New twist on 'ugly overages'

Rick DeVirgiliis may be well past 50, but he's not totally out of touch. He and his honey text each other regularly, and not just sweet-nothings either. Useful stuff, too, befitting their busy, two-career lives. Stuff like, "Did you feed the dogs?"

Rick DeVirgiliis may be well past 50, but he's not totally out of touch. He and his honey text each other regularly, and not just sweet-nothings either. Useful stuff, too, befitting their busy, two-career lives. Stuff like, "Did you feed the dogs?"

What they don't do, DeVirgiliis says, is "TM each other all day like a pair of adolescents." That's why he and fiancée Eileen Kerrigan were surprised recently when Sprint charged them an extra $63 for text messages beyond their 300-apiece allotments.

Sprint dunned them for an extra 318 texts to be exact - enough to nearly double their usual family-plan bill.

Getting burned by blowing through your plan's limits is old news in the wireless world, where Sprint ads once popularized the phrase ugly overages. But what astounded the Oreland electronics technician is what happened next.

DeVirgiliis wanted to adjust before he got burned again. So he requested an itemized bill, for just that one month. No need for paper - an electronic version would do.

Sprint's answer? An emphatic no.

DeVirgiliis says he got various explanations as he escalated his complaint. He says one Sprint staffer told him, "The FCC won't allow it." Another said, "No other company will provide that information." It wasn't hard to disprove either excuse. "I've seen my daughter's AT&T bill," he says.

Finally, he says, a letter to Sprint Nextel CEO Dan Hesse drew an executive-level response: an e-mail telling him that Sprint wouldn't provide the text-message records without a subpoena, and inviting him to cancel his service - albeit with an early termination fee of $200 per phone.

DeVirgiliis suspects the worst. "I can only conclude that they are hiding something," he says. Pad just a dollar a month onto 49 million customers' bills, he says, "and pretty soon you're talking real money."

DeVirgiliis believes, quite reasonably, that access to an itemized bill is a basic consumer protection. If you're going to be charged, you're entitled to know what you're paying for. He likens Sprint's policy to getting a restaurant check "for $127 in charges for 'food, drinks, and tax.' How could you know it was right?"

My own calls to Sprint officials brought a slightly different answer.

Yes, a customer who wants to see the text-message itemization has to contact Sprint's "Subpoena Compliance Group." But if the request isn't part of a legal proceeding, no actual subpoena would be necessary. A notarized form will do - an option not mentioned to DeVirgiliis.

Still, why the big hurdle for what other companies treat as routine information?

"Sprint has made a business decision not to provide text-message detail on our invoices, due to privacy concerns," wrote spokesman Scott Sloat.

I asked for clarification, but never quite got it. Sprint's Roni Singleton said the content of a text message would never be released, except under subpoena, but couldn't say why the date, time, and sender or recipient's phone number should be more private than a call record.

"We're exploring some options for self-service in the future," she said. "It's not something we've had a lot of requests for."

Though I understand DeVirgiliis' suspicions, I don't share them. Sprint doesn't need to cheat on text-messaging. It's already making out like a bandit on the deal - as are its competitors.

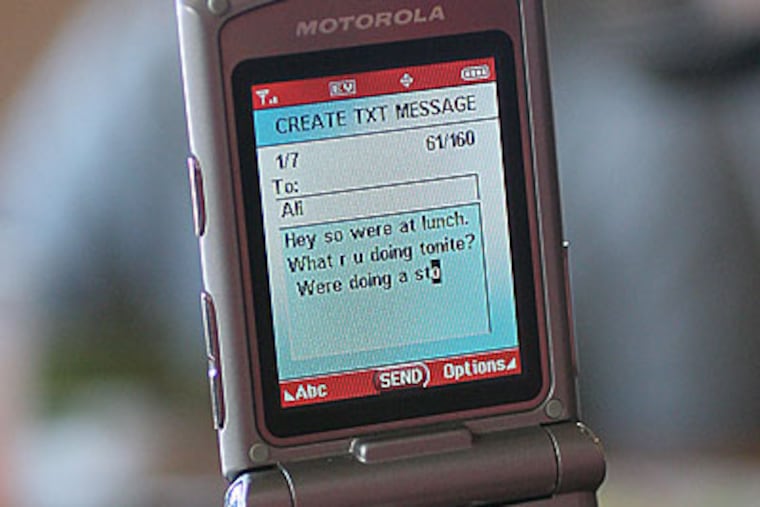

Text messages are an astonishingly profitable sector of the wireless business. With their 160-character limit, texts use a tiny amount of bandwidth. And although most texters eventually buy plans that lower the average cost, since 2005, the major U.S. carriers have all doubled their single-text charge to 20 cents - behavior that has brought increased scrutiny, congressional hearings, and a price-fixing lawsuit.

In testimony last month to Congress, Consumers Union policy analyst Joel Kelsey said U.S. wireless customers paid an average of $506 a year for service in 2007, compared with $374 in Britain and $293 in Spain - countries where, not coincidentally, a "calling-party-pays" rule means that a text or call is billed just once. In the United States, a message from DeVirgiliis to Kerrigan is counted twice, even though calls between them are free.

To keep their bills in check, Kerrigan was talked into an extra $5 a month for a $10 plan that allows 1,000 texts. In other words, she'll pay a penny apiece if she uses all of them.

As Kelsey puts it, infrequent text users are paying protection money, just in case their family or friends get a little too text-happy.

The carriers are saying: Sign up for a text plan, or you'll pay for it in the end.

If you recognize the author's name on this column, there may be a reason. From 2001 to 2006, I wrote the Inquirer's "Consumer Watch" column.

Since then, the marketplace has changed considerably, mostly because of the collapse of the housing bubble and the recession. Some hazards are gone, such as the trickiest adjustable-rate mortgages. But others remain, or have worsened, as companies squeeze out revenue wherever they can find it. Text messaging is one example.

In the weeks ahead, I hope to explore other aspects of the marketplace from a consumer's perspective. To that end, I have one request: Tell me about your experiences - the ones that please you as well as the ones that worry you or drive you crazy.

As any economist will tell you, markets work best for knowledgeable participants. The 2009 marketplace is full of rocky shoals, and the goal of Consumer 9.0 is to help you navigate.