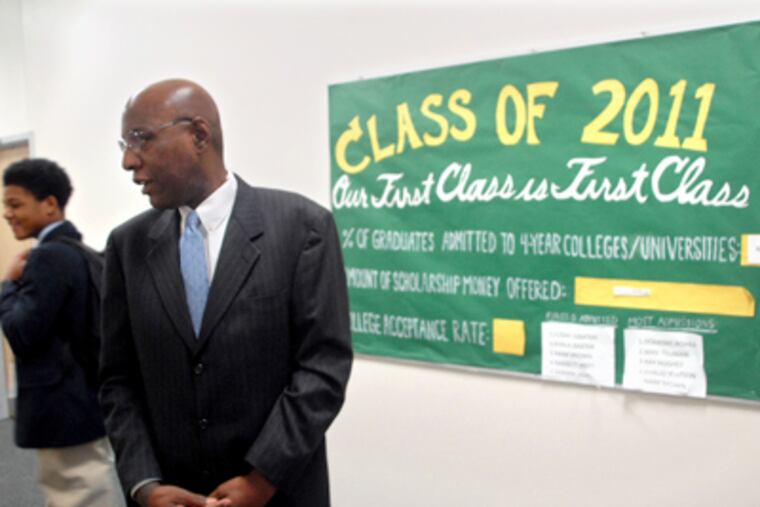

Keeping standards high at Boys Latin

David Hardy believes every young man at Boys' Latin is "the architect of his own fortune." But to build that future, students must first pass inspection.

David Hardy believes every young man at Boys' Latin is "the architect of his own fortune." But to build that future, students must first pass inspection.

"Hat off, sir!" a gatekeeper barks at an entering student, who quickly tucks the contraband away. "More walking, less talking," stragglers are cautioned.

On this bright, cold Friday, boys have traveled from as far as an hour away to this tattered West Philadelphia neighborhood, wearing navy blazers, oxford shirts, ties, tan pants, and name tags.

"You've got on white socks," one student hears, sent to the office for black ones. Another is called out for a brown belt.

Every student, the Boys' Latin uniform insists, is held to the same high standard. The school also embodies Hardy's vision of getting more boys, particularly African American boys, into college.

As the school's chief executive officer, Hardy, 59, fights an uphill battle. Whether blocked by listless parents, bare-knuckled poverty, shoddy schools, or all of the above, only about four in 10 African American boys in the city graduate from public high schools, a reflection of a national education crisis.

In June, at Boys' Latin's first graduation, the entire senior class will receive diplomas. More than half of the 82 boys have been accepted to college, winning more than $800,000 in scholarships.

Hardy aims for 100 percent - and to somehow pull up those underclassmen who lag behind, some of whom read at an elementary school level.

But striding down a hallway of beautiful student artwork, moving historical quotes, and colorful college flags, Hardy has immediate business with a sophomore who trails behind him.

The boy has earned one demerit and an hour, starting at 7 a.m., to ponder whether thwarting the dress code a third time was worth it.

Hardy pivots, thinking, "That boy is going to have a hard time here."

Hardy designed the school to be rigorous. Boys study Latin for four years, an analytical language proved to raise SAT scores. There are no girls to show off for, classes end at 5 p.m. three days a week, and Saturday school is offered twice a month.

"It should be a serious academic environment," Hardy says, "because if it's not, it's Animal House."

School must be an active enterprise for boys, Hardy says. They need to build things and take things apart. They need to be academically engaged. When they're not, they compete on everything, such as who can punch the hardest. They need challenges.

"The thing is," Hardy continues, "students hardly get anybody to tell them the truth. Kids do mediocre work, and we say, 'Oh, that's wonderful.' We need kids really achieving, because otherwise when they get out in the world, they fail real challenges."

Imposing

Walking the halls, Hardy, a lean 6-foot-1, strikes an imposing, almost patrician figure. On this February morning, he's dressed sharply in a gray pinstripe suit, stiff white shirt, and silk tie, his bald head shining above his round glasses. He doles out handshakes, smiles, and encouragement. "Nice job yesterday," he tells one senior.

