Windfall for Phila. principals short on supplies

When he became principal of Lingelbach School this year, Marc Gosselin was stunned to learn that the 374-student school's budget for supplies this year was a meager $160.

When he became principal of Lingelbach School this year, Marc Gosselin was stunned to learn that the 374-student school's budget for supplies this year was a meager $160.

"As a new principal, I couldn't even send a letter to parents introducing myself," he said, "because I couldn't buy stamps."

On Tuesday, Gosselin and other principals around the district learned that his school was in line for a cash infusion - and right away - as a result of the district's decision Monday to cancel the teachers union contract and require teachers to pay more toward their health insurance.

Although teachers won't be forced to make contributions until Dec. 15, the district, said spokesman Fernando Gallard, has $15 million to spread around in anticipation of savings.

Under the plan, schools deemed most in need will get $125 per pupil, and the rest, including the district's magnet schools, will get $100 per pupil. For Lingelbach, that means an extra $46,625.

"It sounds like a lot of money, but it gets used up extremely quickly," Gosselin said. "We're so far away from being at the normal operating level of a school, we're just trying to get up to what a normal school needs to function."

The district intends to distribute another $15 million to the schools in January or February and $13.8 million in April, Gallard said.

For principals who have been struggling to run their schools on bare-bones budgets, the news brought mixed reaction. They're getting financial aid, but at the expense of their teachers, many of whom have been volunteering extra time and buying supplies out of their own pockets.

"I can't say that they're necessarily happy," said Rob McGrogan, head of the Commonwealth Association of School Administrators, the principals' union. "They see modest financial relief as a direct result of something that brings them professional and personal conflict."

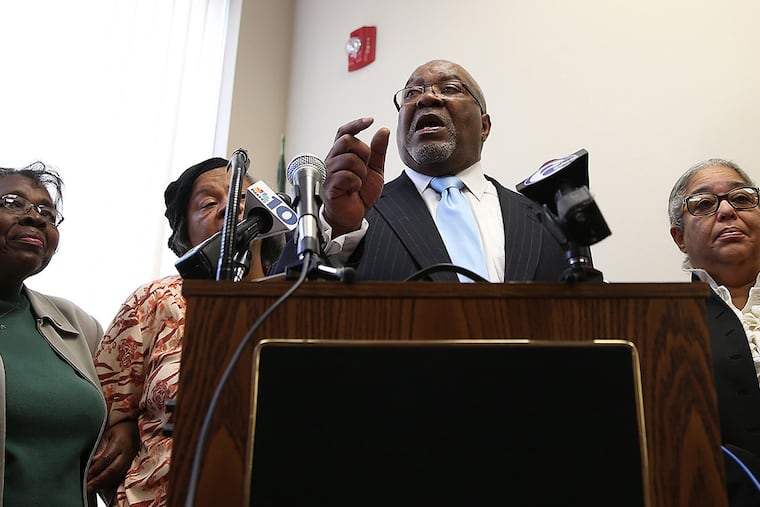

But Philadelphia Superintendent William R. Hite Jr., speaking at a Philadelphia Bar Association gathering Thursday, defended the district's decision to cancel the contract as unavoidable, saying schools could not wait any longer for much-needed financial aid.

"It's important," he said, "because our children can't go through another year like they did last year."

Among those in the audience were two former School Reform Commission members, Pedro Ramos and Michael Masch. Ramos, a lawyer, sat in the back and declined to comment after the session, saying he attended merely as an "interested citizen."

Masch, who was invited by Bar Association Chancellor William P. Fedullo, came with a three-page statement and charts, blasting the state as failing to fund the School District adequately.

"The time is past due for Philadelphia to stand up for itself and demand fair treatment in Harrisburg," said Masch, who was state budget secretary under Gov. Ed Rendell and is a former chief financial officer of the School District, in addition to having served on the SRC. "It is time to draw the line - no further increases in local taxes, no further cuts in school budgets, no further labor concessions. . . ."

Masch, now vice president and chief financial officer at Manhattan College, said that he supported requiring teachers to pay toward health insurance, but that they also should be paid comparably to their suburban counterparts.

The 11,500-member teachers union and the School District have been in contract negotiations for nearly two years, meeting more than 100 times. The union has vowed to fight in court the district's cancellation of its contract, and Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, will travel Friday to Greenfield School to meet privately with Philadelphia Federation of Teachers president Jerry Jordan, City Council members, state legislators, and community leaders.

Hite said the district would continue to bargain with teachers in hope of reaching an agreement. There were no sessions this week.

Principals, meanwhile, have been asked to meet with their teaching staffs to decide how to spend the first round of money. The district issued broad guidelines on what schools could buy - everything from teachers to staff training and supplies, technology, counseling, and tutoring.

"We certainly have lots of needs," said Patricia Cruice, principal of Dobson, a K-8 school in Manayunk with about 300 students. "We have a great need in technology."

She plans to meet with her leadership team to set priorities.

Lisa Ciaranca Kaplan, principal of Andrew Jackson School in South Philadelphia, said that she needed a full-time guidance counselor most, but that the $50,000 or so she was to get would not be enough to afford that.

"If they were giving me hundreds of thousands of dollars," she said, "maybe we could do something."

She learned she may lose a teaching position through leveling, the annual practice in which the district redistributes teachers in October, depending on enrollment shifts. If that happens, she said, she would have to use the money to fill that gap.

At Lingelbach, Gosselin said he would use the new funding to improve reading scores, among other areas. The school, he said, also wants batteries for laptops, bulbs for overhead projectors, technology, and textbooks.

Gosselin came to Philadelphia this year from the Stroudsburg Area School District. Here, he bought his own desk for his office and said he was shocked to see the difference in the level of resources between the two systems.

"It was a whole different world," he said. "In Stroudsburg, we had a custodial staff that worked around the clock. When I came here, there are years of neglect that is very visible."

215-854-4693 @ssnyderinq