Monica Yant Kinney: Insurance plan no longer sweet

Clyde Schell realizes he's a throwback, having retired at 56. He doesn't regret it, but he might have done things differently had he known that his freedom would leave his wife uninsurable, with cancer.

Clyde Schell realizes he's a throwback, having retired at 56.

He doesn't regret it, but he might have done things differently had he known that his freedom would leave his wife uninsurable, with cancer.

Schell spent 30 years as a maintenance machinist at Tasty Baking Co. He fixed ovens and built conveyors, helping the factory churn out the Butterscotch Krimpets he devoured as a boy in West Oak Lane.

Schell saved aggressively and hired a financial adviser, enduring ribbing for his obsession with retiring on his own terms.

"I wanted to be in control of my life," he explains, "rather than having the company control me."

And yet, four years and 400 miles removed from the past, the West Chester-to-North Carolina transplant finds himself again beholden to his old bosses. Because Tasty Baking, like many companies, is dropping pre-65 retirees like Schell from its health plan.

Working to live

My grandfather, a machinist like Schell, retired from General Electric at 60. Twenty years later, my dad quit teaching at 56. Both seemed too young to do nothing, but I admired their resolve to relax.

When my mom celebrated her 65th birthday last month, I sent her flowers at the office. Unofficially, she's working to pay for new windows. The real reason she suits up each day? Health care.

"Many people are ready to go at 58, they just can't afford insurance," notes Temple University health management professor Thomas Getzen.

"At 55, it's going to cost you a lot of money for inferior coverage - and that's assuming you're healthy and can find anyone to take you."

Only a third of all companies still offer health care to former employees during the crucial period before they turn 65 and can qualify for Medicare. Even employers that do often break the promise to bolster the bottom line.

Princeton health-care economist Uwe Reinhardt harbors little sympathy for young retirees like Schell who "have only themselves to blame for believing in these rickety promises."

Wharton School professor Mark Pauly - who's still working at 68 - also offers a frigid reality check: Health care for retirees "was always a business decision, and business has changed.

"If you thought your company loved you, you were wrong."

Lost in transition

When Schell left Tasty Baking, he opted to remain on the company's health plan. He paid mightily for it, $1,100 a month, but had peace of mind when his wife, Martha, needed a hip replacement.

Now, the 875-employee snack company says it has no choice but to drop all 45 "young" retirees.

"This was a small group," David Vidovich, vice president for human resources at Tasty Baking, says. "They spend a significant amount of money," presumably on things like hip replacements.

Schell, a robust 60, found a reasonable private plan. But his 59-year-old wife was deemed untouchable - rejected first for the hip, then for multiple myeloma, cancer of the bone marrow.

Martha Schell can go on COBRA for 18 months, but then she'll be 61 - four long years away from having Medicare help with cancer's cruel costs.

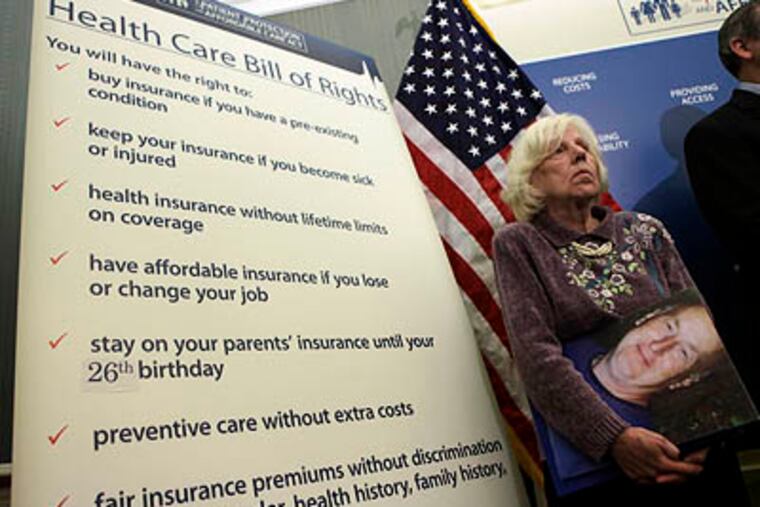

It could be years before the couple could benefit from health-care-reform proposals such as the prohibition against insurance companies' shunning people with preexisting conditions, and the latest compromise to a public option: allowing a Medicare buy-in for folks 55 to 65.

Barring swift passage of any meaningful change, Martha Schell's best bet is also her worst: Become so sick so quickly that she qualifies for Social Security disability and Medicaid.

So much for Clyde Schell's relaxing retirement. After making the biggest decision of their still-young lives, "we're left with no choices." Suddenly, work seems like a welcome distraction.