His charter school, a former Catholic parish building he gutted and modernized, sits at 55th Street and Cedar Avenue, across from worn rowhouses. It opened in 2007 with 144 freshmen through open enrollment, and 100 more on the waiting list.

Every spring, freshmen are welcomed in an induction ceremony, and three adults must join their parent-led team. "That means," Hardy says, "if a student has a game, a play, a meet, that there's going to be an adult cheering for them. We can't have these guys doing all this work and they not be supported. Everyone has a responsibility."

The school has 450 students. The average freshman enters reading on a sixth-grade level. "We've had guys come in here reading as low as the second- or third-grade level," Hardy says.

He says that students who can't read or write don't succeed in college. Wages for men without a college degree are on the decline. "So when you have a male you graduate from your school who's not prepared for college, you've created a poor guy," he says.

"If these guys come to school and learn, they have a better shot to pay their bills, own a decent home, and have a better life."

To increase its offerings Boys' Latin relies on partnerships with mentoring programs such as Outward Bound. To enhance its curriculum, which includes a rowing team, a jazz band, a mock-trial club, a rock band called the Demerits, fencing, soccer, Web design, science labs, and a drama program, "I raise a lot of money," says Hardy, about $1 million in fiscal 2009, when he was paid $165,000 as CEO.

To boost reading scores, every student takes two English classes in ninth and 10th grade, composition and literature. For those who read below a sixth-grade level, "you don't get literature," Hardy says. "You get reading and reading instruction." Those below a fourth-grade level are assigned a reading instructor.

The attempt "has not been as successful as I'd like it to be," Hardy admits. "I'm not sure that we can be successful with guys reading on a second-grade level."

In classrooms across the city, black juniors lag academically behind their white classmates, and 11th-grade boys trail 11th-grade girls.

At Boys' Latin, almost 80 percent of the juniors cannot read at grade level, a failure Hardy traces to grade school.

"Somebody's going to have to go to hell for that," he says, "because the fact is, if you've been sitting there watching that - nobody said, 'Whoa! You can't read. Call your mom. Let's get everybody in here. Let's call out the dogs. We've got to do something to stop this.' "

A son of Philadelphia

Hardy, the youngest of four, grew up in the 1950s at 27th and York Streets, raised by his mother, a Veterans Administration clerk.

His teachers encouraged his mother to send him to a better school, outside the neighborhood. At Olney High, he studied Latin for two years. "I was an awful Latin student," he remembers. He found more success on the basketball court.

After college, Hardy bounced around. He returned to Philadelphia in 1986, to Logan Square, where he lives with his wife, and raised two sons, now in college.

Looking for something meaningful, he worked at a North Philadelphia private school as a substitute science teacher.

"I wasn't particularly that great of a science teacher," Hardy remembers. "In fact, I was probably only a chapter or two ahead of the kids."

The next semester Hardy taught English and math to middle schoolers, who stole his heart.

"I really connected with those kids," he says. Hardy felt he had control over their educational opportunities, "and that made me feel better about being able to be effective as a teacher."

In 2007, Hardy opened Boys' Latin. The school has its overachievers, those on academic probation, and those like Dominic Roher who show Hardy what's possible.

Roher had a reputation for fighting, talking back, and pulling D's. "I didn't know which way my son was going," said his mother, Barbara Crawford.

She admits Hardy's tough talk frayed her nerves. But Roher "took to Boys' Latin like he belongs there." A senior, he's on the honor roll and the baseball team and in the mock-trial club. He has been accepted at eight colleges and plans to study political science. "I'm a very proud mother," Crawford says.

By 9 o'clock, classes have settled in. In Room 107, seniors discuss Homer's Iliad. In a geometry class, a repeat student bites his pencil. Down a hall, a boy in a curly blond wig runs lines for The Tempest. Near Hardy's office, three boys prepare for the national Latin exam, four medals between them, reading Julius Caesar's Gallic Wars.

In the lobby, students wait for a chaperone to take them to Albright College, in Reading, for interviews.

"All you guys ready?" Hardy asks.

One boy looks pensive. "I'm nervous about the interview."

"Why?" Hardy asks, sizing him up before both break into laughter. "You nervous that they'll find out who you really are?"