Jorge Cousineau, Philadelphia's theater magician

A tall, lanky guy spends long nights, sometimes past dawn, in the half-room he calls his workshop at his Northern Liberties home. He manipulates sound and light, gadgets and images, reality and illusion. Then he brings his effects, his video tricks and electronic magic, into a theater and takes your breath away.

A tall, lanky guy spends long nights, sometimes past dawn, in the half-room he calls his workshop at his Northern Liberties home. He manipulates sound and light, gadgets and images, reality and illusion. Then he brings his effects, his video tricks and electronic magic, into a theater and takes your breath away.

His name is Jorge Cousineau (YORG KOO-zin-oh), and during a typical Philadelphia theater season he might be listed in programs for a dozen shows or more.

Cousineau has filled a set with recorded projections on large screens so that real actors could walk in and out of their virtual selves (New Paradise Laboratories' Fatebook). He has provided a rainy, tearful soundscape to suggest the interior rhythm of an entire play (Theatre Exile's Shining City); created three-screen video and sound design that transformed a live spoof of current events into a mixed-media delight (1812 Productions' This Is the Week That Is); splashed a stage floor with mesmerizing, moving geometrical patterns that set a precise mood between scenes (the Wilma Theater's Language Rooms).

For a family show called If You Give a Mouse a Cookie, now at the Arden Theatre, he installed video into a mirror that makes it misbehave to such a degree that one kid in the audience cried out, "That mirror is cwazy!"

All the above is cwazy to anyone who can't figure out how it might be done, let alone conceived. And all the above has appeared here in just this season.

Several Philadelphia theater artists make at least part of their livelihoods creating special effects for the stage, but Cousineau, 39, is inarguably the regional stage's master wizard.

A native of Dresden, Germany, who as an art student rejected set design as uninteresting then later turned to it professionally, Cousineau has taken on so many aspects of stagecraft that he's hard to classify. He works variously as a video designer, sound designer, composer of music, production designer, and a general inventor of effects; for some shows, he is bits and pieces of all of these.

"I don't draw lines," Cousineau says. "I like very much not to live in one category." Pressed, he offers "self-employed freelance theatrical designer," which is far too vague to capture what he actually does.

"When you get Jorge, you get the complete package," says Theatre Exile's producing artistic director, Joe Canuso, who has worked with Cousineau several times and will again next season. "He's a great collaborator because he can see all the different elements and how they fit together so well. He just has a great vision. He's an amazing, unique talent."

Cousineau's latest work is in the Arden's new production of Stephen Sondheim's musical Sunday in the Park With George, in previews and opening Wednesday.

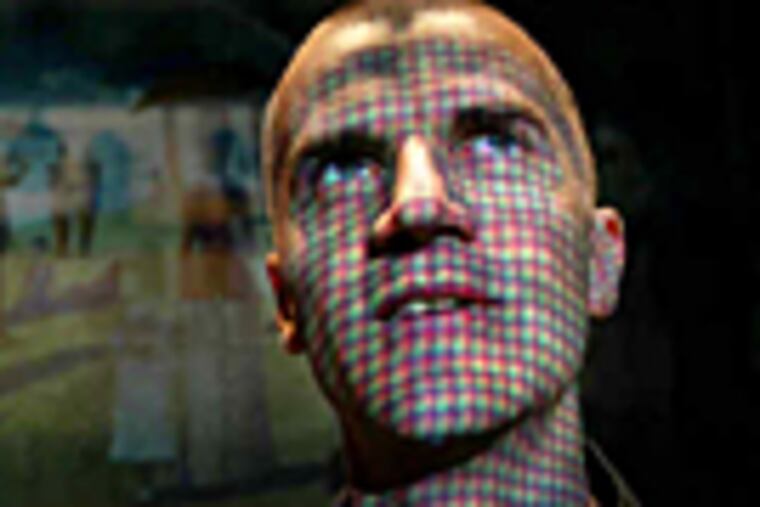

The show examines the thoughts of impressionist artist Georges Seurat as he composes his 1884 masterpiece, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, then explores the way the artist's great-grandson struggles a century later. It boasts some of Sondheim's most challenging music and lyrics - spare and elegant, patterned on Seurat's pointillism. The book for the show is by James Lapine.

