather than its rate. The effective rate is an average and there are huge differences in the tax rates paid by individual firms as well as across industries.

Simply put, there are too many winners and losers created by the Byzantine tax code. Some companies have effective tax rates in 20s or 30s while others pay single-digit rates. Some firms, such as GE and Exxon recently, can generate so many deductions they wind up with negative tax rates.

After decades of financial engineering by politicians who sought to provide incentives to favored firms or industries, the entire code really needed to be scrapped and the inequities removed.

Economists call this restructuring of the tax code actual tax reform. The basic philosophy is that equals should be treated equally and that the tax code should create winners and losers infrequently.

Unfortunately, the current code discriminates and the proposed tax bills do little to change that.

What most economists say needed to be done was to broaden the base, and by doing so, generate revenues that would allow the statutory rate to be lowered. By doing it that way, the tax cuts cause budget deficits to rise as little as possible. The Republican tax bill has lots of tax cuts but little base broadening and a massive increase in the national debt.

To broaden the base, you need to eliminate tax deductions, loopholes, and the largely economically useless but politically popular tax scams that permeate the code. There are some deduction reductions, but many are on the household side, not the corporate side.

Worse, most of the cuts go to large corporations. The typical small business owner, who creates so many jobs, benefits minimally. Indeed, under certain circumstances, their taxes could rise.

And then there is the repeal of the ACA individual mandate, which has nothing to do with taxes. It is a way to reduce government spending so the proposals meet debt-increase limits. That spending cut would come from Medicaid. So, to fund, in part, the huge decline in the corporate tax rate, money is being taken from health care for the poor.

Yes, corporate taxes need to be reduced, but, even more important, loopholes and tax scams need to be eliminated from the code. If that had been done, the economy would have become more efficient. The tax bill that Congress is likely to pass fails abysmally to do that.