March Madness -- in the physics lab

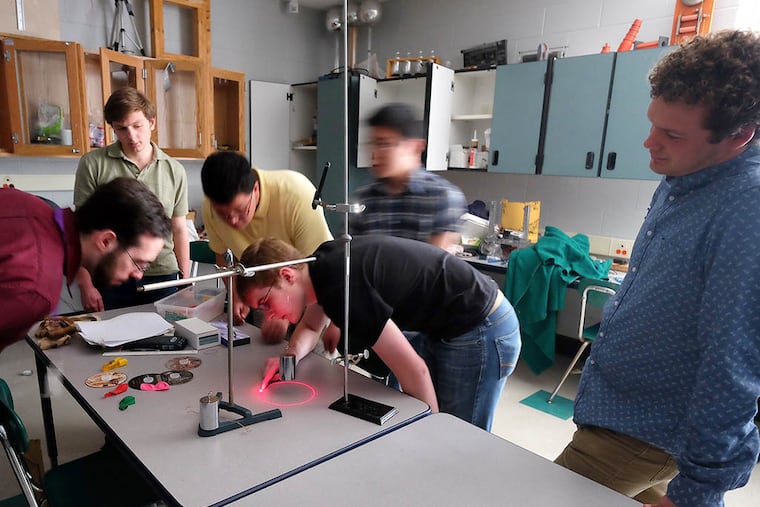

It was not your typical March Madness for the competitors who were vying to become the Final Five. The fans inside the Chester County high school weren't crowded around a basketball court, but around lab tables. The only hoops the kids had to jump through were metaphoric: the pressure of defending scientific theories during sharp questioning from physics experts.

It was not your typical March Madness for the competitors who were vying to become the Final Five.

The fans inside the Chester County high school weren't crowded around a basketball court, but around lab tables. The only hoops the kids had to jump through were metaphoric: the pressure of defending scientific theories during sharp questioning from physics experts.

Success meant a trip of a lifetime to Thailand this summer.

The students, who in June will become the first U.S. team in eight years to take part in the prestigious International Young Physicists Tournament, aren't from any upscale private academy - they're just hardworking kids from Phoenixville Area High School.

It's an underdog saga, a test-tube variation on the classic basketball film Hoosiers.

"I think it would be very presumptuous of us, one public school in Pennsylvania, to think that we could go there and win," said Jay Jennings, the physics teacher who organized the effort. "But I'm still confident enough to think realistically we could make the top half."

A truly Olympian task now awaits them in the Thai city of Nakhon Ratchasima. They'll compete against the best budding scientists from Singapore, Korea, and other nations where students typically start learning physics at an age when U.S. kids are taking the training wheels off their bikes.

"I think we have some obstacles," said Jennings, who didn't even know the tournament existed until a year ago when a casual contact on Twitter encouraged him to form a team. "We don't even require physics. In a lot of these countries, physics is the primary science that they learn."

Many countries hold regional contests to find the very best students, and many train during class. In Phoenixville, the kids work after school and weekends, putting in as many as 30 hours a week, all while juggling sports, band, Model U.N., and multiple Advanced Placement courses.

They want to disprove the stereotype that U.S. students have lost their way in science and math. The international Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, in 2012 ranked the United States 27th out of 65 nations for science skills among 15-year-olds.

In Europe, "if you don't have three or four years of physics," you can't be considered a physics "nerd," said Don Franklin, a former coach of American teams at the international tournament who is helping Phoenixville prepare.

Still, U.S. teams, consisting of students from private academies such as the Rye Country Day School in affluent Westchester County, N.Y., tied for second place with Belarus in 2005.

"We know the United States is sometimes perceived as being arrogant" and the students "full of themselves . . . but it's to their advantage that they don't get rattled," Jennings said of his squad.

It also helps that the competition is conducted in English. When the United States stopped sending a team after 2007, it was because of a dispute over rules: U.S. officials wanted fewer questions and changes in judging. When tournament officials refused, the nation stopped participating.

But Jennings said he became "hooked" after watching an online video of a "physics fight" between teams.

To prepare, students spend all year researching 17 projects. At the competition, three teams debate a project: the presenter; a challenger, which asks the first team to solve a problem in 12 minutes and debates the answer; and a review team, which along with the judges asks questions. After one hour, the teams reverse roles.

The 31 competing nations are whittled to three finalists, and after a last debate, the winner is selected.

Earlier this year, Phoenixville got a taste of what's to come when it competed - with five different students - at a smaller, U.S.-based competition, and beat former champions from China. Although they came in sixth out of nine, the Phoenixville students did so well that they were accused of using a college professor's work. Jennings said he vouched for his students.

Karl Sewick, 17, one of the Thai-bound students who wrote the code that was questioned at that competition, said beating the Chinese was a huge confidence boost.

"It was surprising," said the University of Pittsburgh-bound senior, who plans to study mechanical engineering.

Some of this year's physics quandaries include the science of tightly packing objects in a box; investigating the factors - such as walking speed or the shape of a cup - that might cause a person to spill coffee while walking; and making a glider from the bottoms of two light cups with an elastic band.

The challenges are fun for students who like to tinker, such as 17-year-old John Lukowski, who began taking apart remote-control cars in middle school. "I made a remote control for one from a TV remote," he said.

Elia Eschenazi, who chairs the department of mathematics, physics, and statistics at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia and has been helping the team, said the problems would challenge even college undergrads. He was a judge picking the team.

"We were asking very tough questions," he said, adding: "I think these kids can compete. They are all extremely bright."

Most of the students are planning careers in science. Andrew Mangabat, 17, plans to study mechanical engineering at Elizabethtown College. Brian Tu, 18, who also wants to study mechanical or computer engineering, said he's focused for now on this "rare opportunity."

David Mascari, 18, plans to major in neuroscience and said he's looking forward to "talking to the brightest students from other countries" at the tournament.

Right now, Jennings is focused on a math problem: making the dollars add up so he can get his team to Nakhon Ratchasima. Travel and equipment will cost $35,000; so far he and the students have raised about $15,000. They have a GoFundMe site and will be demonstrating their projects along with University of the Sciences at the Philadelphia Science Festival on May 2.

The team has much work left to do, but Jennings said his students have mastered a very important skill. Under intense questioning from judges, "they were so poised," he said, "and they had never done anything like that before."