Bryn Mawr confronts racist views of former leader

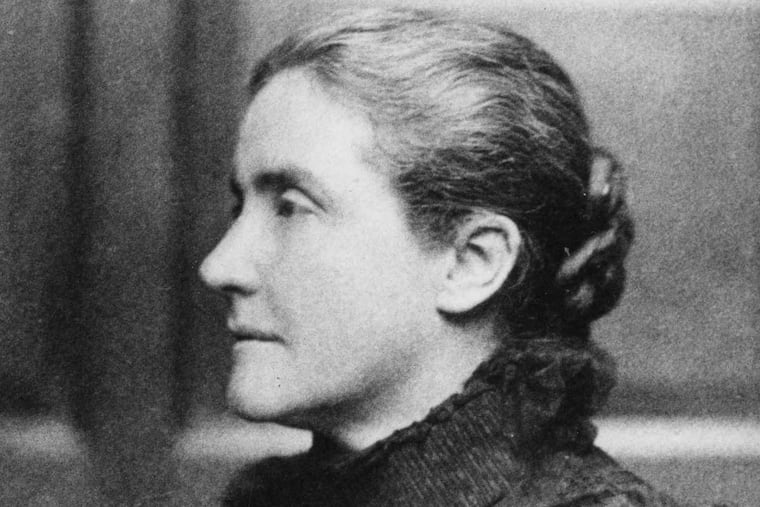

Bryn Mawr will no longer refer in printed materials or on its web site to its main gathering space as "Thomas Great Hall" or the building that houses it as Thomas Library. The move comes as the school looks at the complicated legacy of suffragist M. Carey Thomas.

Stirred by the fallout from the deadly Charlottesville protest, Bryn Mawr College this week took steps to distance itself from M. Carey Thomas, a leading suffragist and perhaps the school's most influential president, citing her racist and anti-Semitic views.

The college will no longer refer in printed materials or on its website to its main gathering space as Thomas Great Hall or the building that houses it as Thomas Library, president Kim Cassidy said in a letter to the campus community.

"While Thomas had a profound impact on opportunities for women in higher education, on the academic development and identity of Bryn Mawr, and on the physical plan of the campus, she also openly and vigorously advanced racism and anti-Semitism as part of her vision of the college," Cassidy said.

The issue has been brewing for a couple of years and over the last few months, a campus committee of faculty, students, staff, trustees, and alumnae has been debating how to handle the legacy of Thomas, who led the college from 1894 to 1922.

But Cassidy said that given the violent uproar over white supremacy demonstrators in Charlottesville this month, mounting concerns about racism, and "an especially raw moment for members of many different marginalized groups whose rights and dignities are being attacked so openly and so viciously," she thought it was prudent to issue a moratorium on the use of Thomas' name for 2017-18 while the committee completes its work.

"We will make a concerted effort to remove as many references to the name as is possible for this year," she said.

When or if the block-lettered name that hangs over the entry to the building will come off hasn't been decided, Bryn Mawr spokesman Matt Gray said.

The Main Line women's college is the latest school to deal with the complicated legacies of former leaders whose buildings bear their names. Princeton University last year after much debate and controversy decided to keep the name of Woodrow Wilson, former U.S. and university president, on its School of Public and International Affairs.

The issue also comes as campuses across the country are bracing for more controversy in the wake of the violence that started with a white nationalist march through the University of Virginia campus this month and erupted the next day elsewhere in Charlottesville at a rally, where a woman opposing white supremacy was killed.

Pennsylvania State University this week banned white nationalist Richard Spencer — who had been scheduled to appear at the Charlottesville rally — from speaking on campus this fall. Calling Spencer's views "abhorrent," Penn State president Eric Barron said: "There is no place for hatred, bigotry or racism in our society and on our campuses."

Several other colleges, including Texas A&M University, the University of Florida, and Michigan State University, also have banned appearances by Spencer.

Cassidy, too, referred to Charlottesville in her letter, calling what happened there "profoundly disturbing."

"The views and actions of neo-Nazis, the KKK, and white supremacist and xenophobic groups are antithetical to the values we strive to embrace at Bryn Mawr," she said.

Bryn Mawr's campus is diverse: About a third of its 1,381 undergraduate students are Hispanic, black, or Asian, and that doesn't include the college's significant international population. Founded in 1885, the campus is largely liberal.

Conversation over Thomas proved complicated. The former college president figured prominently in helping women achieve equal rights. For a time, she led the National College Women's Equal Suffrage League, and Bryn Mawr under her leadership served as a hub for the suffrage movement, according to a special collection in the college library. Thomas brought prominent women's rights activists, including Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt, to campus to speak.

But like some other suffragists, she was focused on expanding rights for white, privileged women. She was reluctant to admit black students to Bryn Mawr and also rebuffed the hiring of Jewish faculty. Her views were illuminated in the 1994 biography, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas, by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, an emerita professor of history and American studies at Smith College.

Debate about the legacy of Thomas, who died in 1935, has been going on for more than a decade. A written summary of "a noon conversation" on campus in 2005 included discussion about correspondence from Thomas in which she indicated black students may not feel comfortable at Bryn Mawr.

"The question has never come up at Bryn Mawr College as to whether it would be possible to admit a student of the negro race, and it is the policy of the college not to decide a general question until a specific case is presented," Thomas wrote in a 1906 letter. "As I believe that a great part of the benefit of a college education is derived from intimate association with other students of the same age interested in the same intellectual pursuits, I should be inclined to advise such a student to seek admission to a college situated in one of the New England states where she would not be so apt to be deprived of this intellectual companionship because of the different composition of the student body. At Bryn Mawr College we have a large number of students coming from the Middle and Southern states so that conditions here would be much more unfavorable."

In her comments to the freshman class in 1916, she said: "If the present intellectual supremacy of the white races is maintained, as I hope that it will be for centuries to come, I believe that it will be because they are the only races that have seriously begun to educate their women."

In several letters, Thomas made anti-Semitic remarks, including a comment on her desire to have a faculty made up of "our own good Anglo-Saxon stock."

While Thomas claimed that African American students did not apply to Bryn Mawr during her tenure as president, she diverted Jessie Redmon Fauset, an African American student who received a scholarship to attend Bryn Mawr in 1901, to Cornell University, and helped pay a portion of Fauset's tuition.

Horowitz, the author of the book on Thomas, said she was "conflicted" about the college's decision to move away from Thomas.

"You're looking at a deeply flawed person," she said, "but also one with a very powerful vision of women, who was opening doors at least for some women."

She said colleges would do better to understand the deep flaws in their history and work to reshape them rather taking symbolic actions such as removing names.

As the recent debate over Thomas' legacy ensued, a student petition called for her name to be removed.

Bryn Mawr alumnae and others connected with the school posted their views on social media sites, including a private Facebook page for alumnae and the Twitter hashtag #bmcbanter.

"The Power & Passion of M. Carey Thomas is on the @Wellesley College library free books shelf & I think I have to rescue it," tweeted former Bryn Mawr College scholar Monica L. Mercado.

"Great hall!!!" tweeted another.

"I am in literal shock," said a third.

Michelle Lee, a 2015 Bryn Mawr graduate, applauded Cassidy's decision.

"I'm pretty proud that Bryn Mawr is taking steps to remove and kind of reconcile with the actual racist past," said Lee, who works as a brand strategist at a media company in New York City.

Cassidy has asked that the committee reviewing Thomas' legacy come back with recommendations in the spring.

This article has been updated to amend a quote from Thomas regarding admittance of African American students to the school.