Another tool for parents of networking kids

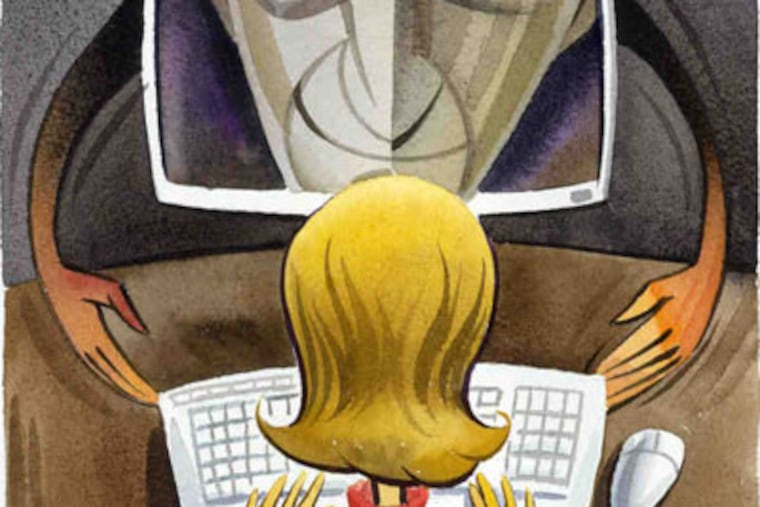

As any parent can attest, kids and technology make for a confounding mix. Let's face it: Sometimes, it gets a little scary.

As any parent can attest, kids and technology make for a confounding mix. Let's face it: Sometimes, it gets a little scary.

What are your children and their friends doing and saying online? What are they posting on Facebook? Texting on their cellphones? Tweeting on Twitter? Are they worried - or should they be - about cyberbullies or online predators?

If your kids have access to the Internet or cellphones, as most do, those questions prompt real concerns.

But deciding how to address them raises another question: What's the boundary between good parenting and overbearing intrusiveness when options range from giving advice to buying spyware that logs a child's every keystroke?

There's no one-size-fits-all answer - not in an era when teenagers face life-threatening risks and even some kindergartners go online. Nor is it time to stick your head in the sand - not when Facebook has an estimated 7.5 million preteen users, even though they are supposedly ineligible for the popular social-networking service.

There are technological approaches aplenty for parental control and monitoring. Last fall, PC Magazine scoured the field and found dozens, naming nine as "Editor's Choices," including Net Nanny, Bsecure Online, and Web Watcher - a full-scale spyware program for the most anxious of parents or bosses.

On Thursday, a Philadelphia-area company, Blue Bell's PredictivEdge Technologies L.L.C., plans to introduce a new contender that aims to protect children without venturing into parental espionage: the Proactive Parenting Network.

I recently had the chance to poke around a beta version of PPN, as the company calls it, and to speak with chief executive officer William M. Thompson and Keith Harry, senior vice president for product development. They say their aim is to help parents cope openly and honestly in an era when, as Thompson puts it, "kids are the IT professionals in the house," and might well be able to dodge a more heavy-handed approach.

One key to PPN's value is its natural language processing software, which they say is able to go beyond simple keyword analysis and generate alerts for real risks or dangers with fewer false alarms.

For instance, "I hate the Mets" won't cause concern. But "I hate you" will - as a potential red flag for cyberbullying, or at least for a subject that a parent might want to bring up.

PPN doesn't try to do everything. For instance, it doesn't oversee your child's Web surfing, or block potentially disturbing Internet content such as explicit violence or sex - perhaps the primary online risk for younger children, according to Stephen Balkam, who heads the nonprofit Family Online Safety Institute.

Instead, PPN aims its firepower at children's increasing use of two leading social-networking sites: Facebook and Twitter. Later this year, the company hopes to add the capacity to scrape and examine cellphone text messages, and alert parents when their children's texts raise concerns.

Despite its narrow scope, PPN may be well-adapted to the concerns of today's parents, compared with their counterparts of that distant era a decade ago when my children were young and objectionable content on websites was a major worry.

"Basically, kids are now putting up on the Web the kind of content we were trying to keep away from them," Balkam says. "And they're doing it on the move, thanks to their mobile phones."

So how does PPN work? Thompson says parent-child cooperation is a key, since to allow monitoring, children either need to provide social-network passwords directly to their parents, or respond to an e-mail requesting their participation.

PPN provides a wealth of free online-safety information and videos through a partnership with i-SAFE Inc., which calls itself "the leader in e-safety education," and a licensing deal with the Mayo Clinic's highly regarded health-information website.

Monitoring services cost $10 a month, which the company plans to waive at the start. For that, parents can receive alerts triggered by profane, racist, or sexually explicit words, or language that suggests risks of cyberbullying, suicidal thoughts, eating disorders, violence, disclosure of personal information, and other common concerns. At the same time, PPN's image-recognition software can flag nudity in photos.

PPN's developers concede the difficulty of screening messages tapped out quickly in a continually evolving vernacular.

"Let's go shoot up" generated only a violence alert for the word shoot until the software was taught drug users' slang. Thompson says the system was taught to recognize doritos as a regional slang word for beer, and vodka eyeballing as a dangerous activity in which alcohol is poured into the eyes, perhaps to get high or perhaps simply as a stunt.

Harry says natural language processing enables the database to adapt - in essence, to learn as it goes along. "Vigilance to the changes in language is critical," he says.

Thompson says PPN's goal is enabling parents to stay similarly vigilant about dangers they might not even recognize, and help them build bridges in tricky terrain. "We want the parents to have a conversation with their child - to sit down and tell them why they are doing this, and what are the risks."