"Class Acts": Teacher puts on a Polymer Pageant to reveal beauty of chemistry

One afternoon last week, students at Central High School were fussing over their posters, PowerPoints, and costumes as an unusual competition was about to begin.

One afternoon last week, students at Central High School were fussing over their posters, PowerPoints, and costumes as an unusual competition was about to begin.

"Some people are looking fantastic in plastic," said Schuyler Patton, welcoming his material science class to the third annual Polymer Pageant.

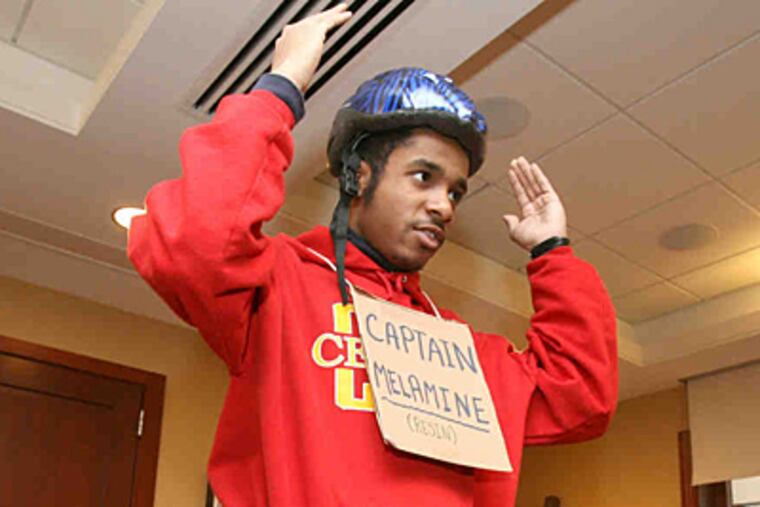

Ali Miller, 16, was wearing a blue helmet on his head. Hanging from his belt were Ziploc bags full of Eucerin moisturizer, along with cheap bowls and utensils.

Across the front of his red sweatshirt was a sign with the words Captain Melamine (resin).

"It's set up like a Miss America pageant," said Patton, who invented the kooky project to help his seniors learn about the macromolecular materials in everyday plastic items - everything from toothbrushes and combs to credit cards, raincoats, and tires.

Students are challenged to "give the polymers a personality based on their properties," he explained, and each student must demonstrate why his or her assigned polymer "deserves to win the 2011 Ms. Polymer crown."

Eager to talk about his polymer, Miller told the class that in the 1950s, melamine resin replaced ceramic as a cheaper material for making bowls and utensils.

Helmets are also made from melamine resin, which, Miller explained, emits an odor when the helmet cracks - a warning that it's no longer as protective.

"The bigger the crack, the more it will stink," said Miller, who plans to study mechanical engineering next year at Drexel, if he receives enough scholarship support to make it affordable.

Despite his enthusiastic participation in the pageant, Miller said that he has trouble being creative and had to solicit the help of his mother. "Personally, a textbook is more me," he said.

Yanni Mai, 17, isn't sure whether science is in her future - she signed up for Patton's class as a way to test her interest - but as a Philadelphia Eagles fan, it was easy for her to get excited about her polymer.

Polyisobutylene makes the airtight inner lining for sports balls.

"Without polymers, football wouldn't even exist!" said Mai, who couldn't get her hands on the waterproof butyl tape made from it. Instead, she constructed an outfit out of duct tape and garbage bags and wore that instead.

For Mai, the Polymer Pageant was a divergence from the "traditional sit there and read your book and ask some questions" approach to learning, a chance to flex different brain muscles.

"This allows me to learn in my own way."

While Patton's pedagogy includes textbooks, he deems them insufficient on their own. Patton tends to fill in information that he feels the books leave out - such as the importance of considering the costs of different materials such as metals, woods, or plastics and the trade-offs involved in picking one over another.

Patton also supplements the textbook with creative projects like the pageant or a cooking show, which will highlight the thermal properties of the materials the class has studied - metals, ceramics, and polymers.

Studying polymers textbook-style, he said, doesn't leave students with "nearly the retention that they would get out of a project like this . . . it gives things a unique perspective."

Science students may be thriving at Central High, one of the state's top-rated schools, but much of the country could use some help. A recent assessment by the National Center for Education Statistics reported that fewer than half of U.S. students show proficiency in science, with only 21 percent of 12th graders performing at or above the proficient level.

Patton, 31, a Bucknell University graduate who hopes to complete a master's program in chemistry education at the University of Pennsylvania by summer, knows that his course - not to mention his approach - isn't included in the conventional high school curriculum. He thinks it should be.

"I'm willing to bet that there are less than 10 high schools in the country that teach material science," he said.

Patton brought the course to Central High School three years ago after he noticed that his students most enjoyed the parts of chemistry that had real-world applications. "No matter what field students get into, this is applicable," he said.

At the pageant, students paid close attention to each other's presentations so they could cast their votes and also prepare for a quiz.

Mai perked up when one student boasted about the merits of his polymer, polyvinyl acetate, a component of glues.

"It has a good finish," he said.

Mai quipped, "I need a guy like that!"

Everyone around her laughed - and then went back to taking notes.