A statue of Jersey Joe Walcott, Camden’s real-life ‘Rocky,’ to rise in the city he championed

A $15,000 gift from the Holman Foundation has enabled project organizers to hire the celebrated sculptress Vinnie Bagwell to begin work on the statue.

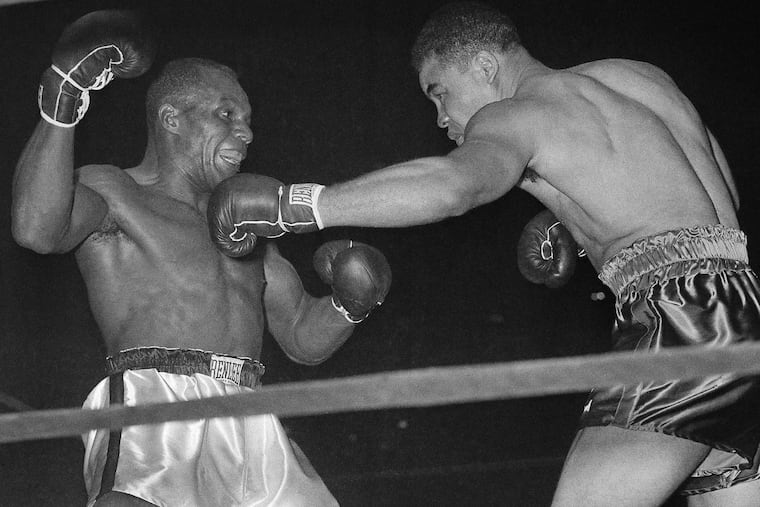

A larger-than-life bronze likeness of Jersey Joe Walcott, the beloved boxer who won the world heavyweight championship in 1951, is envisioned as a centerpiece of a proposed sculpture garden in Camden.

"It will be a symbol of a city that's fighting back," said Vincent Cream, the oldest grandson of Walcott, whose given name was Arnold Cream.

The esteemed fighter died in 1994 at age 80 and is still remembered by many in the city and beyond as a formidable force in the ring, as well as in the community.

In my estimation, this honor is not only due to Jersey Joe — it's also overdue.

"My grandfather fought for 21 years," said Cream, 58, a salesman who lives in Pennsauken. "He fought through the Depression, while he was working other jobs, and he was older and had more losses on his record than any other heavyweight champ when he won the belt.

"He's an example of faith and determination and perseverance, and the statue will be a magnet for students and will connect people to his legacy. It will be a combination of education, and inspiration."

Family members have been working on the project with the Camden County Historical Society since March. A $15,000 grant in May from Holman Enterprises, in Mount Laurel, jump-started the effort, and a fund-raising campaign for what is estimated to be the $100,000 total cost of the statue is set to begin this fall.

Separately, the sculpture garden itself has been in the works for two years and also will include a display of architectural features salvaged from the recently demolished Camden High School. The garden will be built on the south side of the historical society's Park Boulevard campus in the city's Parkside section.

"The location is near the Camden High football field and it's ideal — the athletes will see it as they go by," said Sheilah Greene, a longtime Parkside resident and Cream family friend who is involved in the project.

The site also is significant because Pomona Hall, the Cooper family plantation house that is preserved as a museum, was home to several enslaved Africans. The society is talking to sculptor Vinnie Bagwell about a second bronze to honor them, as well, board president Chris Perks said.

Bagwell, known for public sculptures depicting African American luminaries such as Ella Fitzgerald and Marvin Gaye, is first designing a maquette, a small-scale version, of what is to be an eight-foot bronze of Camden's champ.

"This is a portrait commission, so I need to see as many likenesses of him as possible. I look for what I call power images, images that have energy," Bagwell said from Yonkers, N.Y., where she has a studio.

Like the boxer's career — lovingly recounted on the Camden-centric website dvrbs.com — efforts to create a permanent memorial to the fighter have been characterized by years of struggle.

Earlier proposals called for erecting a statue on the Camden Waterfront or at Sunset Memorial Park in Pennsauken, where Walcott is buried. "A lot of ideas have been in the pipeline and haven't come to fruition," Cream said.

But the South Jersey poet and historical society board member Sandra Turner-Barnes' suggestion last fall that such a statue should be part of the proposed sculpture garden provided a lightbulb moment, said Jack O'Byrne, the society's executive director.

Turner-Barnes, who remembers Walcott talking to Camden youngsters at the schools and on the streets during her childhood in the city, noted the popularity of Philadelphia's statue of Rocky, the boxer played by Sylvester Stallone in the mega-movie franchise.

"People come to Philadelphia, and seeing the Rocky statue is one of the first things on their list," she said. "That's all well and good. But Rocky is a fictitious character, and in Jersey Joe, Camden has a genuine hero. He was the world champion and he was also the champion of our community."

Walcott grew up poor in Merchantville. As a boy, he was recognized by family members for his boxing abilities, as well as his fleet feet and personal magnetism.

"He told me the story of being 8 or 9 years old and hearing his father tell his mother he could be the world champion some day," Cream recalled.

Walcott began boxing professionally as a teenager but barely made a living from it until relatively late in his career. He became famous for knocking down Joe Louis — three times — and on his fifth try for the title he defeated reigning champ Ezzard Charles during a bout at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh on July 18, 1951.

After losing the world heavyweight title to Rocky Marciano in 1952, Walcott went on to become the first African American to serve as the sheriff of Camden County.

His second wife, Riletta Cream, became principal of Camden High after a period of turmoil there in the early 1970s. Walcott was an imposing, and calming, presence during athletic events at the Castle on the Hill.

"He was universally respected and internationally known," said Vincent Cream.

His grandfather's admirers included "presidents and popes," as well as Frank Rizzo and J. Edgar Hoover, he said.

There are numerous tributes to Walcott on YouTube, several of them celebrating not only his powerful fists and technical skills, but the fluid grace of his footwork.

"Jersey Joe was a dancer," said Bagwell, who wants the sculpture to "tell the story" of Walcott as a person, as well as a professional.

"It's meant to be a monument," she said.

"But I want people who see it to say, 'that's Jersey Joe.' "