In cash-strapped School District, a hidden treasure trove of books

The teacher had heard about the books. Thousands and thousands of them, from two dozen city schools shuttered two years ago. Perfectly usable. All sitting boxed up and unused in the basement of the Philadelphia School District's headquarters.

The teacher had heard about the books.

Thousands and thousands of them, from two dozen city schools shuttered two years ago. Perfectly usable. All sitting boxed up and unused in the basement of the Philadelphia School District's headquarters.

Like so many city teachers, she uses fund-raising websites to get the books she needs for her students.

Like so many city teachers, she has students who can't bring home their torn-up textbooks because there aren't enough to go around.

If there were books, the teacher wanted some.

What she saw in the dusty basement of the School District building left her flabbergasted.

A city block of books. Some of them shrink-wrapped. Some of them dumped in boxes. Some stacked on the floor. Few labeled. Nothing organized. Kindergarten readers next to high school books. Expensive Storytown reading series, gathering dust. Science, algebra, literature textbooks. Literary kits and phonics sets. Books for English-language learners.

Classics like Jack London and Mark Twain. The Hardy Boys. Nancy Drew.

This is a travesty, she thought.

She had one simple question: "Why aren't these in the hands of Philadelphia children?"

Great question, Teach.

But she didn't know the half of it.

There are thousands more unused books - and other things city kids badly need, including pianos and other instruments - piled up in the hallways and classrooms of the shuttered Bok High School in South Philadelphia.

The books were dumped there two years ago when Bok and 23 other schools were closed. They've just been sitting there since.

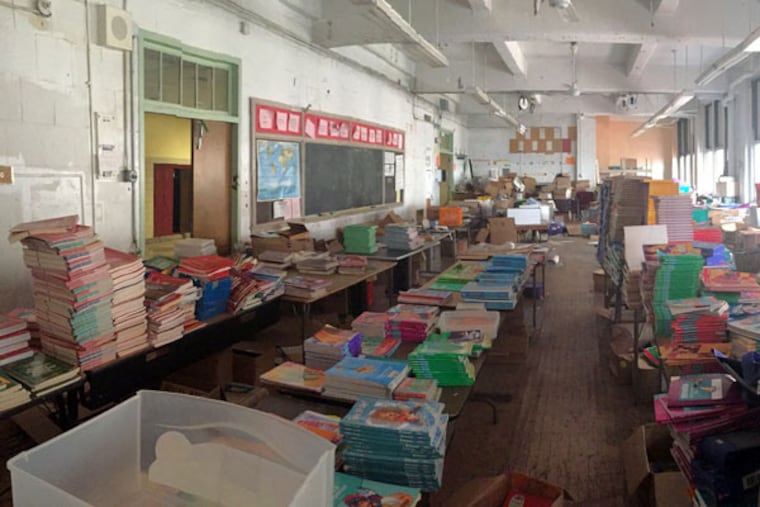

If things are messy in the district basement, Bok is worse.

At Bok, it looks like the district ran out without paying the rent and left behind all the books.

The hallways are crowded with boxes and boxes and boxes of books.

Thousands of early readers: The Popcorn Shop. The Marble Patch. Clifford the Big Red Dog.

Tables and tables of young adult novels. History books on Winston Churchill and Wilma Rudolph.

For high schoolers, Thomas Hardy and more Twain. Jane Eyre. Macbeth. Our Town.

In the classrooms, stacks of textbooks lean like skyscrapers. Some date back to 2000. Others were last used in 2013. Many look like they were never cracked open.

Forget about the science books under that leaky fourth-floor ceiling - they're no good anymore. Other books sit under a sign marked, "shred."

In a district where almost 60 percent of the kids cannot read at grade level, the library is heartbreaking. Many shelves are still stocked. There are hundreds of dictionaries.

And the marching band equipment, pushed into a corner of the library: Five pianos. Bass drums. Kick drums. Trombones. The green-and-white band uniforms lie on the floor like the empty cloak of the Wicked Witch of the West.

In a broke district, there's no music program that could use that stuff?

In a district where advocates estimate that a third of the kids have no books at home, is anyone trying to catalog this stuff? If some textbooks are outdated, couldn't they be sold or traded out for the tattered texts teachers are embarrassed to hand out?

Why don't more teachers know about them? And those novels, why aren't they in the hands of kids who could get lost in their pages?

When I talked with district spokesman Fernando Gallard on Tuesday, he offered bureaucratic explanations that indicated this is not a new problem.

Much of the material in the district basement, he said, were from outdated curricula taught during the administrations of Superintendents Paul Vallas and Arlene Ackerman.

If that's the case, how many thousands of dollars in waste is lying around there?

And in a district in financial crisis, aren't old textbooks better than no textbooks?

Math doesn't change. Chemistry doesn't change. Literature is timeless.

Gallard said principals and teachers have an open invitation to come to the basement to look for what they want.

"We are slowly but surely finding new homes for the materials that can be used," he said.

As for the thousands of books at Bok, that's different, he said.

With all the cuts in recent years - more than 5,000 employees in three years - the district lacks the resources to go through all the materials warehoused there.

The teacher who had to go and have a look for herself said that if more teachers knew, they would surely volunteer to get the materials sorted.

That's not going to work, Gallard said. It's too big a job, he said.

So instead the district is bringing in an outside company to audit the material at Bok. A broke district is paying someone to tell it what books it already has.

And it's not going to happen overnight.

"It's a time-consuming process," he said. "We're doing it as quickly as we can."

The teachers' union had no idea about all the unused books.

"It's unconscionable," said Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. "How did his happen? How could it happen?"

Excellent questions.

Bureaucratic answers are not enough.

This is simple. There is a big building with lots of books. And there are lots of children without books. Go and get the books and give them to the children.

Now.

215-854-2759 @MikeNewall