Use vacant schools for housing for seniors, disabled

Mark Schwartz is executive director of Regional Housing Legal Services and board member of the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA)

Mark Schwartz

is executive director of Regional Housing Legal Services and board member of the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency (PHFA)

John Paone

is the president of Thomas Mill Associates, former executive director of the Philadelphia Housing Authority, and a PHFA board member

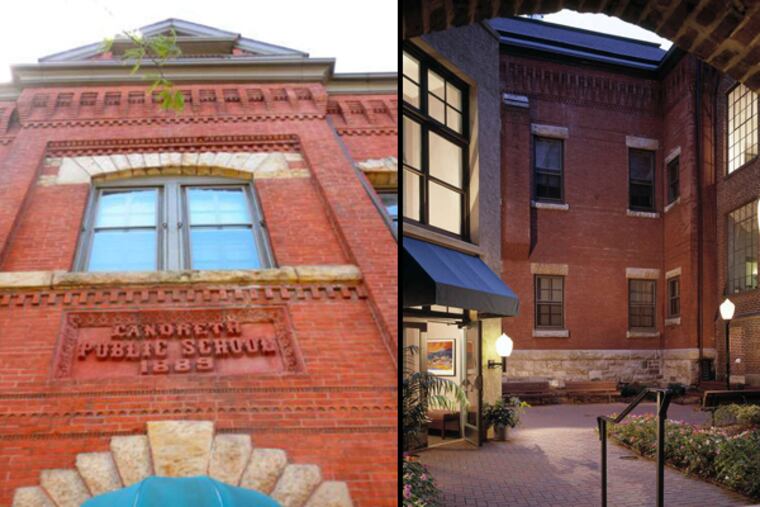

The closing of a neighborhood school, no matter how economically necessary or educationally defensible, is traumatic for students, their families, and the surrounding neighborhood. During the last school year, the School Reform Commission announced the closing of 24 schools in Philadelphia, and there likely will be more in the years to come. Vacant school buildings have the potential to become eyesores, safety hazards, and havens for dangerous or illegal activities.

Under the plan recently agreed to by Mayor Nutter and City Council, some of the buildings undoubtedly will be sold to developers, charter schools, or other buyers and put to productive use. Others - especially former elementary schools in struggling neighborhoods - simply do not have the same appeal. They may be too big, too old, or too dilapidated (the median age for school buildings up for sale in Philadelphia is 91 years), or they may lack the all-important quality of location-location-location.

What if these buildings and vacant buildings that once housed parochial schools could become safe, affordable housing for the city's growing senior population - some of them residents of those very neighborhoods - or for people with disabilities? The legislation to approve a second casino that is pending before City Council provides a unique opportunity to make that happen. It all has to do with tax credits.

For the most part, affordable housing developments in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania - in fact, across the nation - are financed through the federal Low Income Tax Credit program, which is administered through state agencies. In Philadelphia's case, that's the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency.

Known as "9 percent credits," affordable-housing subsidies attract private equity capital to finance construction or renovation of affordable housing. Without these tax credits, it would be difficult to get the kind of up-front funding necessary to build affordable housing. The "9 percent credits" have been very successful, but they are awarded competitively and are relatively scarce.

PHFA also administers another federal tax credit for housing, the "4 percent credit." It is more readily available, but not as popular with developers; it represents a bigger financial risk on their part and requires an infusion of funds to fill the gap between the value of the 4 percent and 9 percent credits. Currently, there are few sources of funding available to fill this gap.

The pending approval of one of six bidders for a second casino in Philadelphia offers a way to bridge that funding gap and make the 4 percent credit a much more viable funding alternative.

As a prerequisite for granting a license to the new casino, City Council should require the winning bidder to make an annual contribution to the Philadelphia Housing Trust Fund for 10 years. The guaranteed income would allow the fund to borrow to provide the needed cash to make the 4 percent credit more workable for nonprofit and for-profit developers. Those contributions could also be matched by an increase in the filing fees, which currently provide the source of funding for the Trust Fund, and then combined with the 4 percent credit. (The same requirement would, of course, be extended to the currently operating SugarHouse Casino.)

This money, administered by the Trust Fund, would be restricted to renovating vacant school buildings and lent to developers consistent with the requirements of the 4 percent credit.

This is a creative approach that takes advantage of an underutilized resource to deal with an immediate crisis. Now-vacant school buildings once were the centers of their neighborhoods. If they can be renovated and reused, they could help revitalize the surrounding areas.

More important, they could provide the affordable homes that seniors and people with disabilities so desperately need.