Why Philly's crumbling libraries aren't just libraries anymore | Mike Newall

In Philadelphia, it's becoming increasingly clear that libraries are not just repositories - they're dynamically responding to the needs of the people they serve.

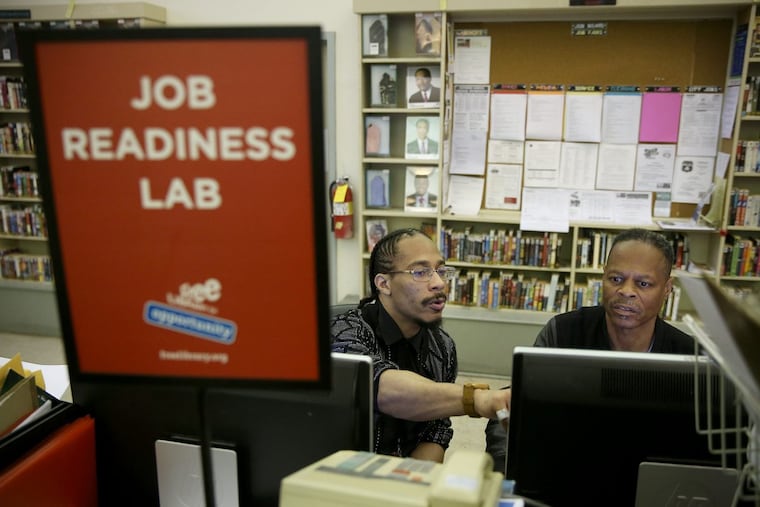

In a 103-year-old library in Southwest Philadelphia, where the roof is leaky, the windows are drafty, and the heating and cooling system is as finicky as an old crank, three men sat under dull lights at a bank of computers, trying to land a job.

Omelio Alexander peered over their shoulders, adjusting a resumé line here, helping navigate a jobs website there. His title at the Paschalville branch is "digital resource specialist," which, here, means that his job is to help people find work in a community that desperately needs it.

In Paschall, the surrounding neighborhood, the unemployment rate is 17.3 percent. In the entirety of the city of Philadelphia, it's 5.8.

If the role of the library is to meet the needs of the community, Alexander can sum up the needs of this one in three words: "Jobs, jobs, jobs."

He runs the Job Readiness Lab there, the only one in the Free Library's 55 branches. Under his charge are three computers, set apart from the others, reserved for people looking for work.

Men and women looking for a better opportunity. Residents of the homeless shelter down the street. People returning from prison, trying to overcome the gaps in their resumés and the conviction on their records. Alexander maintains a cache of neckties for job applicants to borrow for interviews.

For some people who come in, the hardest part of the job search is filling out an application.

"Some of it's just physical — using a mouse, navigating the keys, how to look for what you're supposed to be looking for on a screen," Alexander said. Sometimes he helps with typing and capitalization. "If [employers] see any reason not to look at your stuff," he emphasizes, "they're not going to read it."

The jobs lab is one of the frontline programs in Philadelphia that are expanding the notion of what a library is and what it means to the community it serves.

"We need a redefinition of the word library" as something beyond just books, said Siobhan Reardon, the Free Library's president and director. "Because we happen to be in most cases the singular civic entity in a lot of communities."

The debate boils down to this: "What is a city library?" Reardon asked. In Philadelphia, it's becoming increasingly clear that they are not just repositories — they're dynamically responding to the needs of the people they serve.

We saw that plainly — perhaps more visibly than anywhere else in the country — a year ago this week, when Chera Kowalski, a librarian at the historic McPherson Square branch in Kensington, began saving the lives of overdose victims on the library lawn. The need among people in the heart of the city's opioid crisis was simply to stay alive.

What happened at McPherson was dramatic, but not an outlier. It's part of a philosophical shift playing out across the country.

It's a conversation I'll be writing about this summer, as I visit the libraries that lend much more than books to their communities.

It's a conversation that's becoming increasingly urgent in a dynamic city still marked by some of the worst poverty in the country. And then there's this stunning statistic: Half of working-age Philadelphians, about 550,000 people, lack "workforce literacy skills," and struggle to fill out job applications or follow written instructions.

It's a conversation that's happening inside crumbling buildings across the city that desperately need the repairs that the city's Rebuild initiative is promising.

Paschalville is at the top of the list; the branch was closed for a month in 2016 for a broken heater. It needs work "from top to bottom," said Jim Pecora, the Free Library's vice president of property management.

But that initiative is in danger of becoming mired in Philly politics.

City Council members have rightly raised the alarm over the need to enforce minority inclusion in the building trade unions, whose members will be repairing those struggling libraries and rec centers — and it's refusing to give the go-ahead for the construction until they're satisfied.

Mayor Kenney has vowed to plow ahead with the funds he has, saying the deal that he and union boss Johnny Dougherty have worked out is final. He's rightly argued that we need to act before the libraries become uninhabitable.

If one thing is clear, it's that both sides — both of which are raising legitimate concerns — need to get to the table. Now. It's not that we should be sacrificing minority jobs for library repairs, or vice versa. It's that we need to come to compromise before we further endanger programs that are helping some of the city's most vulnerable.

On Wednesday, Sonkarley Duo, a Liberian immigrant with a degree in business administration, sat at one of Alexander's computers at the Paschalville branch. The 54-year-old father of two got weary of his last job, on the graveyard shift at a T-shirt printing company that he had to take four buses to reach.

He was looking for something better. And he had come to the library to do it.

Alexander peered over his shoulder. "He's my teacher," Duo said, smiling.