This is the Arden's - and its director, Terrence J. Nolen's - second go-round with Sunday in the Park; it comes 16 years after the first, in a much more graphically rich era for the stage.

Special-effects designers who worked in theater were once pretty much confined to Broadway, and what they could accomplish in a pre-digital/MP3 age does not compare with today's possibilities.

Sunday in the Park, a show about art both old and new that uses its actors to stand in for Seurat's painted characters in a now-famous tableau, almost begs for graphics to make it more accessible. Two years ago on Broadway, a super-high-tech revival wowed audiences to the extent that some people called the effects the star of the show - a dynamic that Cousineau and Nolen say they have worked hard to avoid.

Knowing that Sunday in the Park was a future Arden production, neither man saw the revival. "I just didn't want it necessarily in my mind," says Nolen. And Cousineau stresses that he's careful about effects that may steal, rather than contribute to, theatrical thunder, always aware that his work must be in balance with the production.

Balance, indeed, is what Sunday in the Park is about, and is part of Seurat's mantra about the elements that make art: balance, order, design, composition, tension, light, and harmony.

Those same elements guide Cousineau's work in general, and help make it memorable. He is close to other designers in productions and soaks up the director's vision, he says. And, not infrequently, he abandons ideas.

"There's always something that cannot be done. Actually, that's a good thing. Often the limitations of time and money lead to a better balance of what is being said and how you say it."

Sometimes, balance may call for extremes - as in the Christmastime pantos People's Light & Theatre Company has come to own. Says actor-director Peter Pryor, who had Cousineau on board when he staged the pantos Cinderella and Snow White: "We would meet for coffee at various times and come up with crazy ideas and Jorge would tell me what he could do - and come up with something crazier."

Cousineau is a constant at the Arden, now immersed in his 40th show there.

"Jorge has become one of my favorite collaborators," says Nolen, Arden's producing artistic director. "We started with Jorge doing sound and in part, through this relationship, our use of sound has grown so much. Then he started us using video in a much more expanded way."

Indeed, Cousineau's sound design for an Arden world premiere, local playwright Michael Hollinger's Opus, won him a Lortel Award in 2008 for its off-Broadway production, and is now licensed whenever that play is produced.

For Sunday in the Park, Cousineau's design - the logistics appear on his complex sound and video "plots," as they're called, like road maps aliens might use - calls for nine video projectors and 13 speakers, the most the Arden has ever used. Developing that scheme is the sort of thing that envelops him, he says, going back to art-school days. "The finished version of a painting was always less interesting to me than the process I was going through."

He was still in college, a DJ who produced for bands, a student obsessed with motion in time, and a gallery artist staging an event with four slide projectors in 1994, when he attended a touring dance performance by Philadelphia's Group Motion Dance Company. "I was blown away by the dancing," he says.

And also by one of the dancers, Niki Cousineau, the dancer-chorographer whom he eventually married and whose surname he adopted. They have two children and run the dance company Subcircle. Niki Cousineau is Sunday in the Park's choreographer.

Cousineau came to Philadelphia in 1996 after Manfred Fischbeck, one of Group Motion's founders, heard soundtracks he'd put together and invited him to be the group's sound designer. Visas were a problem - he had to return to Germany, where Niki married him, and stayed behind for nine months until he was allowed back.

His work was noticed by theater producers here, and Cousineau began his long relationship with many of them, learning new tricks as he moved from stage to stage.

"I'm still learning," he says of all the different digital fields he tends. "Each field develops exponentially faster than it ever has. It's hard to keep up with all of it."