'War' springs from the page

The War, the companion volume to the Ken Burns documentary, looks, at first glance, like the coffee-table book of the season. It is, but only in the sense that, given its size, a coffee table might be the most practical place to read it. And The War should be read by everyone in the family, from the high schoolers, many of whom, as Burns points out in his introduction, "think we fought with the Germans against the Russians in the Second World War," to the baby boomers, who think they know what their parents went through.

nolead begins An Intimate History, 1941-1945

nolead ends nolead begins By Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns

Knopf. 480 pp. with 394 illustrations and 21 maps. $50

nolead ends nolead begins

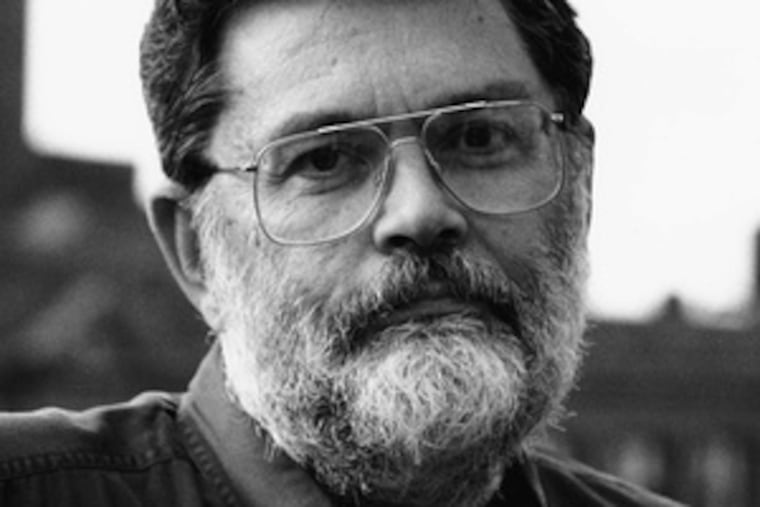

Reviewed by Allen Barra

For The Inquirer

nolead ends The War, the companion volume to the Ken Burns documentary, looks, at first glance, like the coffee-table book of the season. It is, but only in the sense that, given its size, a coffee table might be the most practical place to read it. And The War should be read by everyone in the family, from the high schoolers, many of whom, as Burns points out in his introduction, "think we fought with the Germans against the Russians in the Second World War," to the baby boomers, who think they know what their parents went through.

Unique not only among previous volumes that have accompanied Burns' documentaries but also among just about all books on World War II, The War's text pursues two main currents: the stories of four American towns during the war years and the bigger picture of both the European and Pacific fronts. The course of the war is never allowed to become too distant a subject; when the battles are linked to the lives of the men who served and their friends and family in Waterbury, Conn., Mobile, Ala., Luverne, Minn., and Sacramento, Calif., history becomes the stuff of personal drama.

Geoffrey C. Ward, prize-winning biographer of Franklin Roosevelt and author of the books for three other Ken Burns films, including The Civil War, handles the historical narrative deftly. What, one wonders, is left to say about this war? The answer is not so much new information as new interpretation.

Ward is tougher than almost any recent historian on the generals and war planners whose decisions were responsible for such massive blunders as the feeble defense of the Philippines in 1942 and the landing at Anzio in Italy in 1944. And the reader will be, too, when men we have come to know die needlessly.

Ward juxtaposes major events with illuminating details. (In Mobile, for instance, both country music legend Hank Williams and the father of home run hero Hank Aaron worked in the same shipyard, the kind of integration that would not have happened if not for the war effort.) But it's the personal side of the book that is most telling, the stories of the common people from these towns and many others, including Japanese Americans who went off to fight the Nazis while their parents lived behind barbed wire in internment camps.

Their stories are told through newspaper articles, old photographs, letters to and from the fronts, and, sometimes most heartrending of all, home movies that family members have kept for more than 60 years. They are also told, in many instances, by the participants themselves.

Everything serves to re-create a time when Americans got their war news from the morning papers and radio rather than television and the Internet. We find out the fate of the soldiers, sailors and airmen as their loved ones find out. Each new death (usually conveyed via a Western Union telegram; the reproduction of one provides one of the book's starkest photos) hits the reader with the jolt of an emotional rifle slug.

Part history, part memoir, and part photo album, The War is compelling on many levels. The photographs are a mesmerizing collection of both the war the GIs saw and the changing world they left behind. Many are so upsetting that for a long time they were known only to the men who took them. In the Ardennes Forest, American soldiers tried to distinguish between their own dead and the enemy in a pile of frozen corpses; in Dresden, a German city destroyed by Allied bombs, the dead - men, women and children - are heaped in piles more than six feet high; Marines on Okinawa standing around a radio look stricken as they hear the news that the war in Europe is over - when will their war be over?

Much of The War will hit the uninitiated with a shock; readers will at least begin to understand why fighter pilot Quentin Aanenson could never return to his father's farm in Minnesota. "I find there are times when I'm pulled back into the whirlpool," he says. "The intensity of that experience was so overwhelming that you can't let go of it."